I first heard the term “smart women adrift” from my graduate school professor, Sigrid Nunez—herself a master of writing incisive female characters. At the time, the term made me laugh, because it opened an umbrella over a type of literary woman who had long existed, unclassified, in my literary consciousness, and there is something funny about acquiring a new name for an old concept. The term, coined by Katie Roiphe in her 2013 review of Renata Adler’s cult classic novel, Speedboat, describes—in Roiphe’s words—a class of novel that centers around “a damaged, smart woman” who gives voice to “a shrewd and jaded observation of small things, a comic or wry apprehension of life’s absurdities.” Roiphe describes these women as floating “passively yet stylishly…without a stable or conventional family situation,” and conveying “the exhaustion of trying to make sense of things that don’t make sense.”

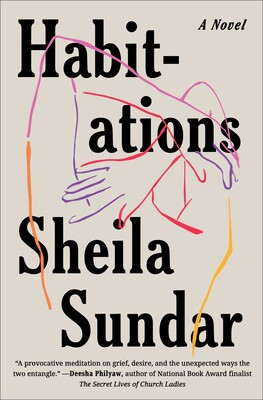

Early in my debut novel, Habitations, my protagonist, Vega Gopalan, a sociologist who was born and raised in India, begins an affair with one of her professors, a Jamaican public health scholar named Winston. To Vega, Winston provides an escape from the loneliness of marriage and motherhood. But their relationship shifts when he asks her to articulate what she wants for her future, advising her to navigate the racial hierarchies of academia by building an ambitious plan for herself. He tells her, “I expect you to think bigger than your life right now.”

As Vega moves from one romantic relationship to another, she is haunted by the loss of a younger sister years prior, and gripped by the conflicting obligations she feels to her family and to herself. She responds by telling Winston, “We can’t all be free to think big. At least, not in a geographic sense.” Inwardly, she reveals, “It was too narrow a response…but it was also the fullest and most encompassing truth she could manage…She didn’t want to spend her life in the confines of her marriage, but it was one thing to imagine a different future, and another to begin the process—the awful, mechanical process—of remaking it.”

When writing Habitations, it did not occur to me that the story would fit within this tradition. The smart women I had read about in books—at least, the women deemed smart in literary discourse—seemed to possess a sturdiness that was acquired only after generations of belonging. Vega was smart, but she was not sure-footed, and her story asks more questions than it answers: How does one escape the shadow of loss? How do we satisfy our dueling needs for love, sex, and freedom? What is the weight of caste, class, and race in America? How does an immigrant, and a cultural outsider, make (and remake) a home in a new country?

The following seven novels capture the lives of smart, immigrant women. Unlike Roiphe’s women, who study the machinery of life from a distance, these protagonists make sense of the world while simultaneously laboring inside of it—a nanny, a bookkeeper, a translator, a doctor, a scientist, an academic. As with all lists, this one is incomplete; there are many other novels that tell the story of women who carry with them, from country to country, a sharp critique of the social, cultural, and economic order even as they find their place within it.

Americanah by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie

In her 2016 article in the New York Times, “Nigeria’s Failed Promises,” Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie wrote, “I was 7 years old the first time I recognized political fear. My parents and their friends were talking about the government, in our living room…Yet they spoke in whispers. So ingrained was their apprehension that they whispered even when they did not need to.” In her novel, Americanah, Adichie’s protagonist, Ifemelu, bears close witness to this political fear. She observes the shrouded language—the military general who purchases her aunt’s sexual servitude is referred to as her “mentor”, and his gifts as “miracles.” She observes the wealth of the military elite and its grip on her country’s public institutions, the manipulations of the church, and the quiet struggle of her middle-class family.

When she comes to the United States, she observes the peculiarity with which race is weaponized and discussed. Early in the book, a white woman—for whom she becomes a nanny—comments on Ifemelu’s name, saying “I love multicultural names because they have such wonderful meanings, from wonderful rich cultures.” Silently, Ifemelu comments that “Kimberly was smiling the kindly smile of people who thought ‘culture’ the unfamiliar reserve of colorful people…She would not think Norway had a ‘rich culture’.” Later, she says of a Black woman she meets at a party, “She said ‘motherland’ and ‘Yoruba religion’ often, glancing at Ifemelu as though for confirmation, and it was a parody of Africa that Ifemelu felt uncomfortable about and then felt bad for feeling so uncomfortable.” Yet she speaks tenderly about her Nigerian American nephew, observing the cutting effect of racism as he comes of age in suburban America. And she speaks to the invisible grip of race on her romantic relationships, first with a white man and then a Black man, assessing, in their aftermath, the limits to what she, herself, could understand.

Patsy by Nicole Dennis-Benn

At the onset of the novel, Patsy leaves behind her five-year-old daughter in search of a mythical life in Brooklyn that does not materialize. The severing of this relationship hurts her daughter and stings the reader, but Patsy reflects, as she makes her choice, on the confluence of circumstances that led to this moment: the inability to access an abortion, the indifference of her daughter’s father, the inadequacy of the educational system in which she came up, and the professional ceiling that obstructs her as she dreams of something bigger.

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

The protagonist, Gifty, tells the story of her Ghanaian immigrant family’s beginnings from a unit of four to a surviving pair of two. When she is young, her homesick father leaves their new life in Huntsville, Alabama, to return to Ghana. Years later her brother Nana, a gifted athlete, dies of a drug-overdose tied directly to his prescription of OxyContin following a sports-related injury. In telling his story, Gifty recounts the conditional reverence he is given as a Black male athlete, and the years of animus that preceded it.

Gifty is raised in her mother’s evangelical church and, as a brilliant child seeking answers to unanswerable questions, she believes fiercely and literally in the tenets of the faith. Later, as a PhD candidate, she attempts to understand the science behind her brother’s addiction. Though she is grounded in her research, she relies on the vestiges of religious belief to explain what science can’t address by itself. In her early years, her migration is determined for her. As an adult, moving from one city and institution to the next, her migration is driven by the pursuit of knowledge and understanding. At the close of the novel, she tells the reader, “The truth is we don’t know what we don’t know. We don’t even know the questions we need to ask in order to find out, but when we learn one tiny little thing, a dim light comes on in a dark hallway, and suddenly a new question appears. We spend decades, centuries, millennia, trying to answer that one question so that another dim light will come on. That’s science, but that’s also everything else, isn’t it?”

Lucy by Jamaica Kincaid

At nineteen years old, Jamaica Kincaid’s Lucy arrives from an unnamed island in the West Indies to work as a nanny for a wealthy couple in an (also unnamed) American city. Her employer, Mariah, is intent upon forming a sisterly relationship with her, though Lucy initially resists these efforts. Raised in a country bound by the legacy of colonialism, by a mother whose greatest ambition for Lucy was to pursue a career in nursing–a gendered path that Lucy reveals she would have hated–she finds Mariah coddled and shallow, a woman unable to imagine a life circumscribed by parameters different from her own.

Throughout the novel, Lucy reflects on the personal and intimate forces of gender and colonialism. Yet when Mariah brings her to a museum to see an exhibit by a painter who the reader is led to believe is Paul Gauguin, she does not see herself in the subjects of Gauguin’s art–the brown-skinned women with whom she shares a colonial past. Instead, she sees her own impulses reflected in Gauguin’s desire to wander. “I identified with the yearnings of this man. I understood finding the place you are born in an unbearable prison and wanting something completely different from what you are familiar with, knowing it represents a haven.”

Intimacies by Katie Kitamura

The reader doesn’t learn much about the map of the unnamed protagonist’s life prior to the start of the novel. We know that she was raised in a Japanese-speaking home, that her father has died and her mother settled in Singapore (a country to which the protagonist has no ties) and that her childhood and adulthood have been migratory. Intimacies is set in The Hague, where she works as a translator for a body that, though also unnamed, appears to represent the International Criminal Court.

As the protagonist examines the moral questions of her work—the power and limits of translation—she drifts between the possibilities of remaining in and leaving The Hague. Her decision is affected in part by an uncertain romance, as well as the broader uncertainty of kinship and human connection. She questions, too, the emotional and psychological toll that her job takes; this examination is a reminder that our intellectual and professional pursuits can reach and reveal the most intimate parts of us—who we are, where we should go, and the imprint we want to have on the world.

Brooklyn by Colm Toibin

Before Brooklyn’s protagonist, Eilis Lacey leaves her home in Ireland shortly after World War II, she accepts part-time work in the town’s grocery store. It’s a miserable job but one of relative privilege and status; she is recruited for the position because she is known to have “a great head for figures”, and the wages help her support her widowed mother.

Later, when she leaves Ireland and settles in Brooklyn, she accepts a position working the floor of a department store. Though initially glamorous, the work quickly becomes dull and monotonous. To stave off her boredom and homesickness, she enrolls in a course in bookkeeping and accounting at Brooklyn College and begins to imagine a life of professional sturdiness and independence.

Eilis seeks opportunity in the farthest reaches her circumstances allow, and her smarts come through in this hunger for learning and labor. She is also a sharp critic of those around her, examining dominant notions of race and gender. But it is her honest examination of herself and her personal desires that makes her most unique. When she briefly returns to Ireland towards the end of the novel, she considers two marriage prospects—one to an Irish man from her hometown, and the other to an Italian American man in Brooklyn. “When she came back from receiving communion, Eilis tried to pray and found herself actually answering the question that she was about to ask in her prayers. The answer was that there was no answer, that nothing she could do would be right. She pictured Tony and Jim opposite each other… each of them smiling, warm, friendly, easygoing, Jim less eager than Tony, less funny, less curious, but more self-contained and more sure of his own place in the world.” Without being fatalistic, the novel considers the limited circumstances of a woman who is choosing between two countries, and two men, and wants more than what is on offer.

Joan is Okay by Weike Wang

Weike Wang’s biting character, Joan, spends the novel in receipt of unsolicited advice. She is pushed by her brother and sister-in-law to marry and have children. She is pushed by a socially aggressive neighbor to be more outgoing. When she travels to China for her father’s funeral and returns to the hospital where she works as an ICU doctor two days later, she is pushed to take additional time off in pursuit of work-life balance.Joan’s resistance to all of this advice—though often hilariously delivered—is not the habit of a grumpy refusenik. She holds deep conviction, and a commitment to medicine that mows down any attempt to diminish her in the one area of her life that matters most. Early in the novel, she tells the reader, “Today someone said that I looked like a mouse. Five six and 290 pounds, he, in a backless gown with nonslip tube socks, said that my looking like a mouse made him wary. He asked how old I was. What schools had I gone to, and were they prestigious?…I told the man that he could try another hospital or come back at another time. But high chance I would still be here and he would still think that I looked like a mouse.” When the Covid-19 pandemic arrives, the novel tells the story not just of a single woman’s dignity, but of the essential nature of her work and her right to a life of her choosing.

Read the original article here