If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

It’s a truism that historical fiction reveals more about its own age it than the one it portrays. We can’t escape or even perceive our own biases, the reasoning goes, so we end up helplessly projecting them onto a past where they don’t belong. But the past is not a museum, and contemporary perspectives don’t necessarily distort historical subjects.

And to state the obvious, historical fiction isn’t history. Accuracy and authenticity are not the same things, and “distortion” is a loaded term to begin with. In The Underground Railroad, Colson Whitehead interleaves the archival ephemera of slavery with his own dystopian imaginings. That the two are often indistinguishable shows that narratives need not be strictly historical to be fundamentally truthful. Art is supposed to transfigure human experience, to make it newly meaningful. That’s what it’s always done. That’s what it’s for.

Of course, novelists don’t always begin with such lofty intentions. In writing The House on Vesper Sands, I began with no intentions at all. At the time, though, the U.K.’s Tory government was diligently stripping the vulnerable of what meager protections they depended on. Their souls, I remember thinking to myself. They’re devouring people’s souls. And since I found myself with one foot in Victorian London, where such notions were taken pretty seriously, I began to see new shapes in its familiar gaslit fog.

Fingersmith by Sarah Waters

As important as representation may be, gay characters don’t need to appear in fiction for any particular reason. Waters describes her own sexuality as “incidental,” and in her Victorian England, lesbian women are naturally just present. Like everyone else in Fingersmith, though, they’re also schemers and strivers. Waters renders their erotic encounters with dependable virtuosity, only to use them as a fulcrum for one of the most breathtaking double twists in all of fiction.

The Luminaries by Eleanor Catton

In historical fiction, verisimilitude isn’t always your friend. The line between authenticity and pastiche is vanishingly fine, but although Catton assuredly knows the risks, she bets the farm in this novel anyway. The Luminaries might be compared to an immaculately crafted piece of reproduction furniture, but one whose intricately inlaid surfaces conceal all manner of arcane inscriptions and secret compartments.

The Crimson Petal and the White by Michel Faber

Faber’s revivification of Victorian London is both exquisitely wrought and magnificently coarse. Although his embrace of all social classes invited comparison with Dickens, he has more in common with Chaucer, whose democratic instincts were much less hampered by paternalistic illusions. The only illusions here—as Faber reminds us in sly metafictional interjections—are our own: “You are an alien from another time and place altogether.”

Alias Grace by Margaret Atwood

In Atwood’s best-known fictions, for all their undisputed merits, character is often subservient to some overarching schema of ideas. Based on real events—involving an Irish maid implicated in a brutal double murder—Alias Grace provides a counterpoint in a character study as enthralling as it is forensic. It also demonstrates the necessity of revisiting grim historical realities, like the coercive medicalization of femininity, that have never quite gone away.

Oscar and Lucinda by Peter Carey

Like Eleanor Catton, the Australian novelist Peter Carey shows how Victorian certainties tended to dissolve at the periphery of their empire. When he undertakes to transport Lucinda Leplastrier’s glass church to the remote Outback, inveterate gambler Oscar Hopkins seems to embody Pascal’s conception of religious belief as a momentous wager. The same might be said of this novel’s unlikely but indelible love story, in which everything and nothing may be at stake.

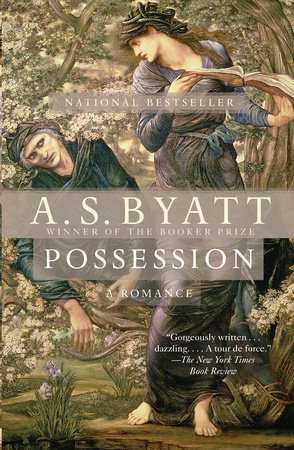

Possession by A. S. Byatt

Byatt might be unlikely to use the term herself, but in Possession she proves that you can be formidably erudite and also, well, extremely meta. True to form, she styles it “a romance” in the strict literary sense—that is, a quest narrative in which defining values are tested. But as its fusty Victorian scholars unearth a love affair between Victorian poets, they discover hesitant passions of their own. Think Inception, but with tweedy academics and polite rapture.

Shadowplay by Joseph O’Connor

Bram Stoker hadn’t written Dracula when he left Ireland for London, but he had begun to feel its dark stirrings. There, he managed the Lyceum Theatre and began a lifelong entanglement with Henry Irving and Ellen Terry, giants both of the Victorian stage and of egotistical excess. In O’Connor’s wholly masterful recreation, we also see him wander the Ripper-haunted streets, contemplating an era in decline and the monsters it might harbor and bequeath.