The 1800s is an intriguing era to explore with fiction. It is not so far in the past as to be unrecognizable to a modern reader. And yet it is removed enough from to present that one will inevitably notice curious differences.

Among the curious yet profound differences in the 19th-century Western world is the prevalence of race-based chattel slavery. It was in this century that the institution of slavery met its end, and millions of people of African descent won the legal freedom of emancipation.

Slavery (and its afterlife) is full of narrative potential: the enslavement of one person by another is perhaps the most fundamental promise of conflict imaginable. It is easy, as a writer of fiction, to be too obvious when navigating such a fraught topic. How to tell a story about a Black 19th-century experience without resorting to uninspired plot choices, tired dialogue, and stereotypical characters?

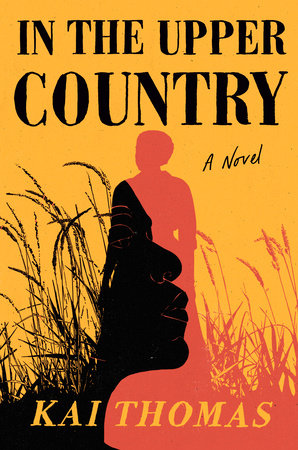

In my own novel, In the Upper Country, I sought to imbue freshness in the genre through a variety of means, for example, by attending to the neglected history of Black and Indigenous relations of the period.

Here are seven other novels about Black folks in the 1800s, and a few words about the unique and astounding ways the authors bring their stories to life.

Conjure Women by Afia Atakora

Atakora offers a fascinating closeup on the worlds of midwifery and conjure before and after Emancipation. Conjure Women is set in a remote and isolated Southern plantation that brims with a dark, gothic mood.

Infectious illness is a central theme of the book, and this deepens the haunting atmosphere. I had a double-take when I saw it was written pre-2020; it has a prophetic quality in that respect. Reading Conjure Women from the era of Covid, one feels a profound bond with the characters as they contend with the emotional effects of social isolation and the ways that illness can infect not only individuals’ bodies but whole communities. Atakora writes with luscious prose and calm pacing, oscillating back and forth in time to deliver an ethereal, vivid tale.

Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

The world of Washington Black is exquisitely immersive. The attention to detail in Edugyan’s prose has a way of slowing down time. It’s like touring an exhibit at an art museum wherein one can amble through the rooms, taking long pauses to pore over the paintings—each a scene.

The novel is a true bildungsroman—one feels the indelible, slow transformation of the protagonist Wash, from his childhood on a Barbados plantation to his career as a scientific illustrator and inventor.

Washington Black brings together two moods: the romance of 19th-century science fiction, and the terror of slavery and its afterlife. It is a remix in hip-hop fashion, and the resulting rhythm is as fresh as it is classic.

Slave Old Man by Patrick Chamoiseau, translated by Linda Coverdale

Chamoiseau recalls the surreal and deeply symbolic works of Ben Okri and Ngugi wa Thiongo in this tale following the journey of an old man off the plantation and into the wilderness of Martinique, pursued by a terrifying slave-hunting mastiff.

It is the kind of book that explodes language (in a good way). Originally written in French and Creole, the English translation by Linda Coverdale is quite successful, especially given the complexity of the prose. It is a novel that does what good poetry does; inviting readers to do some imaginative work as we are confronted with combinations of words that are as strange and unique as they are profoundly beautiful:

“Around him, everything shivered shapeless, vulva dark, carnal opacity, odors of weary eternity and famished life. The forest interior was still in the grip of a millenary night. Like a cocoon of aspirating spittle. Another world.”

Libertie by Kaitlin Greenidge

The novel is unique among the others in this list, in that there are no scenes of enslavement. But despite this “absence,” Greenidge’s story is not missing anything. Libertie is a vibrant coming-of-age that follows the titular character from Civil War-era Brooklyn to Haiti as she wrestles with her sense of purpose in the world.

It is a sublime story of family, nation, and sovereignty. Greenidge’s characters are enduring; peculiar as they are keenly familiar. And indeed it is the characters who carry this story. There are no villains or cliff-hangers to coerce the reader’s attention. It is the rich and particular wonders of the everyday that keep the pages turning.

The Sweetness of Water by Nathan Harris

The Sweetness of Water is an engrossing novel set in rural Georgia in the wake of the Civil War. When an aging white landowner finds two of his neighbor’s erstwhile slaves on his land, they strike up a friendship that throws the entire town into turmoil. The early days of Reconstruction are animated here with Harris’s powerful description.

In many ways, this novel ironically illuminates the Black experience through its white characters. Their struggles and encounters in the world serve as a constant foil to those of the Black characters. It is a subtle effect that makes the story resonate with layers of meaning.

She Would Be King by Wayétu Moore

She Would Be King braids together the stories of three people imbued with supernatural abilities. From Jamaica to Virginia to Liberia, their stories meld the fantastical with the real, yielding poignant and nuanced scenes that shed light on the politics of a unique place and chapter of history.

Moore’s style in this novel recalls Octavia Butler’s Wild Seed without being imitative—She Would be King has a distinctive flair and a setting completely its own. The narrative flows from haunting and brutal scenes of enslavement to beautifully detailed descriptions of a site of colonization not often written about; that of the formerly enslaved Black settler class who set about forming a nation in West Africa.

The Book of Night Women by Marlon James

This book is like a Kara Walker tableau come alive on the page. Narrated in Jamaican Patois, The Book of Night Women follows the coming of age of the protagonist Lilith as she finds herself taking up violent actions in order to survive her existence on the Montpelier estate. From the first page to the last, James relentlessly depicts the utter horror of early 1800s Jamaica plantation culture and the dark vagaries of plantation social order. The violence of James’ work here is harrowing without being gratuitous—the unglorified chaos of enslavement and rebellion is given sobering and disturbing ramifications.