Animals are all around us; as I write this, stinkbugs are crawling on my office window, squirrels are busy in the white pines and poplar trees, and (though I can’t see them) deer and bobcats are roaming not far away. Culture usually trains us to draw sharp lines between ourselves and all other species. We also differentiate those species we choose to live with (cats, dogs, chickens) from those we term “wild.”

But I’m fascinated by the places where those categories break down. Are the mice who intrude on my cupboards wild? Is my cat wild when he hunts a songbird? Are the songbirds becoming domesticated if I feed them suet? What about the microorganisms that make up much of our body mass?

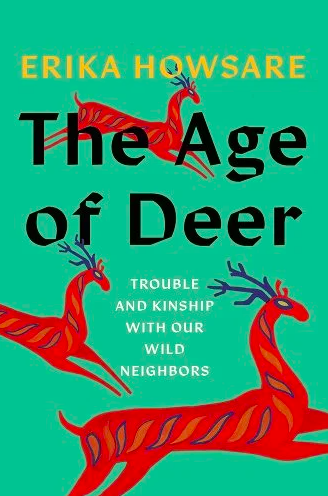

Writing my book, The Age of Deer, was a deep dive into those kinds of questions, prompted by the long and tangled history humans share with deer. We’ve influenced each other so profoundly—ecologically, biologically, culturally—that the more I researched our relationship, the more the conventional lines of division between us began to seem blurry at best. Here are eight other books that examine the interconnections among humans and some of the species—or “nations,” as they’re sometimes called—with whom we share the Earth.

Winter: Effulgences & Devotions by Sarah Vap

Centered on the Olympic Peninsula, Vap’s recursive, questing book-length poem charts a radical porousness between people and whales, salmon, microorganisms: all the species that are part of our world, that influence us and are influenced (and devastated) by us. But the dissolving boundaries in this book also include those between Vap and her children and husband—the “family animal,” in her phrase, a collective organism that sleeps, eats, nurses, plays, shares thought and speech, seeps in and out of the language of the writing. The project took years to write and contains many layers of personal history and political response, but it constantly circles back to the image of a mother who is as vulnerable to the beloved interruptions of her young sons as she is to the horrors of climate change, extinction and war. The body here becomes a hinge between human and animal existence, a reminder of our inescapable (and why would we want to?) creaturehood.

Milk Tongue by Irène Mathieu

Animal life is not the overt focus of this book, but in and amongst Mathieu’s explorations of history, family, and her work as a pediatrician, wildlife is a quiet and frequent presence, inviting itself into the human world. Thrush, an infection of the mouth, is also a bird that “lands on the windowsill” and becomes woven into a complex imagistic fabric. Deer tracks are the epicenter of “a kind of country… we drew.” Mathieu’s poetry finds slippages between body and landscape, brain and culture, and locates moments when the domesticated world collides with the feral (a moth, having strayed into a kitchen, cut down by a snapped dishtowel) and those when the human is drawn forward and outward by the more-than-human: “confused animal I am,” she writes, comparing herself to “the small miracle of organization” represented by a flock of geese.

When Women Were Birds: Fifty-Four Variations on Voice by Terry Tempest Williams

Birds in this book are messengers carrying mystical resonances, like the ruby-throated hummingbird who hovers in front of Williams as she kneels on the ground, grieving a friend. Or the owl who appears, seeming to warn her, as she follows a dangerous man into the wilderness, against her own better judgment. Her world is vibrant and full of signs, and she possesses deep recall of many moments from across her life, like a sunrise she watched with her grandmother in the Uinta Mountains of Utah, when they witnessed a golden eagle silence the dawn chorus of songbirds and grab a mouse. “Voice” here means authentic speech, speaking up or out, and birds are Williams’ guides through a life in art, activism, and family.

Yaqui Deer Songs / Maso Bwikam: A Native American Poetry by Larry Evers and Felipe S. Molina

Technically, this is an academic work of anthropology. From the first, though, it reads like a poem— fitting, since it brings forth the elegant, living body of literature created by Yaqui people in Arizona and Sonora. Yaqui deer dancers perform in order to invoke another world, the sea ania or flower world, from which deer emerge: mythic figures and key providers for humans. But it’s not as simple as calling forth the deer. The dances and music enter and honor the deer’s own perspective: the dancers wear antlers and imitate the movements of deer, while the lyrics are often cast in the deer’s voice. “With a cluster of flowers in my antlers, I walk.” A native Yaqui speaker and a white academic co-authored the book in 1987; they fill it with images, translations and anecdotes, like a personal tour of the Yaqui world.

The Radiant Lives of Animals by Linda Hogan

From her small house in rural Colorado, the Chickasaw poet Hogan charts a way of listening and co-habiting with wild animals that is often revelatory in its simple lack of dominance. Instead of spraying wasps who nest in her bedroom, she opens the window for them every morning so they can go in and out. “Not being a person… with insect hatred,” she demonstrates that animosity and fear of the wild are choices, just as easy not to harbor. In a lilting, dreamy voice, through the Yaqui deer dances and Hogan’s ties to horses and burros, this book of mostly essays explores the enchantment that brings humans into receptivity toward many species’ intelligence—ants, elk, wolves—“all citizens here.”

The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature by J. Drew Lanham

Through linked essays, Lanham becomes our guide to the landscape of his South Carolina childhood, where his forebears were farmers and pillars of Black community life. Birds and other wildlife captured Lanham’s attention early; he longed to fly, tempted vultures by playing dead, and gradually realized that his religious feelings were more centered on the outdoors than on church. As an adult, he became a birder and a professor of wildlife ecology—a rarity in both largely white realms. He expands our notion of who belongs in the outdoors and who loves wild places: “I also think about how other Black and Brown folks think about land,” he writes. He’s at his most convincing when he describes becoming a deer hunter, fully and consciously involved in the life and death dance of the land he loves.

The Covenant of the Wild: Why Animals Chose Domestication by Stephen Budiansky

Budiansky, a science writer and former Nature editor, makes a case here that domestication of animal species is not a process of enslavement but simply part of evolution. Both parties benefitted, he argues, when humans began to offer food, shelter and protection for species that in turn provided meat, milk, hides and labor. He traces the long, gradual process by which “loose associations” become codified, often hinging on the trait called neoteny — a tendency to retain some juvenile characteristics even in adulthood. Both domesticated animals and humans display neoteny, and collectively it has served our numbers very well: the total biomass of land species on Earth is becoming more and more weighted toward people and the animals we control. “Wild,” then, is a contested and precarious category.

Woman the Hunter by Mary Zeiss Stange

An academic and hunter, Stange investigates a string of questions animated by the presence of the female hunter—who, she points out, is not only a modern phenomenon: in hunter-gatherer societies, women have routinely killed small animals as part of what gets labeled “gathering.” Why does anyone hunt in the modern world? What can hunting tell us about the human presence on earth, and whether “wildness,” as we’ve imagined it, really exists? When the hunter is a woman, Stange argues, she awakens fertile contradictions lying deep beneath our culture: Artemis, for example, is both a death-dealer and a protector, a patron of animals who also embodies the fact that, in Stange’s words, “life feeds on life.”

Read the original article here