I love it when a text centers the dynamics of conversation. In my own life, talking to others gets me out of my head, and introduces me to possibilities I would never have dreamed of alone. I think of a quote by the activist Valerie Kaur, which my local bookshop has printed on some of its merchandise: “You are a part of me I do not yet know.” That’s exactly what a good conversation can feel like, for me: like a way of re-integrating and making peace with the other; a reminder that I need their experiences to complete my own.

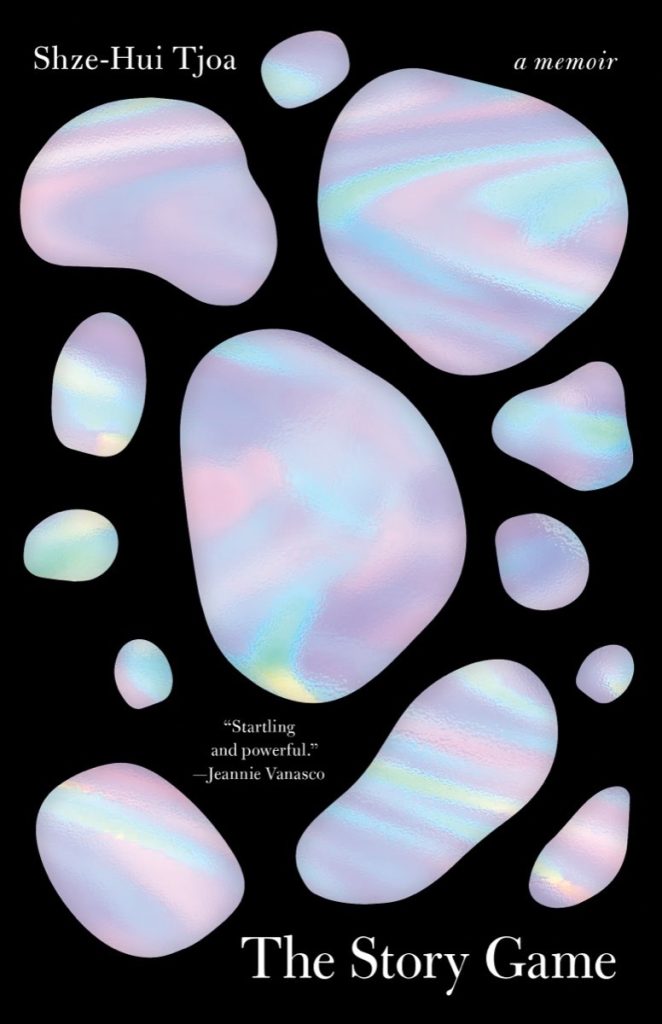

In my memoir The Story Game, a woman named Hui lies on the floor of a dark, eucalyptus-scented room, telling stories about her life to her younger sister, Nin. In between, the two carry on an extended conversation where Nin challenges Hui to dig even deeper—until she can broach the complex-PTSD that she’s suffering from, and uncover lost secrets from her childhood in Singapore.

Conducting (and writing down) this book-length conversation was the most difficult part of my journey as a memoirist! But it was also the part that most profoundly transformed me—not only as a writer, but as a sister and human being. In that vein, here are seven other books I would recommend, which spotlight the pleasures and power of conversation:

Things We Didn’t Talk About When I Was a Girl by Jeannie Vanasco

In this courageous memoir, Vanasco interviews the man who raped her fourteen years ago when they were in high school. She transcribes their conversations verbatim, then dissects them with her partner, close friends and therapist—reflecting on what she said or held back, even specific words or tenses she defaulted to, and what they reveal about her relationships to gender and authority.

I love how this book explores boundaries, control and consent, reminding us that conversations represent an ever-shifting power balance between their participants. Also, I’m drawn to the multiple layers of honesty at work: Vanasco presenting the conversations as they happened, and then openly admitting what she wishes she had said or done differently. (At one point she writes, “I’m too embarrassed to share this transcript with anyone, which is why I should share it.”) What a bold choice to let us into her emotions in real-time, even as she’s figuring them out.

Keeping the House by Tice Cin

This novel follows three generations of women involved in the undercover heroin trade in early-2000s North London. Cin puts a buzzy spin on the subject through her vignettes of the local Turkish Cypriot community—particularly their multilingual conversations full of backchat and wit.

Mostly, Cin styles the novel’s conversations like dialogue in a play script, with limited exposition between lines. This preserves the authentic rhythms of characters’ speech; and whenever they switch to Turkish or Turkish Cypriot, the translations are scattered around the margins like spontaneous annotations. Overall, the book reads like London sounds—electric, polyglottal and chaotic, but always overwhelmingly alive. As someone who grew up speaking a creole language too, I appreciate how Cin’s formal choices do away with the unhelpful boundaries between “proper” and “other” language.

Several People are Typing by Calvin Kasulke

This delightful novel is told entirely through Slack messages. It follows the misadventures of Gerald, an office worker who accidentally uploads his consciousness to his company’s Slack workspace while building a spreadsheet about winter coats. Things only get weirder and funnier from there, as Gerald has to convince his colleagues to believe in his predicament and help him escape the system, amidst their usual avalanche of workplace messaging. Also, he has fend off an increasingly sentient and creepy Slackbot that has begun to quote Yeats in its automated messages (“You can head to our wonderful Help Center cannot hold!”), and is plotting to implant its own consciousness into his now-vacant body.

I like how this book captures the hilarious mundanities of corporate conversations: the snarky group chat names; the gifs and emojis; the invite-only channels where people discuss others’ love lives and bitch about their incompetent bosses (while simultaneously worrying that said bosses might be reading their messages). It’s so refreshing to see a writer acknowledge how real people talk on the internet – with multiple exclamation points, all caps yelling, and snappy little “oof”s and “idk”s and “ty”s.

The Magical Language of Others by E. J. Koh

When Koh was 15, her parents moved to Seoul for a lucrative job offer while leaving her and her brother behind in California. This memoir revolves around letters that Koh’s mother sent her over the next seven years, which are scanned alongside Koh’s Korean-to-English translations. In between the letters, narrative chapters recount Koh’s childhood, the intergenerational trauma linking the women in her family, and how abandonment, sacrifice, and magnanimity shape her understanding of love.

I’m intrigued by how this book emphasizes what goes unsaid in any conversation between two people. Koh writes that although her mother sent her a letter a week—which she often wept while reading—she never responded because “the thought of writing her was unbearable”. This same spirit of restraint permeates the memoir as a whole, with Koh often hinting at her feelings in impressionistic vignettes. What isn’t expressed carries as much weight as what is, shaping the depth of feeling between mother and daughter.

I Want to Die But I Want to Eat Tteokbokki by Baek Sehee, translated by Anton Hur

In this memoir, Baek records conversations she had with her psychiatrist while receiving treatment for persistent depressive disorder—which she describes as a “vague state of being not-fine and not-devastated at the same time.” Their chats touch frankly on themes like perfectionism, compulsive lying, self-surveillance, and taking psychiatric medication. I like that this book’s conversations don’t follow a conventional narrative arc from conflict to redemption. Baek doesn’t stand on a pedestal purporting to have found all the answers; in fact the book’s final chapter is ominously titled “Rock Bottom”. The fluctuating way her journey unfolds feels true to life—as does the occasional circularity of her conversations with her therapist. Ultimately, there are no shiny promises that Baek will keep getting better; I appreciate her bravery to admit this to readers.

The Extinction of Irina Rey by Jennifer Croft

The premise of this novel is deliciously twisty. In 2017, a world-renowned author summons eight translators to her house in the Polish forest, ostensibly to work on translating her magnum opus. But then she disappears, leaving them to descend into rivalry, lust, and chaos. Years later one of the translators, Emi, publishes an autofictional work about those weeks – and yet another, Alexis, translates this book from Polish into English, while attempting to use her position to contest its version of events. The result is the madcap novel we are reading. I find it fascinating how Croft depicts the author-translator relationship as a kind of adversarial dialogue, with two people tussling to control the meaning of a text. In Alexis’ translation, Emi comes across as self-obsessed, petty, and paranoid. But just how far can we trust Alexis, who herself comes across as somewhat cruel and withering in her footnotes? (“Just wow”; “This is so crazy”; “Literally no one alleged this other than her (and she is insane).”) In this novel, translation is a way of speaking back against the dominion of the author – turning what could have been a soliloquy from on high into an intriguing two-way dialogue.

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

This novel is structured as a series of journal entries that Piranesi, the protagonist, writes while wandering alone through a seemingly endless house. He assumes he has always lived in this labyrinthine house; that its infinite halls containing ocean tides, circling birds, and gigantic marble statues constitute the universe. But then, he begins to re-read his old journal entries and the lost memories they contain. And his beliefs about the world that he lives in unravel.

It’s impossible to say more without giving away this novel’s plot! So let me just say that this is one of my all-time favorite books. I admire how it depicts a person conversing with their past self, without glossing over the guts it takes to do this sort of deep emotional work. Having excavated my own lost memories while writing The Story Game, I relate to Piranesi’s journey—how he see-saws between intense curiosity about his past, and an urge to protect himself by looking away. I’ve re-read this book so many times now and the ending always makes me cry.

Read the original article here