If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

While the idea of Blackness is very much associated with the United States of America, the first Africans in the historical record to enter the Americas were, in fact, Afro-Latinxs. African-descended populations peopled Central and South America in large numbers long before they were deposited by slavers in places like Jamestown, Virginia and Plymouth, Massachusetts. This fact matters because it suggests how America-centric our understanding of transatlantic slavery and the history of the Americas is.

Whether writing about the past, the present or the future, Afro-Latinx writers grapple with issues of identity and hybridity, immigration, isolation and assimilation, and what it means to occupy the nexus point between Blackness and Latin Americanness, two identities that within the United States context are still deeply marginalized.

As a writer myself, I am interested not just in the stories that are marketed in the mainstream, but those stories that happen on the margins. My novel The Confession of Copeland Cane is a story that is on its face about police violently vamping down on Black boys and men, but in its totality speaks to not just that reality, but also environmental injustice, over-medication, over-sentencing, and, finally, the possibility of escape from an increasingly unfree American future. Like Copeland’s cordoned world, the Black diaspora is sectioned off by national borders and language barriers, but literature, whether of the future or the past, has the ability to reach across these lines.

Here’s a brief list of Afro-Latinx fiction writers current and past whose work traverses the Americas.

Naima Coster

Dominican American writer Naima Coster’s novels Halsey Street and What’s Mine and Yours showcased her brilliance as a major literary talent. Coster’s work explores an array of headline issues through the intimate prism of American families in all their love, diversity, dysfunction, and denial.

Halsey Street, which was a finalist for the Kirkus Prize, chronicles a set of circumstances that too many Black Americans know too well: The burdens borne by a family as they deal with the spidering impact of gentrification upon their Bed-Stuy, Brooklyn community.

The just-published What’s Mine and Yours was inspired by the 1619 Project reportage of Nikole Hannah-Jones on the integration of a Missouri school district. Coster sets her novel in a North Carolina town instead, but at the heart of the book is more than a clash of racial prerogatives, but rather an intimate multi-family saga of two mothers—one Black, one white—and their children, the objects of the integration debate.

Aya de Leon

Aya de Leon is a heist fiction novelist, an emcee, a scholar of crime fiction in film and books. As a novelist, de Leon came to national prominence with her widely acclaimed novel Uptown Thief. The heist narrative set in Spanish Harlem features a former sex worker turned Afro-Latina Robin Hood, Marisol Rivera, and the battered women, most of them sex workers, whom she shelters. But de Leon was already well-known in Bay Area spoken word poetry circles as the creator of the one-women hip-hop theatrical Thieves in the Temple: The Reclaiming of Hip-Hop, a production which anticipated Lin Manuel Miranda’s more famous hip-hop theatrical (perhaps you’ve heard of it) by almost ten years.

Though the Bay Area is de Leon’s adopted home, she’s a native New Yorker and her fiction is set there, as well as Puerto Rico (she is of Afro-Puerto Rican heritage) and Cuba. Since publishing Uptown Thief, de Leon has gone on to release a series of Black feminist street lit novels that turn the narrative conventions and sexual and economic politics of the genre on their head. Meanwhile, drawing on her scholarship—de Leon is a professor at the University of California—she has written incisive essays on a range of issues, from analysis of detective literature, to #metoo, to prime-time TV’s celebration of police violence.

Elizabeth Acevedo

Dominican American poet and novelist Elizabeth Acevedo is one of the great young writers in America. Acevedo’s wildly successful debut Young Adult novel The Poet X received the 2019 Walter Dean Myers Award for Outstanding Children’s Literature, the 2018 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, and was a 2018 Kirkus Prize finalist. Subsequent novels With the Fire on High and Clap When You Land have further established Acevedo as a major voice in contemporary literature. She is a CantoMundo and Cave Canem fellow, which represents her dual poetic identity within the Latinx and Black poetry communities.

Aja Monet

Cuban Jamaican, East New York-raised Aja Monet became the youngest winner of the Nuyorican Poets Café’s Grand Slam. The year was 2007. She was 19-years-old. You can read and listen (on audiobook) to Monet’s surrealist blues poetry and storytelling in her chapbook The Black Unicorn Sings and in the anthology Chorus. Her first full-fledged book of poetry, My Mother Was a Freedom Fighter, received critical acclaim, as well as a nomination for a NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work.

As an activist organizer in South Florida’s Little Haiti, Monet has co-founded a political safe-haven for artists and organizers called Smoke Signals Studio.

Jamie Figueroa

Jamie Figueroa is a Puerto Rican novelist of Afro-Taíno descent. She published her debut novel Brother, Sister, Mother, Explorer in February 2021. The novel has received praise from the New York Times, LitHub and Publisher’s Weekly. I’m looking forward to this fine novel receiving the readership that it deserves. Figueroa writes:

“One marker of the ongoing colonial project is the refusal to acknowledge the complexity of identity and the polyphony of perspectives within the construction of a single category of race and ethnicity…

Blending the boundaries of poetry and prose, revealing true names and renaming as a way to expose additional truths, as well as questioning ‘reality,’ are some of the ways I actively engage in decolonizing my imagination.”

Sofia Quintero a.k.a. Black Artemis

Puerto Rican Dominican writer Sofia Quintero—who publishes both under her government name and also as Black Artemis—is the author of Explicit Content, Picture Me Rollin’, Divas Don’t Yield, Names I Call My Sister, Efrain’s Secret, and Show and Prove. A master of hip-hop fiction, also commonly called street lit, Quintero in her Black Artemis alter ego is often grouped with African American writers of the hood like Vickie Stringer, Sister Souljah and Terri Woods. But, like so many writers of color, Quintero’s work is too easily type-cast.

In fact, in Quintero’s debut as a Young Adult novelist, Efrain’s Secret, the author explores the harrowing risks that Efrain Rodriguez, a South Bronx teen, must take just to be accepted to an Ivy League college. In her follow-up, Show and Prove, Quintero chronicles the lives of two South Bronx teens in 1983, as hip-hop suffuses the streets of New York City.

Paulo Lins

The Afro-Brazilian novelist Paulo Lins got his start in the streets by writing songs about his favela’s many gangsters for the local samba singers to sing. The mayhem that those gangsters and the cops who battled them inflicted upon the Cidade de Deus favela became Lins’s subject.

By far Lins’s most well-known work is Cidade de Deus (City of God), an all-out, maximalist narrative of the chaos, violence, and community of one of Rio de Janeiro’s most infamous favelas. Immortalized for mainstream eyes by the film City of God, Lins’s wild vision of Brazilian city squalor has had as powerful of an impact on global understanding of urban hardship as Richard Wright’s Native Son, Sister Souljah’s The Coldest Winter Ever, and Boyz n the Hood.

Nicolas Guillen

Nicolas Guillen was an Afro-Cuban poet who played a prominent role in the Harlem Renaissance. Guillen’s father introduced him to son music, an underground West African musical form that was heavily persecuted by Cuban authorities in the early 20th-century as part of a larger campaign of anti-Blackness. Guillen, like all Black Cubans, experienced systematic anti-Black racism little different from what Black people across Latin America and the United States experienced during the first half of the 20th-century.

Like son music itself, Guillen’s poetry synthesizes Cuba’s mixed African and European culture. In 1930, Guillen met Langston Hughes, the most famed poet of the Harlem Renaissance. Guillen and Hughes hung out together in Havana and Hughes inspired Guillen to publish Motivos de son, a book of eight poems about Afro-Cuban music and life that made Guillen’s international reputation, elevating the status of Black Cubans.

With subsequent books, including West Indies Ltd., Guillen’s poetry became increasingly political, advancing the Negritude movement and political Marxism. Along with Hughes and Hemingway, he traveled to Spain during the Spanish Civil War. With the tumultuous cold war intrigues of the 1950s, Guillen was exalted by the USSR, exiled from Cuba by the Batista dictatorship, then brought home with Fidel Castro’s revolution, and finally installed by the communist dictatorship as the head of the nation’s writers’ union. Guillen upheld the ideals of the revolution until his death.

Piri Thomas

“I am ‘My Majesty Piri Thomas,’ with a high on anything, and like a stoned king I gotta survey my kingdom. I’m a skinny, dark-face, curly-haired, intense Porty-Ree-can—

Unsatisfied, hoping, and always reaching.”

So begins Down These Mean Streets, Piri Thomas’s powerful autobiographical debut novel. But before he was a writer, Piri Thomas was a career criminal, a heroin addict, a burglar, a felon who shot a cop. He ended up in prison and would have to carry his rap sheet to the grave. Then, at 39 years of age in 1967, Thomas turned his life around and became a writer, a writer of exceptional accomplishment.

Named after a poetic flourish in Raymond Chandler’s “Simple Art of Murder” essay, Thomas’s novel takes readers down the mean, gang and drug-ridden streets of Spanish Harlem, down into the Jim Crow South, where young Piri attempts to connect with his Black heritage, and back to Harlem, where his Eurocentric family and inner-city demons reside.

An Afro-Puerto Rican novelist, Thomas was immediately taken up as part of the Black Arts Movement of the late 1960s upon the publication of his seminal novel. As such, Thomas is the main forerunner of the Nuyorican poetry movement and Afro-Latin literature in America in general. His work is also regarded in the vein of the street-hardened 1960s narratives penned by Iceberg Slim (Pimp) and Claude Brown (Manchild in the Promised Land) as an example of early street lit, forerunner to the works of current-day street scribes K’wan Foye, Black Artemis, Aya de Leon, and many others.

Manuel Zapata Olivella

Along with the Afro-Colombian poet Calendario Obeso, Zapata Olivella is the premier figure in Afro-Colombian literature. His masterpiece is his 1983 novel Chango, el gran putas (Shango, the Biggest Badass). If the title alone doesn’t do it for you—though I’m guessing it does—the book’s epic, tragic, heroic scope will. Unfortunately, few readers in the English-speaking world have even heard of Zapata Olivella, let alone read his work.

The basics of publication and reader access are still an issue for many a great book written by Black writers across our diaspora. Despite being every bit as ambitious and as innovative with its use of myth and time as the famed magical realist text One Hundred Years of Solitude, Chango, el gran putas is very difficult to procure as an English-language text. It’s a shame because the book brings under its veil Afro-Latin, Afro-Caribbean, African-American and mother continent folklore, gods, heroes, and history. Truly one of the most ambitious books published about the African diaspora, Chango tells the entire sweep of the post-Columbian Black world, from orichas, to slave rebellions on the islands and in Brazil, to the civil rights struggles in America in the 1960s.

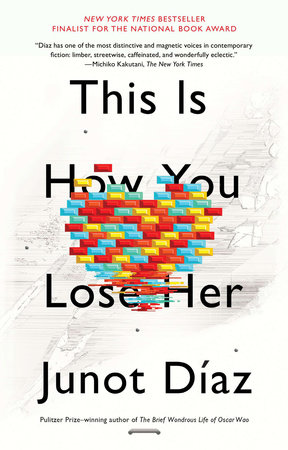

Junot Diaz

Junot Diaz’s short story collection Drown is both a portrait of life at the impoverished edges of the Dominican Republic and a rugged bildungsroman that, in the main, follows Yunior, a child whose family escapes the political violence and poverty of the D.R. only to find themselves in the urban squalor of ’80s era New Jersey. The book’s finale, the story “Negocios”, is an archetypal American immigration narrative that Diaz delivers in painstaking detail.

Diaz returns to Yunior as a far less sympathetic adult in the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. A more ambitious book than its predecessor, Oscar Wao encompasses much of mid and late 20th-century D.R. history, as well as a complicated, hyphenated, semi-absurd American present. The book’s emotional heart is not Yunior, but his attitudinal antithesis, the nerdy and star-crossed Oscar Wao.

This is How You Lose Her, Diaz’s third book and second collection, brings together many of Diaz’s best short stories. “Otravida, Otravez” is told from the perspective of Nilda, a major character in “Negocios,” thus presenting an alternative to Diaz’s male-dominated immigration narratives. The collection also returns to Rafa, Yunior’s street-hardened brother, tracing his romantic life and hustles. Diaz is also an essayist of some note: His “MFA vs. POC” essay, in particular, has had an influence on the structuring of MFA creative writing programs.