Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

During the current coronavirus pandemic, as every country tries to balance significant job losses in most sectors with insufficient numbers of essential workers, our work is more personal and more political than ever. The boundary between the home and the workplace has all but disappeared. The web of interactions between workers, bosses, customers, and suppliers has become more critical, complicated, and challenging.

Dhumketu, my mother’s favorite storyteller and a short story pioneer in the Gujarati language, often wrote: “Society is shaped by individuals. But an individual is shaped by work.” I am the sum total of the 20-some varied jobs I’ve had since my late teens. So most of my fiction and nonfiction also centers the working life. My story collection, Each of Us Killers, was written during the 2014-2018 period, when I’d moved back to India for a few years, and focuses on how socio-cultural divides like class, caste, gender, race, nationality, and more drive our aspirations and struggles at our workplaces.

That said, William Faulkner’s observation is also spot-on:

“. . . the only thing that a man can do for eight hours a day, day after day, is work. You can’t eat eight hours a day, nor drink for eight hours a day, nor make love for eight hours — all you can do for eight hours is work. Which is the reason why man makes himself and everybody else so miserable and unhappy.”

The Paris Review, The Art of Fiction No. 12.

No surprise then that many fiction writers have found, in that particular misery and unhappiness, plenty of grist for the writerly mill.

Yet, it’s only been in recent times that the mainstream publishing ecosystem has been spotlighting work-centered fiction. And, with fiction from or about India, there continues to be a strong Western preference for certain timeworn tropes: the family or lovers torn apart by the Partition, the aspiring slum-dweller, the miserable wife of an arranged marriage, the fervent fundamentalist, the crooked politician, the nagging mother-in-law, the homesick immigrant, etc. with characters’ professions and occupations often remaining under-explored, peripheral details. So here are some novels from India that eschew those tropes and center working lives. Each has been, in some way or other, part of the DNA of my own stories.

The Guide by R. K. Narayan

I came to this 1958 novel after watching the classic movie version. Raju, the protagonist, starts off as an opportunistic local tour guide, becomes the smooth-talking talent manager of his married-but-estranged lover, and finally gets mistaken for a great holy man. We see both Raju’s evolution and devolution as he journeys through these three occupations. Set in Narayan’s famous, fictional town, Malgudi, the novel’s prose moves from gentle humor to somber philosophy as it explores many sociocultural nuances and biases, which exist even today.

Chowringhee by Sankar, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha

Set in the cosmopolitan Chowringhee neighborhood of 1950s Calcutta, this novel is about the loves and lives of people who work at or frequent The Shahjahan, the oldest and largest hotel. The protagonist and narrator, Shankar, works there and acts as both an observer and a participant as he navigates rapidly-evolving values in a post-Independence world. The city and the hotel are very much also multi-faceted characters in the story. It’s important to point out that the novel predates Arthur Hailey’s The Hotel and enjoys cult status via plays, movies, and TV adaptations in India even today.

The Legends of Khasak by O. V. Vijayan, translated from Malayalam by the author

Like R. K. Narayan’s book above, this novel is also set in a fictional place. Khasak is a remote village in the Kerala countryside. Ravi arrives to take charge as the only teacher at a makeshift school. As he deals with all the villagers and children, incidents merge into a surreal narrative with myths, legends, fables, stories within stories, historical encounters across time and space, and more. The author’s own English translation stands apart from his original text but it is just as richly textured. And, like the previous two novels, this one enjoys cult status across several forms of media in India and has been translated into several Western languages too.

English, August by Upamanyu Chatterjee

In the 1980s, the divides between urban and rural India were more pronounced than ever before. Chatterjee, a civil servant, writes about a young, urban IAS officer, Agastya. Stationed in a rural village and unable to sustain any interest in his government and administration work, Agastya is endlessly bored. His mind snags frequently on marijuana, masturbation, and English literature. His wry observations about everything happening (or not, as is often the case) in his life range from bitingly funny to absurdly tragic. Though certain aspects of the storytelling haven’t dated well, the novel remains an authentic portrait of the educated Indian youth trying to figure out their place in 1980s India.

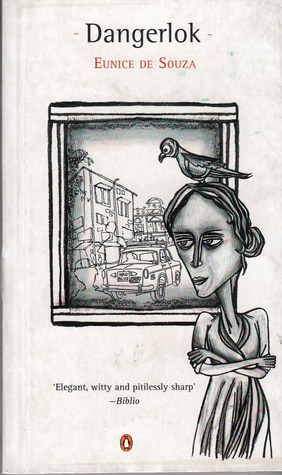

Dangerlok by Eunice de Souza

Eunice de Souza was a tour de force in the Indian literary world as a professor, critic, poet, writer, editor, stage actor, and director. She only wrote two novels, though, and this one has a protagonist modeled after herself. Rina Ferreira teaches English Literature, lives alone with two parrots and a huge personal library, and writes letters to David, a man she probably still loves. Dangerlok, or dangerous people, are all around her daily and become the subjects of her vivid letters. The writer gives her protagonist lots of room to play and creates such a varied, wonderful world for her to inhabit that, as readers, we never want to leave it.

Hangwoman by K. R. Meera, translated from Malayalam by J. Devaki

Meera’s works have always addressed issues like patriarchal discrimination, power dynamics, and women’s independence. The protagonist here, Chetna, comes from a long line of executioners and is appointed the first woman executioner of India. This makes her an overnight celebrity but the noose is now a metaphorical thing around her own neck that she must wrestle with. Meera’s attentiveness to every small detail complements her dark humor and the plot’s twists and turns. Heritage, history, crime, mystery, justice, life, death, love, tenacity, endurance—this novel has it all. The English translation does have a few road bumps, however.

Fence by Ila Arab Mehta, translated from Gujarati by Rita Kothari)

A young woman, Fateema, dreams of a stable job, economic independence, and a home of her own. But she’s Muslim in the Hindu-dominated state of Gujarat and from the lower strata of society. So these are not simple or basic aspirations for her. She’s expected to resign herself to living in the Muslim ghetto neighborhoods of her city. She’s also ridiculed and ostracized by her own minority community for wanting so much. Mehta writes about a highly-charged, complex topic in Gujarat even today: the Hindu-Muslim divide. And Kothari’s translation of the original text with its several different Gujarati dialects is a multilingualism masterclass.

Temporary People by Deepak Unnikrishnan

This book is the only one on this list not set in India. But Unnikrishnan’s award-winning linked story collection about Indian (mostly) guest workers in the United Arab Emirates was rightly hailed as a new kind of immigrant narrative when it came out. Using hybrid narrative forms, surreal symbolism, mythology, and dark satire, these accounts highlight how economic, professional, and social progress can often lead to dehumanization. Linguistically, Unnikrishnan blends English, Malayalam, and Arabic to create a unique polyphony of voices that stay with us long after reading.

A Meeting on the Andheri Overbridge: Sudha Gupta Investigates by Ambai, translated from Tamil by Gita Subramaniam

Ambai is a Tamil writer well-known for her feminist literary works. At the age of 72, she departed from her usual oeuvre to write detective fiction with a middle-aged woman protagonist. In true Ambai style, she eschews the traditional whodunit for a deeper exploration of human vulnerabilities, social hierarchies, and sociocultural power dynamics. Set in Mumbai, this is a collection of three novellas depicting an everywoman who works as a private detective and takes care of her family—balancing both with a well-cultivated support network. She’s strong-willed but tender, pragmatic but takes no prisoners, efficient but always accessible.

Requiem in Raga Janki by Neelum Saran Gour

Gour’s writing has mostly focused on small North Indian towns and their rich histories. This novel is based on the true life of an early 20th-century royal courtesan-singer, Janki Bai. Among many well-known legends about her, there’s an incident where she survived a heinous stabbing due to her work, winning her the nickname of “Chappan Churi” meaning 56 knives. As we journey with Janki Bai from girlhood to matronhood, we see how her musical vocation shapes, torments, and restores her. Beyond Gour’s thorough research into the socio-political history and music of the time, the musicality and element of play to her narrative renders the life of this amazing artist with multiple resonances of meaning and texture.