Many of my experiences in the Marines were equally as ugly and terrifying as a classic gothic haunted house. My book studies some of the parallels between gothic horror and the absurd terror of Operation Enduring Freedom, but The Militia House focuses on the experience of one individual. As I read other veteran writers, I encounter narratives that are different from mine yet just as terrifying in their own ways. The US military is a scary place, especially so for those of us who’ve borne witness to the realities of it.

Veterans who share stories through vulnerable and authentic writing will obliterate the propaganda and bold-faced lies that get us into war, an act of patriotism by my estimation. The following list includes writers whose books break the standard of sanitized, routine portrayals of life and war in the US military. Their work faces the truth head on. While some of these books help the reader understand or reflect, and others inundate with unforgettable, haunting images in order to allow the reader’s interpretation, they all demonstrate that scary is not exclusive to horror or combat.

The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford

Gustav Hasford’s absurd and surreal novel, The Short-Timers, is terrifying between the nauseating violence and the voice of the narrator, Joker, whose ironic and sarcastic responses to atrocity will contrast sharply with the reader’s reaction, hence his nickname. The novel sees Joker, a United States Marine Corps combat correspondent, and his photographer, Rafter Man, roaming an urban battle in the city of Hue as they search for propaganda for the military newspaper. Along the way, they encounter unspeakably horrific scenes and unspeakably horrific people. Hasford punctuates the insanity of the Vietnam War by blurring reality with satire and even genre, sprinkling all kinds of surreal and exaggerated details throughout the book including a literal vampire in one scene. Hasford attended Clarion and was pressured to cut the werewolves in an early draft, but a trace of them remains in the form of haunting figurative language.

Unbecoming: A Memoir of Disobedience by Anuradha Bhagwati

Unbecoming scares me because of the military’s willingness to turn its back on those who directly serve its best interests as leaders. If this is the precedent, then no one is safe. Anuradha Bhagwati demonstrates in her incisive, pointed memoir, that those in designated leadership positions can still be helpless in the face of longstanding misogynistic tradition and bureaucratic negligence. Bhagwati was nowhere near the bottom of the military hierarchy, but she describes scenarios in which she, as a commissioned officer who more than earned her rank in the Marines, is still disregarded for her gender, her sexuality, and even her ethnicity.

Unbecoming tells the story of a Marine Corps officer who finds loneliness, abandonment, and abuse within a community typically joined by people in search of purpose and belonging. The second half of Bhagwati’s book details her post-service efforts to better integrate women into the 21st-century military and to hold military leadership accountable for the widespread military sexual trauma endured by many veterans.

No-No Boy by John Okada

The term “no-no boy” was a pejorative for Japanese American men interned by the United States during World War II who did not forswear allegiance to the Emperor of Japan or agree to volunteer for military service against Imperial Japan. Not only were these men charged with crimes and further imprisoned beyond internment, they were largely ostracized post-war by the Japanese American community.

John Okada, who did in fact serve in the US Army Air Forces during the war, tells the story of Ichiro Yamada, who returns home from imprisonment after refusing to serve the federal government. The novel details Ichiro’s attempts at re-integrating into daily life while maintaining his relationships with family and friends, including his friend Kenji who did elect to serve in the military. Okada’s compassionate, but desolate and tragic novel, studies the consequences of Ichiro’s refusal to serve in the US military as someone who was never fully accepted by the U.S. to begin with.

Cherry by Nico Walker

Cherry is an upsetting novel with a lot going on, to say the least. Nico Walker was implored to write Cherry before his release from prison, and large swaths of violent imagery are transferred directly from the original BuzzFeed article that brought his true life story as a traumatized, heroin-addicted bank robber to public prominence. The section in Iraq portrays violence in vivid detail inflicted by an enemy whom the narrator never sees. The substance of Cherry, from beginning to end, is bleak and terrifying, but what I find structurally intriguing is that the narrator’s experience as a medic in the US Army feels limited mostly to the second act, bookended by substantial non-military sequences of his life. Many war stories are told in a vacuum, but Cherry portrays the reach that the US military can have on someone’s life not only during their service, but before and after.

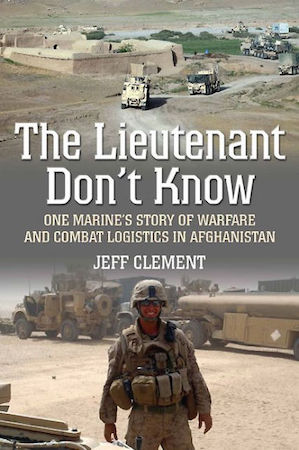

The Lieutenant Don’t Know by Jeff Clement

Jeff Clement’s The Lieutenant Don’t Know partially covers the exact deployment that inspired The Militia House, as he and I were members of the same battalion, but in different companies and performing dramatically different roles.

At times, Clement’s book feels less like a memoir and more like reporting based on the detailed notes he took in 2010, but the book resonates in moments when Clement describes the ambiguous big picture of Operation Enduring Freedom in the Helmand Province of Afghanistan and the confusion many of us felt about the end goal. He calls out higher leadership for protocols that are inefficient or frankly a hindrance to completing a mission, and calls out his own peers who can’t be bothered to take a real life war more seriously than a civilian day job. Clement knows more than he thinks, otherwise I would not have chosen a sentence from his book as one of the epigraphs for my debut novel.

Love My Rifle More Than You by Kayla Williams

For a candid (read: brutally honest) experience of a young woman enlisted in the US Army, this is your book. Williams, a linguist who studied Arabic at Defense Language Institute, shares a range of stories about her time in the Army. Rather than summarizing from a zoomed-out perspective, she relays her experiences through intricate, intimate scenes.

Her own sergeants sometimes move beyond incompetent to being brazenly disrespectful to their subordinates. Her male peers seem to make innocuous small talk, but then close out these interactions by hinting at a sexual proposition or bluntly speaking them. Most disturbing early on: a lieutenant overseeing the search of a monastery, who refuses to interact directly with an English-speaking monk in Iraq, forcing Williams awkwardly to translate between two people who can see, hear, and understand each other. Love My Rifle More Than You does an excellent job of highlighting scenes and mindsets that are effectively terrifying in their implications.

The White Donkey by Maximilian Uriarte

The most affecting book on this list is the only graphic novel and the only infantry-based entry. Maximilian Uriarte served as a grunt in the Marines and deployed to Iraq twice, returning to create Terminal Lance, a hilarious comic strip very specific to daily Marine Corps life from the enlisted perspective.

The White Donkey feels like a book-length culmination of Uriarte’s early work, retaining the same brand of humor while centering Abe (from the comic strip) in an extended narrative that follows an infantry unit throughout their deployment to Iraq. The humor of The White Donkey draws in the reader by building a fondness for the characters. Uriarte then juxtaposes, to maximum effect, our laughter against our reactions to the terrible events that unfold overseas. Uriarte’s candor and vulnerability turn what initially seems like a simple cartoon into a terrifying, but poignant tale of the Global War on Terror.