I love books about women who go off the rails. They can be comic or tragic. Either way there’s something serious underfoot. When a woman loses the plot, she has a good reason. She signed a deal and wants to renege. She may suddenly have some serious second thoughts about her entire life. There are many ways to say it, but it basically comes down to this: A woman can no longer abide. The center will not hold.

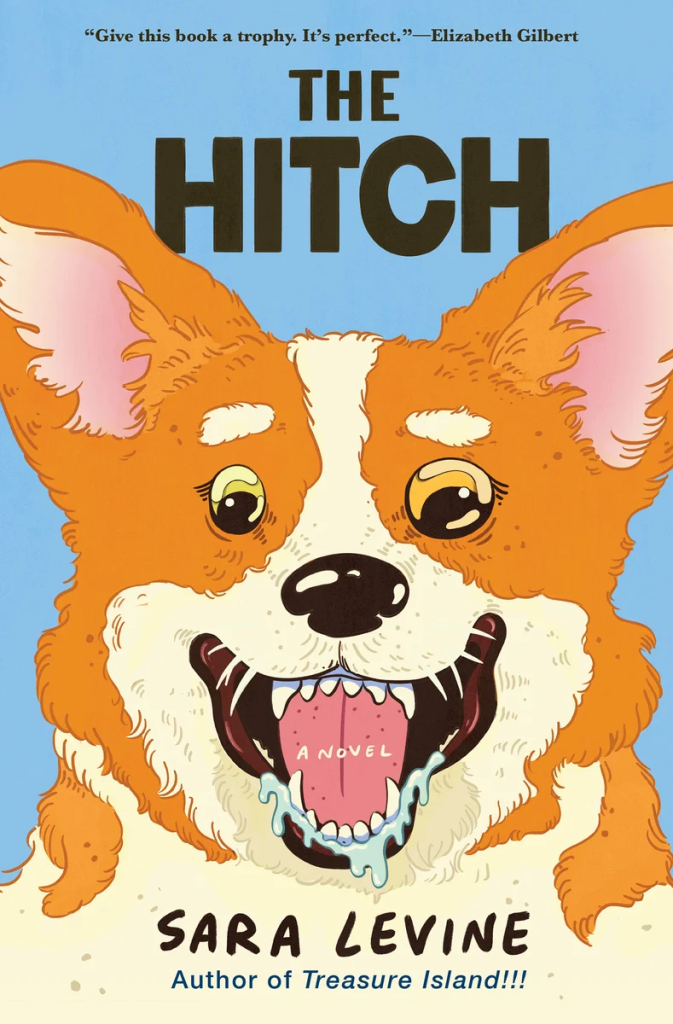

In my novel The Hitch, a woman looks after her six-year-old nephew for a week. She’s a secular, atheist Jew with an allergy to anything numinous. So when her nephew announces he’s been possessed by the soul of a recently deceased corgi, her world implodes. Compressed into a single, frantic week, the book accelerates the shift in her worldview from the material to the spiritual. But my main goal was to upset all the premises by which she organized her rational world. That’s what interests me—the shattering of the container in which the protagonist lives.

In the books below, the inciting incidents are familiar enough: a friend’s death, a husband’s betrayal, a move away from home. But the protagonists react in extremes. They lose their grip and things accelerate at an alarming pace. In life, one often moves slowly and clumsily towards a change of mind. These novels celebrate reckless speed, dizzying intensity, audacious rudeness, and the abandonment of social norms. They invite you to consider: What if I lost control?

Hangsaman by Shirley Jackson

First published in 1951, Hangsaman is the second, wonderfully strange novel by the American writer Shirley Jackson. Hangsaman begins with a teenage girl living at home with her hilariously awful family. “Natalie Waite, who was seventeen years old but who felt that she had been truly conscious only since she was about fifteen, lived in an odd corner of a world of sound and sight past the daily voices of her father and mother and their incomprehensible actions.” Her father is a pretentious domineering blowhard; her mother is unhappy and weak. Maybe when Natalie goes off to college, she’ll feel a bit better. Maybe she’ll like a professor, make a friend, join a club, give up conversing with an imaginary detective. Instead, Natalie leaves home and descends into new depths of alienation and self-torment. Her psychic collapse leaves little doubt as to how Jackson felt about the gender politics of higher education. And I thought I had a scary freshman year!

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated by Charlotte Barslund

Er mor død (translated from Norwegian to English by Charlotte Barslund) tells the story of Johanna, a recently widowed artist, long estranged from her parents and sister, who returns to Oslo for a retrospective exhibit. One night, a little bit drunk, she calls her elderly mother on the phone, but her mother hangs up as soon as she hears her daughter’s voice. Johanna becomes obsessed by the rejection and spins out, wracked by anxiety, longing, fury, mistrust, and shame. One minute she’s trying to remember what her mother said to her before Johanna left Norway, the next she’s stealing her mother’s garbage and stalking the woman as she visits her husband’s grave. Is Mother Dead is the book I recommend people read for Mother’s Day, when the rest of the world grows saccharine about mother-daughter bonds. Part thriller, part meditation, it is strong, sickening, and original.

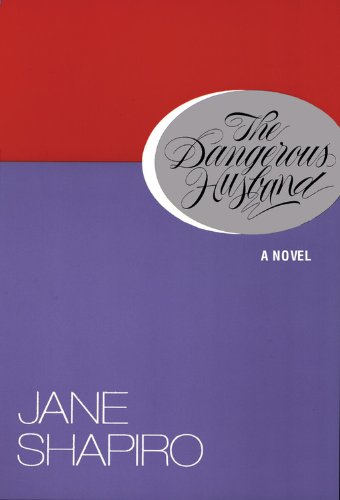

The Dangerous Husband by Jane Shapiro

The narrator of this perfect and criminally underrated novel has no name. The man she meets at a Manhattan dinner party is called Dennis. Being forty, they fall in love promptly, marry hastily, spend an appropriate amount of time eating expensive cheese and gazing at each other with “that lover’s mix of tenderness, gratitude, suppressed anxiety, and lust.” Then she realizes he has flaws. Dennis is weirdly clumsy. Accident-prone. Frankly, a menace. As the disasters pile up (broken bones as well as objects), marriage loses its allure. “It was turning out that my husband’s dishevelment was incomparable, potent, ramifying. It could destroy whole little worlds.” Unless she destroys him first. Determined to save herself, the newlywed hires a hit man to kill her husband. The Dangerous Husband shapes a fairy tale marriage into a screwball comedy with horror vibes, in luminous, pitch-perfect prose.

She-Devil in the Mirror by Horacio Castellanos Moya, translated by Katherine Silver

In Katherine Silver’s translation of La diabla en el espejo, Laura Riveria is rich, shallow, gossipy, and totally stunned when her friend Olga Maria is gunned down in her home. “How could such a tragedy have happened, my dear? I just spent the whole morning with Olga Maria at her boutique at the Villa Españolas Mall, she had to check on a special order. I still can’t believe it; it’s like a nightmare.” This is not the voice of Sherlock Holmes, Hercule Poirot, or Jules Maigret, but Laura is determined to solve the mystery of her BFF’s murder (in between catching the latest episode of a telenovela). Chapters change location (The Wake, The Burial, The Balcony, The Clinic), but Laura is the only voice allowed to tell a story that clearly exceeds her grasp. A dazzling, dark, hilariously one-sided account of a woman playing detective in post-civil war San Salvador, unravelling her mind and possibly some truth.

The Days of Abandonment by Elena Ferrante, translated by Ann Goldstein

Olga, 38, lives with her family in Turin. One day her husband announces he is leaving. Thinking Mario is experiencing a temporary “absence of sense,” Olga plans to wait it out—until she realizes he’s taken a lover. “Organize your defenses, preserve your wholeness, don’t let yourself break like an ornament, you’re not a knickknack, no woman is a knickknack,” Olga tells herself, but feminist theory can’t keep her intact. The Days of Abandonment is a frenzied chronicle of a woman’s descent into hell, accompanied by two small children and a sick German Shepherd. The details resist summary, but here’s a taste: When Olga bumps into Mario on the street, she throws him against a plate-glass window. “Into what world did I sink, into what world did I re-emerge? To what life am I restored? And to what purpose?” she asks. Eventually Olga ascends. A gripping, unapologetic book, shameless in the best sense.

Revenge of the Scapegoat by Caren Beilin

One day Iris, a writing instructor, receives a package containing documents from her teenage years: a play she wrote and two letters from her father, blaming her for the family’s ruin. After complaining to her friend Ray, who is about to have top surgery, Iris swaps her mildewy house for Ray’s doddering Subaru and drives off to the countryside. Did I mention the trip is poorly planned? Iris suffers from an autoimmune disease, and the funniest parts of this funny American book are the dialogues between Iris’s aching feet, whom she has named Bouvard and Pécuchet (after two characters in an unfinished Flaubert novel). The Subaru dies, and Iris lands in a field where she is stepped on by a herd of cows, then winds up working as a cowherd for a sexy lady who probably murdered her own husband and now operates a museum that’s only open one month a year. Then the story really goes off the rails.

The Vegetarian by Han Kang, translated by Deborah Smith

The Vegetarian (ch’aesikchuŭija, translated into English by Deborah Smith) centers on a Korean housewife who abruptly stops eating meat. Told in three sections, the novel is full of surprises, partly because it’s told from three points of view, none of which belongs to the vegetarian herself. Yeong-hye’s husband, a loveless man who views his wife as “completely unremarkable in every way,” begins the story of his recalcitrant wife, but his contribution can’t explain her motives, only document his growing fury that she resembles a “hospital patient” and no longer wears a bra or willingly provides sex. The second part documents her brother-in-law’s erotic obsession with her, even as Yeong-hye descends into psychosis and physically wastes away. The third part turns to her sister, In-hye, a hard-working, well-organized mother who is appalled, for her own reasons, at her sister’s transformation. We’ve all read books about women suffering under patriarchy, but has any protagonist ever responded to the violence by willing herself to become a tree?

Read the original article here