How many things can you use a bullet journal for?

Paid work. Creative projects. Household tasks. Grocery shopping. Exercise goals. Meditation routines. Expenses. Glasses of water. The list is endless, with the journal (or journals, for the truly committed) serving as a washi-taped repository of large and small tasks. An archive of a life well spent—or, at the very least, spent.

The impetus behind bullet journals, including my pink notepad with the word “checklist” printed atop each perforated sheet, is to gain a sense of control over what is inherently uncontrollable: life. By tracking what we need, wish and hope to do, we take a stand against unpredictability. We declare, in the face of the unknown, that we will get shit done

But what shit? And why?

Productivity, an economic term that measures the effectiveness of workers by their output, has become an ethical measure for our non-working lives, too. There is an ethos of “usefulness” that permeates contemporary culture, and in our personal lives, this often takes the form of organization. Whether it’s to-do lists, step trackers, meal prep charts, or the behemoth bullet journal pulling everything together, the underlying principle of productivity declares that human lives can and should be organized.

This principle dates back to industrialization. According to Karl Marx, the exploitative condition of factory work meant (and still means) that people were unable to fully inhabit their personhood. With the nature and profits of work removed from people’s control into the hands of a few, factory workers felt alienated from what they did, who they worked with, and ultimately, from themselves.

In today’s neoliberal brand of capitalism, the relentless drive towards getting shit done turns life itself into work. As we check off items on our to-do lists, fill a growing stack of accomplished bullet journals, and strive towards Inbox Zero, we experience an increasing sense of alienation from our lived experience. Or, at least, I do. I feel more legible to myself on paper, on email, on Instagram than I do as a person inhabiting embodied, physical space.

These seven authors know what’s up.

From sleeping away one’s life to orienting ourselves to the rhythms of the nonhuman world, here are some of my favorite books exploring the alienation produced by capitalist society; texts that resist productivity culture at every turn.

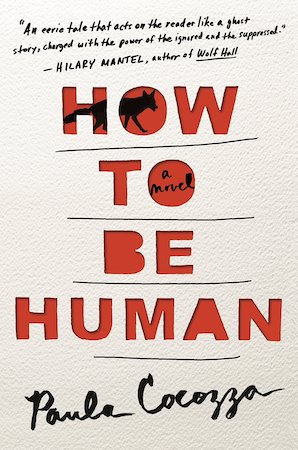

How To Be Human by Paula Cocozza

Mary works for a university department “in shambles,” where she is facing disciplinary action for, among others sins, “entrenched lateness” and “a disappointing attitude.” She feels “herself irresistibly stepping into the footprints of long term failure” (“[i]t was a delusion to think that working in HR…was stimulating”), when she encounters a fox in her London garden. His keen eyes, auburn pelt and unlikely presence capture her attention day after day, especially once he begins bringing what she believes are presents: a pair of boxers, a single gardening glove. As Mary enters into a sustained encounter with this singular creature, the rhythms of her life come loose from the job and life that held her before. How to Be Human is a beautiful novel about the wildness inside each of us. It is also a story of how much exists in the world — even just in our gardens — when HR and the world of work recede from our lives.

There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job by Kikuko Tsumara, translated by Polly Barton

What is an easy job? Suffering from “burnout syndrome”, the unnamed thirty-something narrator of Kikuko Tsumara’s novel There’s No Such Thing As An Easy Job (translated by my favorite Japanese-English translator Polly Barton) embarks on a hesitant quest to find out. She explains:

“I’d left my previous job because it sucked up every scrap of energy I had until there was not a shred left, but…I sensed that hanging around doing nothing forever probably wasn’t the answer either.”

Guided by a surprisingly empathetic recruiter, Tsumara’s narrator accepts a series of entry-level jobs—each with a surreal twist of their own. The Surveillance Job, the Cracker Packet job, the Bus Advertising job, the Postering Job, and the Easy Job in the Hut in the Big Forest comprise little magic realist worlds, woven together by a quiet, awkward woman trying to avoid the devastating psychological effects of a culture devoted to work. I loved this novel so much—perhaps more so because unlike most millennial burnout narratives, Tsumara’s doesn’t have whiteness at its heart.

My Year of Rest and Relaxation by Ottessa Moshfegh

Next to my bed is a scrap of lined paper that reads, “My year of rest and relaxation—Sept 2019” : a testament to the fact that I read Ottessa Moshfegh’s runaway bestseller at the right time. I was very sick that monsoon, and everything I had planned or hoped for the year had fallen apart. So when Moshfegh’s narrator decides to cope with alienation and grief by getting incredibly fucked up on prescription drugs and effectively sleeping away a year, it read to me less like satire and more like a solid plan. At least the part where sleep feels like a reasonable response and resistance to a world that wants you to keep doing things, to keep performing your self without pause.

I almost immediately gave away my copy of My Year of Rest and Relaxation to another chronically sick friend who I thought would also appreciate this determined and deranged pursuit of sleep (she did). Nearly two and a half years after I taped it up in a haze of desperation, that note remains stuck to my bedside wall. A reminder that rest isn’t just a deep tissue massage, but a drastic response to the equally drastic demands made by contemporary culture on our lives.

Orwell’s Roses by Rebecca Solnit

Best known for her feminist work, Rebecca Solnit is, for me, the most compelling living writer on ecology, place and hope. Her work draws attention—both hers and the reader’s—away from the relentlessness of technology and its attendant busyness, and towards the rhythms of human and nonhuman interactions and lives.

In Orwell’s Roses—Solnit’s book on George Orwell, gardening, refuge, and resistance—we encounter the vast timescale of trees, mutual aid as “inter-species cooperation”, and an Orwell whose pleasures in the natural world informed his resistance to control and power. Just as 18th-century labor struggles advocated “Bread for all, and roses too,” Solnit writes, “you could argue that any or every evasion of quantifiability and commodifiability is a victory against assembly lines [and] authorities.” Productivity culture is built on quantifying output, tasks and time —and like much of her writing, Solnit’s newest book serves as both antidote and balm.

Earthlings by Sayaka Murata, translated by Ginny Tapley Takemori

“I was a tool for the town’s good, in two senses. Firstly, I had to study hard to become a work tool. Secondly, I had to be a good girl, so that I could become a reproductive organ for the town. I would probably be a failure on both counts…”

Natsuki, the narrator of Earthlings has spent life with her head down, trying to slip by unnoticed in a society that demands from her roles of productivity she cannot fulfill. Spanning childhood summers with her cousin Yuu — with whom Natsuki dreamt of a spaceship coming to take them to their “real” home — and an adulthood living with buried trauma, Earthlings is Murata at her trademark best: a radical, surreal excavation of society’s unquestioned structures and their impact on people unable to fit in. As children, Yuu and Natsuki make a pact: “Survive, no matter what.” In a system that sees individuals as tools, as means to an end, what shapes can survival take? And what happens when people stop trying to pass as acceptable, productive earthlings?

Bird Cottage by Eva Meijer, translated by Antoinette Fawcett

In 1937, at 40-years-old, Len Howard left her city life and career as a violinist in an orchestra to study birds. She moved to a small cottage in the South of England where she lived the rest of her long life alongside a variety of birds: Great Tits, Magpies, Blackbirds, Sparrows.

Bird Cottage, Eva Meijers’s fictionalized account of Howard’s life, may not seem like a resistance to productivity culture at first glance. But as Meijer skillfully intersperses her narrator’s rejection of the life she was trained for with the real Howard’s observations of the birds she loved (these were among the first non-lab studies of birds conducted and widely declared unscientific at the time), the reader, too, is asked to retrain their eyes and attention: to look away from what we “should” do towards beings who are indifferent to our ideas of timekeeping and success. The birds that visit my garden were infinitely more alive as I read Bird Cottage — a redirecting of my attention so complete that I’m sure I will return to this graceful, charming novel time and again.

How To Do Nothing: Resisting the Attention Economy by Jenny Odell

Speaking of returning to a book as a means to redirecting my attention, a friend recently wondered if I’d ever write an essay that didn’t quote Jenny Odell (as it stands, that seems unlikely). No book has influenced me so deeply as How To Do Nothing, which has served, among myriad purposes, as a guide to disentangling myself from my Type A personality (a direction my chronically sick body very much appreciates).

Through her text that spans “surviving” a culture of usefulness, the impossibility of retreating to a commune, and a reciprocal relationship with nature, Odell seeks to “draw us… out of a worldview in which everything exists for us.” Productivity, in all its goal-based glory, spins on an axis that holds human advancements and progress at its center. For Odell, what matters instead of constant newness and achievements are as slower acts of restoration—of ecology, context, thought, and our sense of place in the face of the internet’s “placelessness”. How To Do Nothing questions where our endless productivity goals come from, and what might open up in their stead if, as Odell suggests, we responded to them in the words of Melville’s Bartleby: “I would prefer not to.”