Three weeks after my third book came out, I experienced the first unmasked autistic shutdown of my life. What happened was this: driven into the ground by overwhelm—over-stimulated from doing larger events than I was accustomed to doing and feeling visible to readers in ways I’d never been before—I found myself unable to speak for much of the next twenty-four hours. True to the many descriptions from students and friends and personal essays and forum postings I’d consumed over the years, the external world became all the more external to me: unpleasantly busy and chaotic and loud, a violent sensorium that appeared calibrated to uniquely antagonize my cotton candy-wadded mind. To boot: I had the hellacious task of navigating O’Hare International Airport in this state. The day after my shutdown saw me hobbling hollow-eyed in a massive pair of sound-canceling headphones through the hostile fluorescence of O’Hare’s Terminal 1, wondering why everything seemed to hurt so goddamn much.

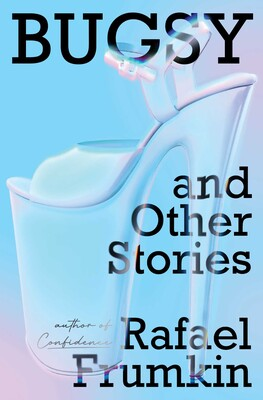

An uncharitable read of this situation—the kind toward which, regrettably, most online discourse is often inclined—is that it’s pretty darn convenient that Rafael Frumkin had his first classic nonverbal shutdown just in time for the publication of a story collection featuring a nonverbal ASD narrator. A story over which I had spent a good deal of time agonizing, had strategized about with both my agent and editor, had even crafted a short author’s note for (which, while certainly well-intended, ultimately did more to equivocate than explicate). At the forefront of my mind at all times: How will I pre-empt cancellation? How will I make a case for myself as a politically acceptable author of this piece, thereby legitimizing it artistically? How can I answer every single question about this piece before it’s asked?

All of that hand-wringing and all those emotional tithes paid to a literary discourse that frequently demands proof of an author’s claim to “authority” on a certain marginalized experience. Preparing for the backlash (some of which had already started to come), rehearsing my answers to potential reader questions, rehearsing my response to a Q&A gone suddenly south. All that, and there I was, totally nonverbal in O’Hare, experiencing with a bracing immediacy many of the feelings described by my story’s oft-overwhelmed nonverbal protagonist.

Autism began as a psychiatric designation intended more to strip people of their subjecthood than to better understand them. As a diagnosis, autism didn’t appear until fin de siècle European doctors like Eugen Bleuler identified it as either a facet of, or coextensive with, schizophrenia, labeling autistic children “childhood schizophrenics.” Much of the clinical literature about these children concerns their unintelligibility—unlike neurotypicals, they constitute a rather unpredictable series of outputs to any given input. To be an autistic-schizophrenic was to be unreadable and therefore a cognitive null set: We can’t imagine what someone who’d behave this way may be thinking, so they must be thinking nothing at all.

It’s telling that included among Autism Spectrum Disorder’s “experts” throughout history, you’ll find physicians attracted to eugenics, either coded or overt. One egregious example: Hans Asperger, for whom Asperger’s Syndrome is named, was a Nazi sympathizer highly compelled by the concept of “racial hygiene.” Rather than explore the supposedly unknowable interiority of the autistic, there has been (and remains) a medical/psychiatric campaign to banish it altogether. A diagnosis of autism is frequently seen as an automatic tragedy, a thing to be remedied with drugs and behavioral therapy and sometimes even chelation or shock therapy (as if such a thing could ever be reasonably described as “therapeutic”). Just as it was over a century ago, treatment for autism is less about the alleviation of autistic distress and more about the ruthless disciplining of the autistic mind and body.

Luckily, discourse around autistic subjectivity has spiked, with whole slews of people sharing their personal experiences online. There are autistic advocates, autistic influencers, studies and first-person accounts about potential linkages between the autistic neurotype and transness, the under-diagnosis of autism in women and communities of color, and so on. The animus for the “autism moms” behind disempowering organizations like Autism Speaks is marked, and everything from TV shows to YA novels to video games that explore the complexities of autistic subjecthood are now in wide circulation in our culture. Much of this is good news: finally, the reader/viewer is privy to a story about autism other than the one told by the doctor about the autistic patient. We are granted the interiority we’ve all been hungering for, and felt so alone without.

But lately there’s been a steady seepage of discourse into the realm of the first-person account. The digital critic has moved away from battles against autism moms and ABA therapy and has started to set their sights on other autistics: Are we to accept self-diagnosis as valid? What about a formal diagnosis, but from a doctor who doesn’t use the same set of DSM criteria as the one who diagnosed me? Does the portrayal of autism in this piece of media strike me as realistic, or dangerously problematic? Is this person even qualified to be telling a story from an autistic point of view? And the answers to these questions, time and time and time again, can typically be boiled down to four words: You’re doing it wrong.

My experience in this world is one of being simultaneously visible and marked: being openly trans (and limp-wristed and high-voiced), wearing a lot of color and gauzy “feminine” fabrics, having a commonly misunderstood neurotype that has landed me in some rocky situations. For someone like me, the very fact of my existence as an author and professor with some modicum of visibility in the world is itself a subversion: What faulty wire has been tripped that I’ve been given any kind of a platform?

I am instantly flattened and reduced. What it means to be autistic is instantly flattened and reduced.

There’s an inconsistency in readers’ minds when they read my short story and then form a quick set of assumptions about me based off my book’s dust jacket. There I am, smiling into the camera, and my bio says I’ve been a part of these historically gatekept academic and publishing circles, so why should any reader assume I’m anything other than a well-regulated, “high functioning” person? Because I write books and talk about them in front of people, I must be someone who could not possibly be experiencing the world in a way at all similar to how a nonverbal autistic person experiences it.

I am instantly flattened and reduced. What it means to be autistic is instantly flattened and reduced. The categories of “autistic” and “author” are forcibly decoupled. The result? A disgruntled online reviewer (or two or three) complains that “autistic people do not need Rafael Frumkin to speak for them.” My knowledge of my character’s subjecthood is challenged, as well as my own. Proof that I occupy the correct subjectivity to author such a story is demanded. If I cannot provide that proof, I am canceled.

With the increased visibility of autistic subjecthood has come an increased demand for “authenticity” far in excess of the desire to read someone being themself and exploring ideas on the page. There’s an implicit insistence that autistic writers do one of two impossible things: 1) exactly recreate the reader’s own, hyper-individual autistic experience; or 2) write autofiction so laden with their own pain and misery that the reader must drop their criticism and concede to the writer the title of Perfect Sufferer.

It’s easy enough to understand where this demand for an impossible kind of verisimilitude originated—from Pablo Neruda speculating idly about the interiority of the Sri Lankan hotel maid he raped (a “statue,” according to him) to Alexander Maksik deciding what it must be like to be the European high school student he assaulted and impregnated in You Deserve Nothing, there are plenty of instances in which there’s an obvious need for course correction that accounts for who should tell what story and how. But even this sort of discourse has its limits: constant, turbo-charged conversations about the right to authorship have turned writing fiction into less of a pleasurable and challenging activity of self- and world-discovery and more a high-stakes identity game played with an entire readership that one can win by a strange kind of fiat. And while we may not be directly intervening on autistic bodies and minds by playing this game, we are certainly foreclosing on the possibility of a flourishing, variegated autistic literary aesthetic.

While there are many advocating for an overall increase in nuance, empathy, and understanding in American letters (as R.F. Kuang does in her superb and savvy Yellowface), the far louder conversation is about who has materially benefited from the appropriation of a point of view, and how that crooked beneficiary can be most justly punished. Take Goodreads, which has become a hotbed of polemic so intense it’s causing books to be canceled before they even hit the press. In one incredible case, Elizabeth Gilbert actually halted the release of her third book because readers were upset about its Russian setting without having read it. And while there are certainly times when the concerns about a book are justified, the intense pillorying of the individual is never going to be the way to move the collective conversation forward. The result is less a movement towards artistic equity and more an aesthetic witch hunt, an attempt to get the writer to write the words – and indeed, live the life – in exactly the way everyone else would like her to.

The intense pillorying of the individual is never going to be the way to move the collective conversation forward.

The solution: instead of being dead, the author must be undead. An alive-and-kicking author may kick a bit too hard and stir the beehive of public opinion, which might affect sales, which would certainly affect the value of the author’s next advance, and so on. The author needs to be alive enough to show up somewhere in the world, visibly tick a certain number of diversity boxes, and then hustle off to the next event, but certainly not so alive that their complex humanity is seen as anything more than a cancelable commodity. Like any zombie, their inner life is either nonexistent or beside the point. (Let’s not even get started on the various sticky aspects of that inner life, the particular opinions, ideas, and – shudder – objections buzzing around in their undead head.) More important is their capacity to serve as a kind of emotional proxy for a readership hungry for confirmation that to be different is to suffer, and that there is nothing more noble than having suffered a lot. This is the case for everyone, though it applies to marginalized writers especially. I’ve heard from many writers of color, queer and trans writers, women writers, and disabled writers the following exasperated refrain: It feels as if my misery is worth more to readers than my joy.

Art-making is a complex, by turns-gratifying-and-frustrating process whereby you alchemize your own subjectivity with that of others’ to tell a story that you hope resonates and helps at least a few people feel less alone in the world. And once you’ve completed this process—which runs most of us quite ragged—there is no guarantee that the art you’ve made will make you rich or famous, nor that it will even get published at all. But we’ve allowed ourselves to be hoodwinked into believing that stories are as tradable as commodities on the New York Stock Exchange, and it’s caused us to enter a strange netherworld of art-under-capitalism in which the reader has become a kind of scarcity-minded watchdog. There’s a sense that the writer isn’t exploring an identity expansive enough to include many individuals, but rather staking a claim to a very narrow subjecthood—and if the writer is going to be so bold as to stake that claim, they better get it right while decidedly not enjoying themselves. Both the writer and the reader seem to be under the influence of a heavily gatekept industry: getting paid for your art (never mind paid a living wage) remains an opportunity so difficult to access that there has arisen widespread suspicion and even resentment toward those who have done so. In many cases, access has come with class privilege: the writer is seen less as a voice of the people than falsely anointed by a silver spoon and built-in industry contacts. And while writers are far from being a monolith—we come from a wide variety of social and economic backgrounds, and very few of us are actually getting rich off our writing—the damage has been done: many readers and viewers now anticipate their subjecthood being misunderstood and misrepresented by the “out-of-touch” people who write books and make films, often before said books or films are even released.

Which is how we arrive at our current situation: since my autism is not visible enough, and since I have not been “held back” materially because of it, it’s believed that I’ve taken something that doesn’t belong to me and now I am rich with money or clout that is not my own. The reader in a white lab coat, checking their charts and screwing up their face, determines that I do not meet the proper set of diagnostic criteria, and that my aesthetic prognosis is poor.

An autistic shutdown can be triggered by a variety of things, but the key culprit is always some sort of overwhelm: whether your senses are suffused with too much noise and light or you have been assigned the task of navigating a high-stakes social situation with an arcane script known only to a select few, you have quite simply had enough, and the “social functionality” program that’s always running quietly in the background of the central processing unit of your mind—permitting you to nod and joke and smile and make the kind of conversation that puts yourself and everyone else in the room at ease—encounters an error message, which means your entire system needs a reboot.

What had me needing a reboot was the simple fact of being seen. I was doing events for my book that were better-attended than any events I had ever done in the past, an experience both thrilling and, as I was quick to discover, immensely draining. With more eyes on me and my work came more instances of both praise and scrutiny, and I was finding myself quite overwhelmed by both. A friend described the experience of giving a reading to an adoring packed house and feeling extremely buoyed by the event until the final person in the signing line looked him dead in the eye, smirked, and said: “Now that your book is so successful, are you going to turn into a complete asshole?” And though I have yet to experience commercial success on the scale of my friend’s, I still found his story highly relatable. The amount of conversations I was having in which I was seen as less a person than an irksome concept was beginning to wear me quite thin. Time after time, people wanted to talk about how I had suffered as a neurodivergent queer and trans person, and how commonplace it is for people in my subject position to suffer. And if the conversation wasn’t about suffering directly, it was about the slight uptick in my commercial success as a writer, and how that could possibly be used to raise awareness of widespread suffering.

Since my autism is not visible enough, it’s believed that I’ve taken something that doesn’t belong to me

While the thematization of marginalized suffering was groundbreaking at the point in time when hearing from marginalized voices was vanishingly rare, it is no longer a needle-moving aesthetic strategy. There’s nothing subversive about the undead author staggering from bookstore to bookstore to confirm to rapt audiences that, yes, to be alive and marginalized is to be in constant, howling psychic pain. And it’s not that I don’t want to talk about the hard stuff, either—it’s just that there’s also so much that’s not hard. There’s such great joy to be had in experiencing the world with the technicolor hyper-empathy my neurotype affords me, or in contributing to the destabilization of the cisheteropatriarchy simply in the ways I speak, act, and dress. It makes one wonder about the political potency of joy, of what sort of narrative better stands to undercut the necropolitics of the Powers That Be: one in which people like me are constantly being killed, committing suicide, being policed, and policing each other? Or one in which people like me are alive, happy, and loved?

Here is how I think we need to approach subjectivity in fiction: not as a highly circumscribed reflection of an agreed-upon set of traumas, nor as penance for the privilege of getting to write and publish the fiction in the first place, but as an opportunity for subversion. An opportunity to reclaim the narrative. It might be liberatory for both writer and reader if the reader could treat books as singular reports on singular experiences, could actually adopt a sense of curiosity about how a narrative diverges from a certain subjecthood’s commonly held criteria instead of demanding an impossible “authenticity” that may not exist in the first place. Wouldn’t it be a relief if we could all take off our lab coats and read stories without worrying whether the author meets a specific set of diagnostic criteria? Epistemically speaking, who should the neurodivergent reader trust more: the actual flesh-and-blood weirdo writing the story, or the diagnostic manual that more or less identified autistic children as cognitive null sets for decades?

Time after time, people wanted to talk about how I had suffered as a neurodivergent queer and trans person.

There is a vanguard of joy-on-the-margins fiction: I am a part of it because I am also living it. And yes, I realize that doing so is not without risk, that there is immense cultural inertia when it comes to acknowledging that I—or a Black trans woman, or a Native nonbinary kid, or a disabled queer agender person—could actually be happy. But if there’s one thing you learn from a lifetime of being different, it’s that you can’t rely on a broad public consensus to tell you anything true about yourself.

While there’s nothing stopping our literary culture from continuing to demand my pain, there’s also nothing saying I have to give it away. We’ll have to save the story in which I am gaslit, suicidal, and chemically altered for a more fitting cultural moment. Instead, I’d like to tell you the story in which I am barefoot in a beard and gauzy floral skirt, laughing and running across a field of grass towards my beloved chosen family, the lot of us about to build our own little faerie kingdom in the woods. And I want you to believe me when I tell this story, to trust me without needing endless elaboration and justification. Because it’s far truer than you’d think, this story, and it has a moral: us cheerful weirdos are not an exclusive lot. In fact, the only requirement to join is that you recognize the potential of your happiness to move mountains.

Read the original article here