I relish the fact that our most celebrated living writers are women.

There are of course the constant evocations of JMG Le Clezio, the Franco-Mauritian winner of the 2008 Nobel Prize in Literature. It is also true that the literary history we are taught is dominated by names such as Marcel Cabon, Malcolm de Chazal, Robert Edouard Hart, Savinien Meredac.

But the Mauritian writers in my home, the ones my friends were (and are still) excited about? The authors that are garnered with global awards and praise? Nathacha Appanah, Ananda Devi, Lindsey Collen, Shenaz Patel, and—though they are lesser known today, unfortunately—Marie-Therese Humbert and Renee Asgarally. These women didn’t just carve out a space for themselves in a deeply patriarchal island: they cut into the heart of the country with their hard, coruscating brilliance. It is impossible to understand Mauritius as it was and is today without reading their work.

While researching this piece, I came across other writers who, although lauded in their time, are forgotten today: their books are out of print, stored in archives. They do have historical and literary interest, though, so I’ve included them. It’s important to note, too, that none of the last five writers in this list has work that has been translated into English (or translated work that has survived, at any rate).

Nathacha Appanah

Nathacha Appanah’s novels are poised, brutal, tender. The Last Brother, translated by Geoffrey Strachan, is a coming-of-age novel set in World War II Mauritius. Raj, a nine-year-old boy from Beau Bassin, meets and befriends David, one of the 1500 or so Jewish refugees kept in the town prison during the war (this really happened, by the way). Both children strike a swift, intense friendship. The much-lauded Tropic of Violence (also beautifully translated by Strachan) is about Moïse, the abandoned son of a refugee from The Comoros, who must fend for himself in Mayotte, a French colony in the Indian Ocean.

Lindsey Collen

A firebrand of devastating talent, Collen won the regional 1994 and 2005 Commonwealth Writers’ Prize for The Rape of Sita and Boy. She was born in South Africa in 1948 and has lived in Mauritius since 1974. In both countries, she has been repeatedly arrested for her work as an activist. She is a member of Lalit, a left-wing political party that advocates for feminism, environmentalism and anti-capitalism, and which has produced an incredible amount of texts for these causes and on the Kreol language (including a dictionary).

The Rape of Sita is a banned book in Mauritius. I haven’t seen her other novels sold in the usual places around the island either (though strangely enough, the National Library of Mauritius apparently does have a copy of the book in their stacks). I urge you to read it: a brilliant, complex, darkly comic, story of rape and oppression. Collen’s talent in this novel reminds me of Salman Rushdie at his best (and as you may have guessed, The Satanic Verses is also banned in Mauritius).

Ananda Devi

“Too violent” is what Mauritians often say about Devi’s work, but probe a little more and they’ll often say “violent and true”. No one blasts the whole notion of “paradise island” like Devi, Mauritius’ greatest literary stylist, whose slim novels are capable of haunting you for years (if not for the rest of your life). She has won many Francophone awards and some of her novels and stories have been translated into English. Her novel Eve Out of Her Ruins, translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman, is narrated by four Mauritian teenagers in Port-Louis caught in a cycle of poverty and destruction.

Just look at these opening lines:

“I am Saadiq. Everybody calls me Saad.

Between despair and cruelty the line is thin.

Eve is my fate, but she claims not to know it.When she bumps into me, her gaze passes through me without stopping. I disappear.”

Shenaz Patel

Shenaz Patel and Lindsey Collen are undoubtedly the most important—and active!—writers living in Mauritius at the moment. Before reading and seeing her much lauded novels and plays, I read Patel’s work in Mauritian newspapers: her pieces were always exacting, investigative and correct. Her literary projects are similarly excellent, and I’m glad that her work is being translated into English. Silence of the Chagos, translated by Jeffrey Zuckerman, is a gorgeous, poignant story based on the uprooting and forced exile of the Chagossian people by the U.S. military and British government.

Priya Hein

Priya Hein is a successful children’s book author, with stories published in English, French, Kreol, and German (I have the delightful Blue Bear at home, which teaches children about respect). In 2014 she published Under the Flamboyant Tree with La Librairie Mauricienne, a collection of traditional Mauritian stories passed down from generations. Her manuscript, Riambel, has won the Prix Jean Fanchette in Mauritius this year.

Natasha Soobramanien

Native Londoner Natasha Soobramanien tapped into her Mauritian heritage to write her prize-winning debut Genie and Paul—a postcolonial retelling of Bernardin de Saint Pierre’s Paul et Virginie—about a sister who travels from the UK to her birthplace in the Indian Ocean to find her missing brother.

Her forthcoming novel Diego Garcia, written in collaboration with Luke Williams, will publish in May 2022. I’m very excited about this one: it’s about the anxieties of sharing a story that’s not your own to tell, but more importantly, about the collaborative fictions authored by the American and British governments to diposess the Chagos Islanders of their home.

Saradha Soobrayen

Born in London to family of Mauritian descent, Soobrayen is an award-winning poet whose work has been anthologized in several publications, most recently in Stairs and Whispers: D/Deaf and Disabled Poets Write Back. She has greatly involved herself in producing art and raising awareness for the Chagossian cause, and describes herself as a creative activist.

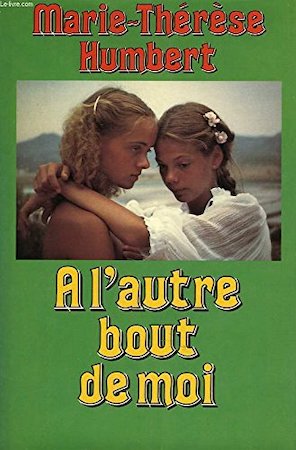

Marie-Thérèse Humbert

Marie-Therese Humbert studied comparative literature at Cambridge and the Sorbonne, and has lived in France since 1968. To put this kind of education in context: in the early 1940s when Humbert was born, girls were excluded from formal education; when schools for girls eventually opened in the 1950s, they were almost exclusively reserved for wealthy, white students.

A L’Autre Bout de Moi, her most famous work (and her debut!) must have sent absolute shockwaves through Mauritius when it was published in 1979. I only read it rather recently and was amazed at its direct, agonizing portrayal of racism on the island. Anne and Nadege, the novel’s protagonists, suffocate under the strictures and structures of racism. The twins are “gens de couleur:” barely bourgeois, light-skinned but not white, with hush-hush African and/or Indian ancestor(s). Anne and Nadege’s parents are desperate to keep up appearances:

“they appraised their gestures, they counted their steps, they assessed, with mute concern, their degree of métissage. Sometimes this was enough to fill up their lives!”

But of course, all their hard work won’t keep the family from rupturing. The novel won the Grand Prix litteraire des lectrices de ELLE in 1980. Even with the foreign accolades and prestigious publisher, the book—and her other novels, in fact—aren’t easy to find in Mauritius. Remarkably, too, A L’Autre Bout de Moi doesn’t seem to have been translated into English yet.

Marcelle Lagesse

Born in 1916, Lagesse was a highly prolific writer despite having no formal education whatsoever. Her life is fascinating: I’m on the lookout for the manuscript of her memoir, in fact.

Lagesse was raised by her grandparents: her mother died when she was three from the Spanish flu, and her father left her in Mauritius to work as an administrator on the Salomon islands (part of the Chagos archipelago). She married her husband at 17, and when he died five years later she moved to the Salomon islands to live with her father and his new family. World War 2 broke a year upon her arrival; she moved back to Mauritius in 1942, when she started writing and publishing seriously. She wrote a good deal of historical fiction and a number of her novels garnered Francophone awards; she also published plays and historical tracts and worked as a journalist.

I only own one book of hers: Cette maison pleine de fantômes, which my husband was assigned to read at school. It was serialized in a newspaper from 1962-1963. Written in the first person, it follows the recollections of Marie-Francoise Lehelle, whose father was the director of the military arsenal found in Turtle Bay. She unofficially keeps the arsenal’s accounts and surveys the operations, a role she keeps even after his death; her brother, who becomes head of the family, is more interested in the pleasures of white society. Though her life is duty-bound and stale, all changes when she meets an Englishman.

Magda Mamet

Born in 1916, Magda Mamet was a Franco-Mauritian poet who lived and died in the vibrant commercial town of Rose Hill. She studied at the Sorbonne and worked as a literary critic for a racist white-run newspaper here. I hadn’t heard of her before I started writing and researching this piece; her work isn’t sold anywhere, and can only be found in the National Library of Mauritius and the Institut Francais de Maurice.

Her most famous work is Cratères, a collection of free-verse poems that won the Prix France-Île Maurice in 1954. They are very much concerned with Catholicism and the human soul; you’d be forgiven for thinking that they weren’t even written in Mauritius, if it weren’t for the constant references to our astringent sun and harsh light. She was hailed a poet of social inequality, but her poems about beggars seemed quite condescending to me: as if, even in real life, they only existed as symbols.

Renee Asgarally

Renee Asgarally made Mauritian history by being the first female Mauritian author to write in Kreol with her début Quand montagne prend difé. Again, some context: Kreol—our national language spoken by most Mauritians—has only been taught as a subject in primary schools since 2012, and Kreol is still not officially spoken by MPs in the National Assembly. Our language was (and is still sometimes) often disparaged, considered inferior to English and French. To publish literature in Kreol in the late 1970s would have been considered scandalous and a mark of bad taste—which makes Asgarally even more formidable, obviously.

Beyond the language, the novel’s subject matter would also have riled Mauritians up: the protagonists, Soonil and Caroline, are forced to keep their relationship a secret since their interracial and interfaith love is forbidden. Nothing ends well (unlike, thankfully, Asgarally’s own happy interracial marriage).

Her work, alongside other Mauritian writers at the time, paved the way for Mauritius’ post-independence linguistic and cultural identity. She continued to publish in Kreol with Tension gagne corne in 1979, and also wrote novels in French. It is shameful to note that I have only found Asgarally’s work in the National Library of Mauritius and the Institut Francais de Maurice.

Raymonde de Kervern

De Kervern is possibly the first woman writer of the island. Her poetry earned her the Prix de La Langue Francaise in 1949 and the Prix d’Académie in 1952. Most (if not all) of her work was gathered into a book (Oeuvres Completes) and published by La Librairie Mauricienne in 2014. Little is known about her: she was a white Franco-Mauritian woman who was born in 1899 and who died 74 years later. Her father was a doctor of local eminence. She was elected for life as the President of Mauritian writers in 1950 and emigrated to France at some point.

From her poetry, I gather that she had a clear interest in mythology, the Bible, Europe, dancers, nature, women. She didn’t write exclusively about Mauritius. Her verse is heady, physical, with a Romantic sensibility. I wonder how some of her more physical poems were received here, if they caused any outrage.

She did have some talent, take some of these lines from Raz de Marée:

“Ah! What is this voice?

It is the deep swell,

Lilac scrolls under the nervous sun

The Indian Ocean, hissing like fire

Twists and circles under the wind of the World.”

Some of her poems are racist. In Aspara La Danseuse, for instance, she creates an excruciatingly Orientalist image of the “Indian dancer”; Aspara is fetishized, turned into a symbol of the “mysteries and wisdom of the East”:

“your dance is sin

under your intimate veils

your wide bronze eyes

lead to the abyss.”

It’s almost as if her verse expresses a longing for the indentured Indian women she saw toiling in the fields of Mauritius (some of these women would also undoubtedly have worked at her home) and who are mentioned later on in the poem:

“on their slender arms

the sweet water of the wells,

Chaste, their eyes lowered,

shadowed by fatigue.”