Electric Lit is 12 years old! Help support the next dozen years by helping us raise $12,000 for 12 years, and get exclusive merch!

The millennial voice in fiction has been oft-discussed now for some time. Some have argued the voice is best seen in the sparse prose of Sally Rooney. Some, that it’s in the more voice-driven work of Lauren Oyler, Halle Butler, and Ottessa Moshfegh. It’s a voice that can resemble anything from a resurrected Jean Rhys, Marguerite Duras, or Kathy Acker contending with the modern world—one that reveals a person (often in the age range of “millenial”) who may be morally dubious and cerebral, tender but barbed. She talks sex candidly, and can be called selfish and unhinged. She is my favorite. She’s also almost always white.

I was in college when I first started writing fiction, and I was often told that my work had too many “different” themes going on. It’s true that my favorite books were two different sub-genres: the intergenerational, diaspora novel and the alienated, flawed, and cerebral female narrator. In the former, my cornerstones were Julie Otsuka, Sandra Cisneros, Jhumpa Lahiri, Ruth Ozeki, and Amy Tan. With voice-driven works, my shepherds were Mary Gaitskill, Aimee Bender, Amy Hempel, Sheila Heti, and Lydia Davis. I became extremely frustrated that there was no Venn diagram between these two circles, especially as my workshop classmates told me that my focus on identity and my narrator being Turkish and American “crowded” the other themes in my work, which were often these gently manic narrators contending with modern-day New York City, their families, and their sexual desire. Choose one, people would write to me. Especially if a story included a single mention of Islam.

This was between the years of 2012 and 2015. Today, I’m delighted that an intersection has begun to emerge in this venn diagram, an intersection that pushes against the idea that a “millennial” and “relatable” novel has to feature a white, strictly-American or Western European narrator.

In this stellar list, the narrators are similarly dubbed a range of darkly funny, irresponsible, or obsessively analytical. These narrators, kids of immigrants or immigrants from a young age, resist the intergenerational diaspora narrative that is often expected of them, while also reading as different from the more popular, white millennial narrator. Parents are ever-present, race is explored with a razor-sharp eye, sex and dating is really, very compromising—especially if it’s with a white American—as is any behavior that jeopardizes your chances of both assimilation and success. Identity has no easy answer and is instead an ongoing question. There is always a deeply rooted tension regarding home and belonging, and narration can easily slip into another time and across the map to the character’s respective motherland. Most notably, there’s duty and guilt: the expectation that you have to do something worthwhile with the life that your parents gave so much up for.

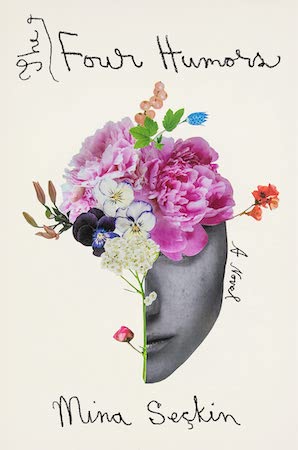

In my debut novel The Four Humors, I write towards this tension. My narrator, Sibel, is in Turkey for the summer to care for her grandmother, grieve her father’s unexpected death, and study for the MCAT. Her white American boyfriend tags along. The big problem is that Sibel has a chronic headache, and all she does is obsess over ancient medicine and watch soap operas with her grandmother. She’s an alienated, millennial narrator telling an intergenerational diaspora story—and it isn’t until she stumbles across a family secret that she’s able to shed her delusional skin. Does she find out how to live her life better? Hmm. Does anyone?

All of these narrators are asking this same question: what the hell are we supposed to be doing? Where do we belong? How, as Sheila Heti wrote, should a person be?

Severance by Ling Ma

Candace Chen is a first-generation 20-something who is still working at her office in New York City when the Shen fever-induced global apocalypse is well underway. Severance is zombie apocalypse meets dystopian pandemic meets corporate millennial horror show, told through the candid voice of Candace. Whereas most dystopian narratives serve up an run-of-the-mill, “relatable” (white) hero, Ling Ma gives us the very unique Candace, whose complicated understandings of home and belonging underpin this richly layered, prophetic novel.

Pizza Girl by Jean Kyoung Frazier

Jane is 18 and pregnant in Los Angeles when she delivers pizza to Jenny, a woman who wanted pickles as a topping, a woman with whom Jane promptly becomes obsessed. Jane’s also living with her devoted mother and smothering boyfriend, Billy, while grieving her late father’s death—and yeah, she’s drinking while pregnant.

Pizza Girl is a propulsive and sublime ode to the unexplored taboos inherent in coming-of-age, seen through its explorations of motherhood, addiction, queerness, and grief. Hope is the pulsing heart in this idiosyncratic, spectacular debut, seen most heartrendingly in Frazier’s description of the Korean phrase “han”:

“Han was a sickness of the soul, an acceptance of having a life that would be filled with sorrow and resentment and knowing that deep down, despite this acceptance, despite cold and hard facts that proved life was long and full of undeserved miseries, ‘hope’ was still a word that carried warmth and meaning.”

Call Me Zebra by Azareen Van der Vliet Oloomi

An epic and terrifically funny love letter to literature, Call Me Zebra follows self-named Zebra, an Iranian refugee and émigré, who is on a quest to write a manifesto of every book she has ever read in order to make sense of her chaotic life. Zebra, who was in-utero when her parents fled Iran, traverses from Barcelona to New York City—all while questioning exile, identity, literary theory, history, and mortality in a wonderfully-increasing histrionic and obsessive tone: “I thought to myself, I am among the loneliest of this pitiful world; all the other Hosseinies are dead.” She’s also stumped by love—especially when she meets the charming Ludo and his clique of fellow exiles. Her best friend? A “mongrel” bird she steals from a professor’s apartment.

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang

Obscene and heart-rending all in one, Sour Heart is a frank and kick-ass example of the kind of hell you can experience being a kid of immigrants. The collection of stories highlight the experience of first-generation Chinese American girls growing up in New York City in the 1990s; their dedicated parents, professionals and artists back in China, share tenement housing and one another’s dress shoes—even if four sizes too small. The devotion paid to coming of age is unparalleled—the supposedly gross, weird, and ugly, it is all turned beautiful in this collection.

Problems by Jade Sharma

Dryly funny, whip-smart, and heroine-addicted, Maya’s candor on the page about sex and addiction is groundbreaking. Just one page after Maya’s having sex (“He fucked me from behind. Felt like a baseball mitt, stretching.”), she’s describing her identity with bluntness and veiled conflictedness:

“I regularly told people my father was white. Not because of some deep-seated issue with being Indian, but because I didn’t know much about Indian culture, and I felt more American than anything else.”

What We Lose by Zinzi Clemmons

Thandi is in college when she loses her mother to cancer, inheriting an emotional and intellectual burden of how to carry on while experiencing profound loss. In powerful and lucid vignettes that incorporate visual art, photography, charts and graphs, What We Lose explores questions of grief, identity, race, and love with a poetic and analytical eye. Identity is an ongoing question in this novel, as Thandi, raised in Philadelphia to an American father and a South African mother, feels like “a strange in-betweener.”

Chemistry by Weike Wang

The unnamed narrator of Chemistry is a Chinese American graduate student studying synthetic chemistry, but her research is not going well, she doesn’t know whether to accept her boyfriend’s marriage proposal, and she is really disappointing her parents. Balancing dry wit and delectable shards of information on anything from the composition of minerals to the belief among Chinese mothers that babies pick their own traits in the womb, Weike Wang’s intimate debut is a neurologically-charged and fiercely meditative story of how an emotionally and professionally unmoored young woman navigates a world where science no longer holds the answer.

Dreaming of You by Melissa Lozada-Oliva

Raw and obsessive, Dreaming of You is a novel in verse that feels like a macabre sex education manual taught by your best friend. Melissa is a young Latinx poet who decides to bring popstar Selena Quintanilla back to life—all while experiencing panic attacks on the F train and receiving calls from her father about whether she’ll consider becoming a doctor now that NYU medical school has waived its tuition fees. This genre-defying novel is alive and spectacularly horny, with chapter titles like “I’m So Lonely I Grow A New Hymen” and “What If Selena Taught Me How to Fake Orgasms.” Family is as central to this narrative’s skeletal system as millennial angst and Internet culture: they fuse together and create a magical, death-defying body.

You Exist Too Much by Zaina Arafat

You Exist Too Much opens in Bethlehem with our unnamed narrator, 12 years-old at the time, walking by a group of men drinking tea. She’s with her mother and uncle, and she’s wearing shorts when one of the men calls out, “haram!” Haram means forbidden in Arabic, and Zaina Arafat’s debut novel deftly probes the constraints and bounds that society imposes on a queer Palestinian American woman who has always been told—even and especially by her mother—that she desires too much, and too much of the wrong thing.

Days of Distraction by Alexandra Chang

Jing Jing, a recent college graduate with an infectious and understated sense of humor, works as a technology reporter in Silicon Valley, where she’s one of the few employees of color and is trying to get a raise. When she decides to move to Ithaca with her white boyfriend for his graduate school, she begins tracing the history of racism against Asians Americans in the United States through archival research and exploring the subtleties of her own interracial relationship and complicated family story. The result is a probing and exceptionally wise story of a young woman in search of what she wants.

The Idiot by Elif Batuman

Yeah, okay! Technically Selin—The Idiot’s idiosyncratic, charming, and cerebral narrator—is not a millennial. But Batuman’s depiction of a Turkish American’s first year of college and foray into the world wide web in 1995 serves as a modern-day manual on how to navigate language—especially when you have an all-consuming crush on a senior with a girlfriend and you’re communicating via the digital landscape.

Selin’s quest is understanding language: she takes Russian, teaches ESL in Spanish, buys a new coat because it reminds her of Gogol’s, and ultimately follows her crush to Hungary for the summer. For me, Elif Batuman’s fiction was the first time I saw my own identity as a Turkish American person in literature, and The Idiot—a stupendous novel of ideas and observations that will make you laugh and nod in universal recognition—will always serve as my foundational text.