I feel like we look to fiction books to either uplift us and make us feel great about life and the world, or to devastate us and make us feel poopy about it. Personally, I believe that even in the latter instance that poopiness is meant to uplift us in how we go about living our lives afterwards. Has that book elicited a change in us at all? Are we behaving differently due to something in the novel, and acting out a hopeful outcome every day?

I feel sorrow stronger than I feel joy, so I love books that reflect that too, and make me commit to something through that feeling. The books that have affected me deeply have been almost always books with bad endings, where things don’t work out, and where things go from bad to worse, or where everything goes to shit at the end.

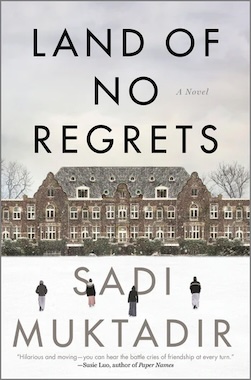

My own book, Land of No Regrets, is a book where things may go from bad to worse, but hopefully has something in it for readers to reflect on as a result. Four boys are sent away to a religious boarding school in rural Ontario, Canada, and quietly start rebelling against their new lives. They build up grand machinations for a different life, and dream bigger than their means, snowballing a series of events they have no control over to a cataclysmic result.

I bristle a little when people say they don’t have an appetite for heart-breaking novels, or books where things don’t work out. People can ultimately choose whatever they want to read obviously, but I really wish they couldn’t. I think people have a responsibility to entertain themselves and feel something when reading, and I think books that make them feel bad can do that just as well as books that make them feel good. I think these seven books do a great job of illustrating that. I would love for people to make themselves sad on purpose through books, and then reflect on how to be happier and better as a result. Small ask, I know.

Which books leave you feeling moved, books where everything works out in the end, or books where everything goes to hell?

Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Never Let Me Go is a novel set in a fictional boarding school, where we’re introduced to a sci-fi-y, speculative setting where some humans are bred to simply donate their organs and then die. In this pursuit, these donors are given these really nice lives where they’re healthy, eat well, get exercise, but also build strange social relationships as they slowly learn what their fates are to be. Stunted, awkward and depressed, they mostly lead short lives with loose connections with one another. We are introduced to hope through the rumours of donation exemptions granted to the doomed if they are in love and can prove it. Two characters, who are very much in love, hold onto this hope and start to build up little pieces of evidence of their love, like drawings or artwork they create. Slowly, readers start to learn about small pieces of evidence that support this theory, like older folks who are still alive and matriculated at these institutions, or stories about couples who were shown mercy. They might make it out right? And shut down the boarding school for good? Turns out, exemptions aren’t granted, it was all just that, rumours. Everyone you grow to love and hope for dies and we’re left to reflect on the human cost of development when an identity supersedes the value of a soul.

Noughts and Crosses by Malorie Blackman

Noughts and Crosses is a YA novel set in a world where white people were the slaves all along. Bear with me. It’s a speculative fiction series about racism, told through the eyes of star-crossed lovers who are not meant to be together, because one of them is white and one of them is black. The books are well written, like a modern day Romeo and Juliet, and are set with an interesting premise for teenagers who can still be surprised by thought experiments. At that age, you’re used to books having happy endings, and things working out for protagonists in the end. Sure, once in a while (Bridge to Terabithia, Where the Red Fern Grows, etc.) things don’t work out, but for the most part, you expect love to. This isn’t the case here. Racism grows, both sets of parents on either side are dead-set on separating the two, even trying to force the protagonist into an abortion. In the end, her fated lover is hung at the gallows for ‘raping’ her, and that’s how that book ends.

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai, by Donald Keene

No Longer Human by Osamu Dazai is an epistolary novel that feels foreboding from the first page to the last. The entire time I read it, I had the feeling that something was off and disturbing, and I loved it. Dazai doesn’t attempt to hide this feeling at all, telling readers exactly how his protagonist feels about himself, others, and the world around him. This dread permeates every page of the book as the self-pitying protagonist’s list of misdeeds grow. Guilt and shame abound as our protagonist Oda destroys marriages, becomes a drunk and a drug addict, finds sobriety and then relapses, completely unable to connect with humanity until finally, he’s taken away to exist in limbo amongst quiet nature. In real life, this is when Dazai killed himself.

Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

I read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in high school, as I’m sure many people did, and absolutely loved the real-to-life ending, and honest portrayal of pre-colonial Nigeria. As an idiot, I’m always learning, so I loved learning about the harsh-by-my-standards conduct of Okonkwo, a guy caught in standards of patriarchy that would make Andrew Tate pale in comparison. Okonkwo thought it was feminine to owe money to people. Anyways, living like this leads to disaster for him. The book takes place right around the time European missionaries showed up to colonize the land in the late 19th century, and demonstrates what happens when your community is made up of people who don’t think it’s cool to behead white messengers, and you’re also too ‘based’ to influence your community through love or diplomacy, or maybe things are out of your control. Either way, after a loss of face, dishonour, and exile, Okonkwo kills himself and becomes a paltry historical footnote.

Lord of the Flies by William Golding

Lord of the Flies’ impact on me can’t be understated. When I read it years ago, I loved how brutal and inhumane those children became over the course of events in the novel. I knew that when I wrote Land of No Regrets, I wanted to capture even the barest glimpse of the brutality humans were capable of, through the lens of childhood and young adulthood. That meant stranding them, not on an island, but at a boarding school, the setting for so many coming-of-age tales. In the same way Lord of the Flies is intended for adults, I wanted my own work to be intended for the same group, and to show the disastrous results of what happens when young people receive either no guidance or poor guidance as they indulged in every misdeed they could get away with. Fights, hunting pigs, theft, and finally, killing another kid, as chaos consumes the island.

The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

Books where things end in a painful, awkward, stunted manner are my favorite. They force us to wrestle and sit with a writer’s decision to tell us something we were not expecting. In The God of Small Things, Arundhati Roy weaves this masterful narrative of caste discrimination and class conflict, through the eyes of children. Rebellion can barely be afforded, and so one of the protagonists, a single mother, acts out through an affair with an Untouchable, the lowest caste of humanity in southern India. Communism is rising as the middle class family responds to it with alarm and opposition. One of the elder matriarchs of the family, Baby Kochamma, is an absolute piece of shit, a brown Auntie on hate roids, and manipulates events to bring about destruction and see everyone as miserable as her in life. I loved it. More than anything, Roy showed a true-to-life depiction of what happens every day, how people struggle and fail and die despite holding onto sad hope for a better life. I loved it.

A Fine Balance by Rohinton Mistry

Finally, A Fine Balance was the first book I read after finishing my undergrad, when the love of reading was almost beat out of me by having to read essays by Northrup Frye, and pretending Harold Bloom was an erudite worthy of worship. A Fine Balance left a greater impact on me because of the dire fate shared by all four protagonists. Indeed, it made sense that the book was so aptly named in reference to the middle sections that were a thin, fine respite that balanced the tragedy that would come before and after. In this same way, I wanted to present a story with some joyous balance in the middle as well. You really believe that this was going to be that diaspora literature full of hope, where young brown souls pull themselves out of ruin and poverty by their bootstraps, against the backdrop of Indira Gandhi’s India. An independent woman starting a business venture, sewer rats with dreams, and a young man studying hard. All you have to do is believe in the human spirit and extoll virtue. Instead, what really happened happens. Maim, castration, poverty, imprisonment, pity and suicide.

Read the original article here