Electric Literature Urgently Needs Your Help

For the 15,000 people who visit our site every day, reading Electric Literature costs nothing. And yet Electric Lit is not free. We need to raise $25,000 by December 31, 2024 to keep Electric Literature going into next year. If the continued existence of Electric Literature means something to you, please make a contribution today.

I yearn for a literary world where, as readers, we’re familiar with a wider spectrum of narrative traditions and approaches than what we now think of as the canon. We Bengalis love so much to talk, to weave tales, to let our anecdotes tangle with each other’s into a larger collective imagination. We love our adda—those hours of conversation over cups of cha, over plates of bhaat, daal and bhorta, at the doorstep where we continue to linger before leaving the party. True to Bengali hospitality, I want readers around the world to share in this love of spinning stories, and using language for social change.

South Asian literature is still starting to make space for itself in western publishing. Within that niche scene, Bangladeshi narratives are often mixed up with, left in the shadow of, or perceived through the prism of literature from India or Pakistan. The reality is that very few western readers are familiar with the vast ocean that is Bangladeshi literature, which contains within it stories of Bangladesh’s ethnic diversity, as well as the world of Bengali literature, i.e. literature penned in the Banga language or written by Bengalis from Bangladesh (as opposed to Bengali authors from India’s West Bengal). In politics, these categories divide. In art, we remember that we all share a common heritage, whose experiments in history, romance, politics, satire, folk tales, magic realism, science fiction, and thriller all coalesce into a rich tapestry of imagination and testimony. When readers aren’t interested in an art form, publishers struggle to accommodate it. When publishers don’t make space for an art form, readers remain deprived. In the absence of familiarity, we overlook, misunderstand, stereotype. What’s beautiful about literature is that it takes one real moment of contact between a reader and a text to bridge these gaps, and what follows is a truly unique relationship that transcends obstacles of commerce and space and time.

The authors in this list, which is by no means exhaustive, write from Canada, the United Kingdom, India, and parts of the United States. Through their stories, they help bring Bangladesh—its space, its words, its people, its pains and moments of miracle—closer to a readership that is still beginning to understand it.

Bengal Hound by Rahad Abir

While many books portray Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971, Abir’s debut novel is among the few that take us back to the ‘60s, when East Pakistan was gearing up for the mass uprising of a nationalist movement. Britain’s partitioning of India and Pakistan has left the region in a storm. Families are separating from each other and from their own land under the strange order to live where their religion, and not their home, resides. Hindu minorities are the prime targets of attack in Pakistan.

Shelley is one such Hindu man in East Pakistan (what is now Bangladesh), a student of English literature bearing the name of the British poet. Roxana, a Muslim woman, his childhood love. Their relationship becomes a mirror for the religious differences tearing the region apart. Amidst this chaos of Hindu-Muslim riots and student revolutions, Bangladeshi author Rahad Abir—a PhD candidate of creative writing at the University of Georgia—brings to life the historic campus of Dhaka University, Madhur Canteen, and Fuller Road, where decades of Bangladesh’s cultural and political past have unfolded. More literally, he brings to life the statue of a beloved character whose death pierces the story early in the novel. The book becomes an exploration into the human mind—how it processes loss when love and politics become embroiled.

The Children of this Madness by Gemini Wahhaj

Gemini Wahhaj is a Bangladeshi writer based in Houston, an associate professor of English at Lone Star College. Her debut is a novel told in voices, set partially in the time of America’s invasion of Iraq and, at other times, in Bengal’s past through the Partition and later Bangladesh’s independence. Nasir Uddin is an engineering professor, a hero to his now grown and successful students. His first-person recollections take the reader through his own impoverished past set against the region’s political turmoil. Interspersed with his memories are the present life of his daughter Beena, a PhD candidate studying English literature in Texas. Beena’s allegiances to the idea of home form the emotional core of the novel, as she navigates between Bangladesh, which her parents call home, Mosul, where she spent parts of her childhood, and America, where her adult life as a scholar and a wife bristle against the US’s invasion of Iraq.

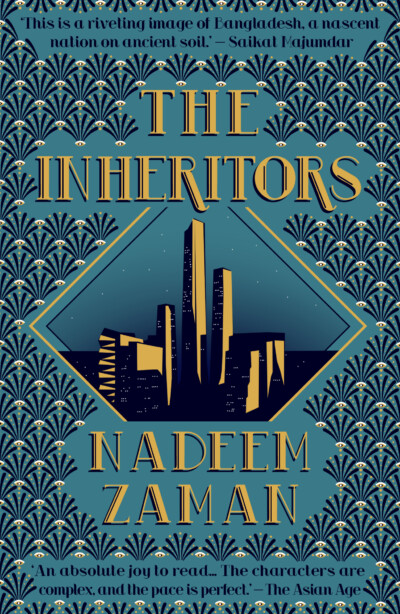

The Inheritors by Nadeem Zaman

The Great Gatsby set in Dhaka. Nisar Chowdhury, Zaman’s version of Nick Carraway, is a Bangladeshi expat based in the US, forced to revisit Dhaka to sort out his family’s real estate transactions. A rich businessman by the name of Junaid Gazi wants to buy his properties, particularly the one facing—you guessed it—the house of a woman named Disha, Nisrar’s first cousin. Like Nick, Nisrar casts a writer’s gaze on Disha and Gazi’s story; unlike Daisy and Gatsby, the Bangladeshi couple are spouses estranged by divorce. The Inheritors is the fourth book by Nadeem Zaman, who teaches in the English department at St. Mary’s College of Maryland. His adaptation of Fitzgerald’s classic takes a look at Dhaka, old and new, to critique the lives of its elite society.

Good Girls by Leesa Gazi, translated by Shabnam Nadiya

Lovely and Beauty are sisters, 40 years old on the day this novel takes place. Their mother, Farida, has never let them out of their home alone. Today, though, on her birthday, Lovely is allowed to venture into Dhaka on her own. For only a limited amount of time.

Leesa Gazi is an author and filmmaker based in London whose work with the Komola Collective promotes untold female narratives through theatre. In this translation by Shabnam Nadiya, a graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Gazi’s taut, tense prose takes us through Lovely’s first day of moving about in a city full of risks and possibilities for a young woman in touch with her desires. We travel with Lovely through Dhaka’s familiar streets, to the alleys of Gawsia Market, where women buy their clothes, and through tense rickshaw rides to the temptations of Ramna Park, where Dhaka’s lovers meet. We get a taste of what freedom feels like when it’s a rare privilege, and the sinister things that fester in its absence.

In Sensorium by Tanaïs

“We still say the Urdu word —ab-o-hawa, water and wind—for weather. We’d never deny a beautiful phrase. We say pani, as Bangladeshi Muslims, the word for water used throughout North India and Pakistan. West Bengali Indians use jol or pani, interchanging the words depending on whom they’re speaking to. Bangladeshi Hindus will say jol, distinguishing themselves from the Muslim majority. Both words can be traced back to Sanskrit, paniyam the word for drinkable; jala the word for water. Language, down to a single word or phrase, might reveal whether we were Muslim or Hindu, starting with all our separate words for water, bathing, hello, goodbye,” Tanaïs writes in their memoir.

Tanaïs is a writer and self-taught perfumer, an American Bangladeshi Muslim femme artist who grew up in the US’s South, Midwest, and New York. Through the refracted lens of these perspectives, In Sensorium crafts an olfactory memoir, braiding South Asia’s diverse pasts with Tanaïs’s journey through their cultural, spiritual, sexual and artistic identities. The book is divided, like a perfume, into Base, Heart, and Head Notes. In each of these sections, the text engages with strands of South Asian history that have been shaped by power dynamics—what the author labels as ‘patramyths’—detangling a tapestry of languages, myths, rituals and spiritual practices passed down over the decades in the region.

The Startup Wife by Tahmima Anam

Tahmima Anam’s fourth novel takes us to the fast-paced, glossy world of America’s tech startup culture. Asha Ray is born to Bangladeshi parents, grows up in Jackson Heights, and pursues a PhD to develop an algorithm that will inject robots with empathy. But the accidents of love and inspiration swiftly move her from academia to entrepreneurship in a tech incubator, where the app she and her partner develop acquires cult status. The story that follows is funny with an edge, a dissection of how the tech world engages with gender politics.

Based in London, Anam acquired critical acclaim for her Bengal trilogy, which spans across milestone moments of Bangladesh’s political past. The Startup Wife is her foray into the world of tech and writing what she called, in one of our conversations, a story of “coming-of-rage”. While its setting is far from Bangladesh, Anam shared how the novel is inspired by Sultana’s Dream, an iconic work of sci-fi about a feminist utopia written by Rokeya Sakhawat Hossain, one of the first Bengali Muslim women authors to write in English in early 20th century Bengal (and discussed by Tanya Agathocleous in EL here!).

The Storm by Arif Anwar

In Cox’s Bazaar along the Bay of Bengal, a devastating storm uproots coastal lives, estranging families. Amidst World War II, a Japanese pilot and a British doctor cross paths during their stay in Burma. After the Partition of India in 1947, a married couple is forced by circumstances to move to East Pakistan and start their life anew. At some point between these events, an illiterate young girl on a beach teaches herself to read from war pamphlets showered onto her by accident. All these lives overlapped with each other at various times, and the chain of events they set in motion will help us connect the dots in the life of Shahryar, a father and struggling immigrant scholar in the US, the protagonist of the Canada-based author, Arif Anwar’s debut novel. The book illustrates the repercussions of violence and colonial presence reverberating decades into its characters’ lives. The book also imagines the impact of the 1970 Bhola Cyclone, which destroyed half a million lives in East Pakistan and India’s West Bengal.

In the Light of What We Know by Zia Haider Rahman

Rahman’s debut novel unfolds during the Afghanistan war and the financial crisis of 2007-08, moving from Kabul to London to New York, Islamabad, Dhaka, Oxford and New Jersey.

It follows two men of mathematics, old friends separated by class and life’s circumstances, one of them an unnamed banker who serves as the book’s Sebaldian narrator, and the other, Zafar, who shows up unexpectedly at his friend’s doorstep. Their reunion transcribes a story of love, power, and the possibilities of human knowledge. The novel’s settings and central concerns draw heavily from the author’s own life—born in Sylhet, Bangladesh before his family moved to England, Rahman studied mathematics at Oxford, worked as an investment banker in New York’s Goldman Sachs, and moved onto humanitarian work alongside his career in writing and broadcasting.

Olive Witch by Abeer Hoque

Abeer Hoque’s lyrical, sparse prose recreates the spaces she has known as home: Nigeria, Bangladesh, and the United States. The more discursive chapters of this memoir are interjected by brief snapshots of poems, conversations, and passages from Hoque’s time in a psychiatric ward, where the author stayed after a suicide attempt. Through these fragmented stories, Olive Witch makes space for the intimate experiences of growing up—frictions with parents, the tug of multiple cultures on one’s identity, marks left by loves and friendships, the struggles of mental health, and the clarity made possible by a relationship with the written word.

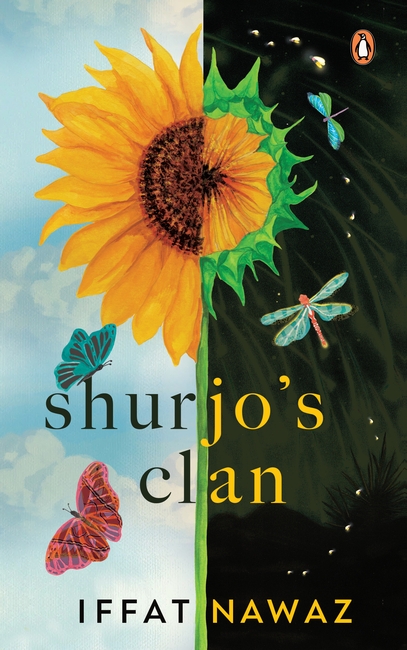

Shurjo’s Clan by Iffat Nawaz

Named after the sunflower, Shurjomukhi is born to a family that has lost two sons to war. Her father’s brothers were martyred in 1971. Her grandmother drowned years before them. But this family continues to hold each other close, living in an ‘asymmetrical’ building fashioned after the old Bengali phenomenon of the ‘der tola bari’, a one-and-a-half storey house. In this novel, the asymmetry translates into their day-to-day lives. During the day the family exists in the Known World, where regular people live and breathe. By night, the Unknown World brings back Shurjo’s uncles who have passed away—together, the family eat and chat and celebrate love as if nothing has changed.

Iffat Nawaz grew up in Bangladesh and moved to the United States after a heart attack took her father’s life on a flight. His brothers, like Shurjomukhi’s uncles, were among the first wave of freedom fighters to be martyred during the war. The impact of these absences inspired Nawaz, who writes from Kerala now. Her debut novel explores how history can affect multiple generations of a family, especially when they hesitate to talk about it.

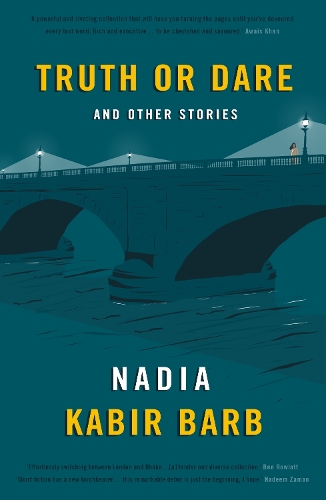

Truth or Dare by Nadia Kabir Barb

London and Dhaka emerge in bursts of hope, despair, and compassion in Nadia Kabir Barb’s short story collection. Based in England, where the author and columnist also co-runs the South Asian writers’ collective called The Whole Kahani, Barb writes about moments of truth that reveal the emotional and psychological cores of her characters. Siblings dissect the demise of their parents’ marriage in “Don’t Shoot the Messenger”. A son reckons with his late mother’s past in “Strangers in the Mirror”. A homeless man begs a promising young woman to take a second shot at life elsewhere in the collection. The stories showcase moments of intimacy in the bustle of Bangladesh and England’s urban life.

Read the original article here