For now, at least, the immigrant narrative endures as the most legible depiction of the Asian American experience. You’ve heard this one before: the first generation struggles (but mostly successfully), the next one triumphs (but mostly ambivalently, with not a few pungent lunchbox casualties). On TV and in our book clubs, we now have what can feel like such an embarrassment of this genre of Asian American storytelling that we are right to grow a little weary; it feels at times like we’ve been assimilating forever. Isn’t there more to the story?

Still, I find these narratives worthy of both our examination and a certain deal of luxuriation. If we are to understand Asian American culture as a complex, often self-contradictory project now reaching a kind of coming-of-age of its own over the past few decades, one day, it will make sense why we were first so preoccupied with these origin stories. Visibility is a tricky thing to value—you can roll your eyes at it, confuse your personal ascent with it, trot it out in boardrooms for a variety of suspect agendas—but you can’t ignore its role as a lightning rod for our sense of connective survival.

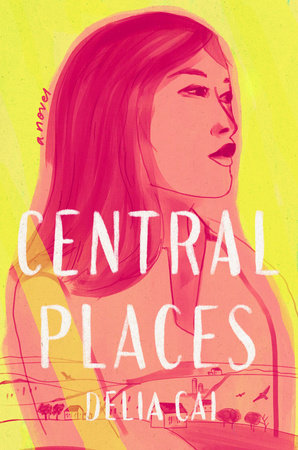

Central Places is a novel about a young woman on a return visit home to her Chinese immigrant family in midwestern America, where isolation is both a fact of life and a self-protective measure. It’s a story about the divide that exists in a first-generation family, but also between the life you might be given and the life you think you want. The following 12 books have been instrumental to this novel’s construction; I’m listing them here roughly in order of thematic life stages at play. Of course, this list leans heavily upon my personal biases toward Chinese characters, New Yorkian settings, mommy issues galore, and the general concerns of any unmarried woman considering how best to shape the chosen family to come. I hope you find them as much of a lifeline as I have.

Sour Heart by Jenny Zhang

Across seven interlinking stories of girlhood set in Flushing, New York, in the ’90s, Zhang shines an industrial-grade UV light on all of those weird parts of growing up that you’d rather not think about. When I first read Sour Heart, it felt like letting myself gorge on something deliciously rancid. Zhang gets the specificity of certain relationships just right: the rivalries between the other ABC (American-born Chinese) girls you’re supposed to identify with, the ambivalence toward reappearing grandparents, the retroactive guilt unearthed, years later, of letting your little brother down.

Beautiful Country by Qian Julie Wang

Wang’s memoir of the years her family spent living undocumented in Chinatown, New York, is an astounding portrayal of a childhood assembled amidst the most precarious circumstances imaginable. Honestly, it’s a painful book to read, particularly for the attentiveness with which Wang slices and separates each disappointment that her young self experienced as a fact of life. But there’s something enormously healing in the opportunity for vicarious excavation that Beautiful Country offers; to review the chaos of immigration and poverty through a child’s eyes is to consider perhaps more gently the general state of confusion that many of us have held within ourselves all these years, too.

Brown Girls by Daphne Palasi Andreades

The main character of Andreades’ lyrical ode to Queens is not one single person, but a royal we that fashions together a kind of glorious sisterhood unsung. Across the novel, we follow a cohort of girls hailing from a mix of outer borough Pakistani, Guyanese, Haitian, Filipino, and Chinese families as they navigate the requisite stages of brown girl teenagery: the classroom microaggressions, the college admissions, that first drink, those alluring flirtations from the so-called other side of the track. Relayed with exquisitely vernacular girltalk and call-outs to the take-out joints/discount stores/subway lines that make a life, Brown Girls is a perfect snapshot of coming up in one beautifully specific time and place.

Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So

From this collection of Californian Cambodian American stories, the one that’s stuck with me the most is “Human Development,” where a disaffected Stanford grad strikes up a situationship with an older, richer Grindr match who is preoccupied with their shared roots. This being set in Silicon Valley, the older guy, Ben, has an idea for an app that would boil down the ever-present minority’s challenge of finding one’s people into a codeable, swipeable solution. Uber, but for your place in the diaspora! This is what So’s stories are so good at in general: pitting the illusion of the clean, autonomous choices of an educated second-gen adulthood against the knotted tapestry that’s impossible from which to ever pull oneself entirely free.

The Namesake by Jhumpa Lahiri

I’m a sucker for intergenerational stories, and Lahiri’s rather comprehensive yarn following a Bengali couple’s immigration to Cambridge, Massachusetts, through to their son’s coming of age is deservedly one of the greats (though I recommend a quick brushing up on the Russian author Nikolai Gogol’s Wikipedia page beforehand if you’re reading for the first time and want the full experience). Of course The Namesake is a story about family, but I love how Lahiri particularly hones in on the mechanism of marriage— how it can both hold everything you know together while also offering a way out.

Chemistry by Weike Wang

Speaking of marriage: in Wang’s wonderfully wry novel, a proposal of engagement weighs heavily on a young grad student as she considers whether or not to follow through with the predominant arc of her life toward fulfilling expectations. Sciencey metaphors about blowing things up abound, but Wang writes the narrator’s inner monologuing almost like these perfect little punchlines. Who knew quarter-life crises could be so funny?

The Groom Will Keep His Name by Matt Ortile

Inextricable from the question of identity is the matter of sex: who are you attracted to and why? What myths have you been told about your desires—and which beliefs do you still carry? This essay collection mulls over the overlapping of internalized colonialism, exoticization, and masculinity against the reality of dating apps and DTRs. Ortile renders his personal encounters with the white male gaze and his ensuing consciousness of self in such earnest prose that you yourself will feel every fiber of those early twenties come rushing back, too.

Crying in H-Mart by Michelle Zauner

Fans of Zauner’s musical talent by way of Japanese Breakfast are no stranger to the artistic irony—or perhaps transcendence is the word here—of the musician’s professional breakthrough following the death of her mother. Crying in H-Mart tells the full story of Zauner’s complicated relationship with her Korean mother using the full extent of a songwriter’s prowess for evocative imagery: I’ll be thinking about that scene where Zauner’s mother breaks in those cowboy boots for her by wearing them around the house for a long, long time.

Severance by Ling Ma

The global pandemic at the center of Ma’s literary version of a zombie movie is one that inflicts upon its victims some seriously deadly consequences of too much nostalgia. New York is caving in from the fictional Shen Fever, but for our protagonist, Candace Chen, her world kind of already ended with the recent passing of her parents. So Candace divides her time in the apocalyptic wreckage between tending to her pointless corporate job and trying to document the strangeness of being (or at least feeling like you are) one of the last people left. Come for Ma’s unsettling pre-COVID foresight, stay for the plentiful uneasy reconciliations with the past.

All This Could Be Different by Sarah Thankam Mathews

I always knew I was going to love Mathews’ novel about a cynical young woman living in Milwaukee juggling millennial post-grad woes and international family obligations, but this book especially dazzles as a sociopolitical parable for the post-Recession generation. The immigrant narrative is inevitably one about filial piety, but Mathews pushes both her protagonist, Sneha, as well as the reader to have greater ambitions about the kind of bonds we could form with our communities at large. Sneha and Tig’s friendship is particularly beautifully drawn, warts and all; would that we all regularly found such extraordinary models of connection in life and in fiction.

Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong

There’s a reason this book has been everywhere, and my theory is that, particularly amongst Azn girl circles, Minor Feelings offers a litmus test for the shape of your own identity politics. It’s part memoir, part cultural criticism, and packed with observations like “Does any Asian American narrative always have to return to the mother?” or the shockingly articulated thought that all our faces look “like God started pinching out your features and then abandoned you.” You’re not not going to have a reaction! More broadly, I also found Minor Feelings helpful in situating oneself within the broader history of Asian American artistry, particularly with the life and work of Theresa Hak Kyung Cha. You always need to know who came before…

The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan

…which brings us to the 1989 novel that, in my view, endures as one of the original texts of the mainstream Asian American immigrant narrative tradition: The Joy Luck Club. When I first read this book in college, I was too distracted to keep track of a storyline that involved four sets of Chinese mothers and daughters; recently, I sat down with it again and deeply enjoyed the read. On one hand, it’s kind of fascinating to realize how tropey so much of the book feels now—it’s basically portrait of a Tiger Mom, complete with the childhood chess team pressures and phonetically spelled pinyin to boot—but the heart of it holds up. I got my mom to start reading it over the holidays, with a pro tip (Amy Tan, I’m sorry if this is sacrilege): instead of reading each chapter in order, start with the first mother-daughter pair’s stories and finish those before working your way to the next one. That’ll help keep all the backstories straight, although I can’t help but wonder if maybe that’s the point—that all these mothers and daughters are supposed to blur together after a while.