Returning to England after two weeks in Nigeria back in 2019, I found myself marveling at how green the grass on the side of the motorway was. The thing I love about coming home from anywhere, is the moment where you can look at everything with a fresh, often rose-tinted, perspective. Maybe it’s partly “absence makes the heart grow fonder” and partly the fact that distance allows us to drink in the details we would ordinarily overlook, but for a brief time, the familiar suddenly becomes novel.

In literature, homecomings are great because the reader begins on the same page as the narrator or protagonist, walking into the party together, so to speak. A well-written homecoming scene immediately situates a character and reveals a lot about their relationships to the place and people around them. We all come from somewhere, and our connection to that place—or the conspicuous lack of one—can quickly and succinctly, say a lot.

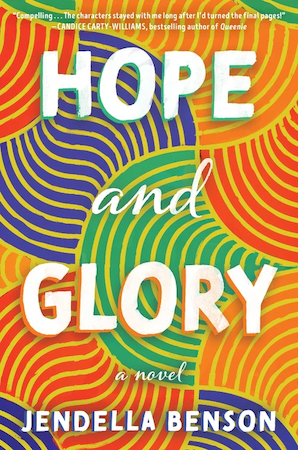

My debut novel, Hope and Glory, starts with a homecoming. Glory has been in Los Angeles where she’s been having the time of her life, if you believe her Instagram feed. When her father suddenly dies, she returns to her hometown of Peckham, South London, where she finds her family in complete disarray. Her brother is in prison, her once-ambitious sister is stuck in a problematic marriage, and her mother is very close to mental breakdown. Her return home is not the triumphant victory lap she once imagined it would be, but it is the beginning of her journey to reconnect with her family and herself.

Another thing that I love about homecomings in literature is that they work across multiple levels. Of course there is the physical return to a place, but it could also be revisiting something on an emotional or psychic level, reconnecting with old friends and enemies, or a re-exploration of the inner self. In my humble opinion, the best homecoming stories are mix of all of the above, and below you’ll find a list of some of my favorites.

Memphis by Tara M. Stringfellow

Memphis is a lush novel that follows three generations of a Black Southern family through tragedy, the civil rights era, loss, estrangement, and reunion. It is a celebration of the bond of women, the resilience of family and the musicality and life of the city of Memphis itself. Tara’s prose is so rich I could almost feel the heat and smell the honeysuckle.

It starts with ten-year-old Joan, her mother and her younger sister returning to the house her grandfather built, escaping their Marine father and a violent home. In Tennessee, they build new lives, chase old dreams and navigate past traumas. Stringfellow writes a coming-of-age story that is filled with love and hope, as much as it challenges the darker side of humanity, and in particular, the harms that men enact on the women in their lives.

26a by Diana Evans

26a is the debut novel of Diana Evans, the author of the critically-acclaimed Ordinary People. It is a layered story that is all at once tragic, warm, humorous and dark.

It begins in the attic room of a residential home in Neasden, North London, where twin sisters Georgia and Bessi weave a fantasy world around themselves. They share their home with older sister Bel, younger sister Kemy, their homesick Nigerian mother and emotionally unavailable English father. The narrative moves to Nigeria, where their mother experiences a long-delayed homecoming of her own, but where her children are introduced to various terrors that will haunt them when they return to England. 26a is the story of a family that is as beautiful as it is heartbreaking.

Sankofa by Chibundu Onuzo

The title of the novel is a Twi word, which literally translates to “go back and get.” It is also the name of an Adinkra symbol, which is used to represent philosophical ideas by the Akan ethnic group, who are primarily found in Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. Sankofa is a fitting title for a novel that follows a middle-aged woman as she returns to a “home” she has never known, in order to “go back and get” an understanding of who she is at a point in her life where all that she has known is fast falling away.

When we meet Anna, she has separated from her husband, her only daughter is an adult who needs her less and less, and her mother has just died. When Anna finds her father’s diary amongst her mother’s possessions, she sets off on a journey to find out more about a man she never knew who left her mother before she was even born. This journey takes her to Bamana, a fictionalized West African country, where she discovers uncomfortable truths about her father and his legacy, but also has the opportunity to connect with a side of her heritage that has been obscured for most of her life.

Black Cake by Charmaine Wilkerson

Charmaine Wilkerson’s bestselling debut novel begins with estranged siblings, Benny and Byron, forced to reunite at the request of their late mother. They return to the house they grew up in to piece together the fragments of a woman they soon realize they didn’t fully know. Through a voice recording delivered by their mother’s lawyer, they unearth a family history filled with secrets and shame that casts their parents in a completely different light. Through this, Benny and Byron are also grappling with the break down of relationships—with lovers, their parents, and each other.

Black Cake is a unique story, written in fragments and multiple perspectives. It covers decades and continents, flying between a community on a Caribbean island living in quiet terror, a postwar Britain as hostile to immigrants as it is desperate for their labor and finally, modern day California. The novel is also rich in thematic significance, with motifs of the ocean and food resurfacing to provide a satisfying circularity to narrative.

The Salt Eaters by Toni Cade Bambara

The Salt Eaters starts in the middle of a healing ritual for Velma Henry, a veteran community activist who suffers a breakdown and attempts to kill herself after becoming disillusioned with her life’s work. The ceremony is overseen by Minnie Ransom, a locally famous healer who is guided through the healing by a “haint” named Old Wife, and witnessed by a variety of characters, many of whom know Velma personally.

This novel is beautifully lyrical and experimental in style, written from numerous points of view, including chapters that feature long dialogues between Minnie and her spirit guide, Old Wife. The politics of 1960s and ’70s feminist, anti-war and civil rights movements are apparent in the narrative, without being overbearing or preachy in tone. Ultimately the book is as much about collective healing as it is about Velma finding her way back to herself.

Looking for Transwonderland: Travels in Nigeria by Noo Saro-Wiwa

Noo Saro-Wiwa is a travel writer and the daughter of famed Nigerian writer and activist Ken Saro-Wiwa. After her father was murdered by Nigeria’s military regime in the ’90s, she stayed away from Nigeria for many years, finally returning as an adult to make sense of the country her father loved and died for.

In Looking for Transwonderland, there is a different sort of homecoming. There is little sentimentality but a clear-eyed look at a country whose greatness has arguably been squandered due to persistent poor governance. Still, it is revealed to be a country that is as beautiful as it is maddening—something that Nigerian nationals, both home and abroad, will readily agree with. So much of modern Nigerian myth revolves around Lagos, the sprawling mega city that is home to The Giant of Africa’s creative industries. But this travelogue reveals the breadth and diversity of a nation in the way only a Nigerian returning from exile can.

Sula by Toni Morrison

While it goes without saying that Toni Morrison was a writer of singular talent and significance, I feel like her second novel often flies under the radar when it comes to evaluations of her work. Sula, for me, is as much a portrait of town and a people, as it is about the titular protagonist and the evolution of her relationship with Nel, her best friend.

Sula and Nel grow up in Bottom, a fictional town up in the hills of Ohio. They both have strained relationships with their mothers; Nel secretly despises her prim and proper mother, while Sula nurses growing contempt her care-free, openly promiscuous one. A secret tragedy that they witness binds the girls even closer together, but as they get older, Nel decides to stay in Bottom, falling willingly into the role of wife and mother, while Sula leaves the town, travelling, attending college and living a life as care-free abroad as her mother did at home. When Sula returns, her presence sends ripples through the town, which will ultimately test her friendship with Nel the most.