There’s nothing more delicate than a line. In the world of my Triple Sonnets, my lines consist of approximately ten syllables each, mimicking our natural speaking pattern of saying ten syllables and then pausing. I love the tightness of this line—how plot, conceit, and yes, romance, are brought out in a compact yet deliberate space. Romance is a necessity, and because lines are delicate, getting to the point and excising unnecessary words brings us closer to the sincere truth.

When a loved one asks me, “What’s in your heart?” I feel closer to them. When seeking out poetry collections, I look for poems full of heart. When I say “heart,” I’m referring to the emotional core that moves the poem forward into volta—or the infinite turns of realization. In my day-to-day life, I often have trouble saying what I mean. I’m constantly telling myself: “Speak from the heart and others will follow suit.” I want to be less self-conscious. I want to be as fearless as I am in my poems.

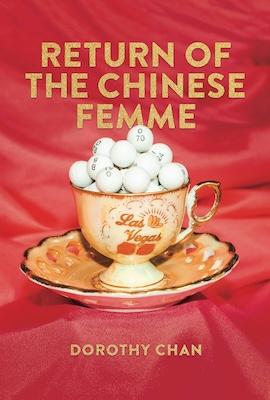

Return of the Chinese Femme, my fifth poetry collection, feels like a true return in many ways. Like its predecessors, Attack of the Fifty-Foot Centerfold and Revenge of the Asian Woman, it’s a return to the B-movie-and-Star-Wars-inspired-grand-gesture-filmic-title. More importantly, Return is a culmination of all the subjects I return to: food, sex, fantasy, pleasure, family, and of course, queer Asian femme identity within these themes. In Chinese culture, eight is the lucky number, because when it’s flipped upside down, it voltas into an infinity symbol.

I’m proud to present the following poetry collections by Asian American authors. These collections represent the infinite volta.

Feast by Ina Cariño

I love opening with a feast, and Ina Cariño’s Feast is a sensory-spellbinding-steamed-rice-in-the-throat collection of tongue and salt. An immediate intimacy, revealing history within the body, is established through food, or in Cariño’s words,

“my family dines luxurious—peasant food in crystal bowls:

seven thousand six hundred forty-one islands jostling in my soup.”

As the speaker’s tongue picks up salt, they further reveal:

“I salt the rice heavy when the meat is low, to trick my stomach

out of hunger. my muscles still remember old aches—as if suspended

in the salt of an ocean I crossed alone. how much can the body take?”

Salt is linked to the body, revealing intergenerational histories and traumas. This astounding collection reminds me how often, our bodies sense these histories and traumas before our minds even begin processing. I adore Cariño’s moments of unabashed clarity, like “I’m a different kind of brute from what the man on the train thought— ”. This queer declarative rings throughout, and I’m entranced by moments like “on days when I feel more like a woman / than a man” and “& on days when I don’t feel like a woman / or a man.” Cariño gives us intimacy from the queer body to intimacy within a familial history of cooking. “Perishable” is a standout in this collection, and I admire the familial intimacy of “my grandmother taught me how to slit / the milky belly of my favorite fish” to “…picked the meat clean / of tines—scooped it soft into my mouth.” Feast transforms the role of the mouth in Asian American poetics through intimate scenes.

False Offering by Rita Mookerjee

“I was born right after midnight on a date marked for chaos,” Mookerjee opens False Offering. This ultra-femme, ultra-kink, ultra-hot rage collection gives us the “hot trance” of “100 ways to make / your nipples show through your shirt.”

Mookerjee is a performer both on and off the page, and through Sailor Moon transformation sequences, we’re simultaneously graced with a queer appreciation of fashion and a limitless encyclopedic knowledge. She is creating her own 21st-century Vanitas painting with pleasures of long nails, velvet couches, cosmetics, and oils. Through these earthly pleasures, Mookerjee constantly urges the reader to fight the colonizer’s gaze. “Truly” is a standout, and through sexy usage of the forward slash, the speaker seduces us into the poem:

“How can you not be a lesbian when you watched movies with characters named truly scrumptious

I mean she is on the beach in white frills like a three-layer cake.”

A wonderous moment occurs with this intense, declarative volta, adding a further homage to American family cinema:

“I’ll start over

you can learn a lot about my sexuality if you watch chitty chitty bang bang.”

Tender Machines by J. Mae Barizo

Barizo’s stunningly fluid collection juxtaposes various modes of performance within a millennial backdrop:

“…the more Time presses the more

beautiful they become— lover / husband mistress child—I played

Goldberg Variations as she slept thinking of the geologic proportions

of Manhattan: limestone, marble, malachite.”

The quirk of language from the role (“lover / husband mistress child”) to the tactile (“limestone, marble, malachite”) plays off the sequential movements of Barizo’s hybrid work. “I’m alive I’m alive” is the meditative chant that closes “Woman on the Verge,” a poem that is representative of Barizo’s unwinding of what exactly makes a woman. The social constructions of gender are a major study throughout, and I adore her juxtapositions of “Mozart piano concertos” and “used the massage / chair as vibrator.” After all, what is highbrow? What is lowbrow? Sexual health and awareness is everything. Gender is a construct. Amidst the intersectionality of these topics, Barizo always crucially lands on tenderness—

“It is just past eight thirty

in the city and I wanted

to write a poem about

currency but it turned out

to be about love, what I mean

is to live is to rapacious:”

With finesse, she tackles the age-old question: “Is every poem bound to be a love poem?”. “Coda,” another stunner answers this:

“And what is it you hate? She asked.

Bureaucracy. And what is it you love?

he asked. Rivers.”

Organs of Little Importance by Adrienne Chung

Adrienne Chung is a true master of language. Winner of the 2022 National Poetry Series, selected by Solmaz Sharif, Organs of Little Importance combines Jungian psychology, Y2K nostalgia, critical theory, poetic footnotes, and sexy-quirks-of-peculiar-playfulness within high femme interiority and emotion. This collection is luxe and introspective. I am thoroughly transfixed with Chung’s language:

“When I understood that she did not

understand me at all, I left and pornographically cried in the

terra-cotta-tiled bathroom, the door to which did not open

onto a moonlit balcony where a handsome man stood smoking

a cigarette, with sex appeal and feeling.”

Chung defines zeitgeist: within the speaker’s personal experiences, she projects outwards into millennial culture and feminist theory and praxis. Within the playfulness of word combinations like “love languages,” “how he likes his martini, his hand job…,” and the glorious “dickmatized,” the speaker is critiquing the patriarchal structures of our society and putting up the metaphorical middle finger at the male gaze. Her speaker emphasizes ironies that further call out patriarchy; for instance, in “Blindness Pattern,” she states: “4. Color blindness afflicts men at a rate several times that / of women” and “5. (How unsurprising it is, then, that they have such difficulty distinguishing between stop and go?).”

Bianca by Eugenia Leigh

I would follow Eugenia Leigh’s speakers to the ends of this earth. Leigh is a master of balancing the delicate line with fierceness, truth, and reveal. “All my life I thought I was hard to love,” she writes, and it serves as the perfect landing and infinite volta into an exploration of healing. I admire how she names “Palpable rage” and “Our people, collectively unwilling // to let go, believe we share / a turbulence, a complex emotional cluster.” It is through these “complex emotional clusters” that Leigh’s speaker pivots us through familial trauma and rage at patriarchal forces that make her question, “How to be mother enough.”

I marvel at this pivotal volta in “Consider the Sun”:

“…Have you found what you’re looking for,

a handwritten No below it — and beyond the doorswobbled a lone dresser drawer holding a flask

and a book from 1928 called Come Be My Love.”

I will keep “Have you found what you’re looking for” in my poetic pocket.

Buffalo Girl by Jessica Q. Stark

I’m a femme born in the Year of the Snake sending a love letter to Stark, a femme born in the Year of the Tiger. This is a gorgeous collection framed by hybridity: stunning collages featuring the author’s mother grace us. Stark writes in “Ballad of the Red Wisteria”:

“Is red love with a knack

for breaking code first memories:

sure, first memories of home

include a pick-pocket

or two, a stolen newspaper

route coupon drawers and

ketchup packets: but that’s survival, baby”

Stark voltas several rounds here, from her skillful use of caesuras to the multiplication of red, to the emphasis on immigrant survival and honoring our Asian mothers and their sacrifices for us. She weaves through the tale of Little Red Riding Hood, drawing out the implications of this story through the Asian femme lens. In “Hungry Poem in the Language of the Wolf,” Stark continues her caesura collaging, opening:

“Call us what you will

thief, slut, mastermind, reaper, ordinary time

calls us mis-memory, we were born

in a time of great need,

wanted nothing that wouldn’t pay us

when my mother is

sick when I am sick, we spend it talking talking.”

And it is through our mothers that we learn defiance, hence the “knack / for breaking code.” In the title poem, Stark’s speaker narrates:

“history books are forever

missing the details of unfathomable

loss— providing discounts

on over-stocked goods You are my

mother —minor warrior— who has…”

from unincorporated territory [åmot] by Craig Santos Perez

Craig Santos Perez writes in from unincorporated territory [åmot], winner of the 2023 National Book Award for Poetry and the fifth collection from Perez’s unincorporated territory series:

“teach them

about our visual literaciesour ability to read

the intertextual

sacredness

of all things,”

I am awestruck by this collection with its sequential layering, intertextuality, abundance, and elements of surprise through language, honoring the author’s native Guåhan (Guam) and the Chamoru people and language. Perez utilizes the space of the lyric to show both the speaker’s present moment and Guam’s history. For instance, in “ginen the micronesian kingfisher,” the speaker pays homage to the extinct Guam Kingfishers, known as sihek. In this sequence, he opens with a literal sacred space for “avian silence” in the middle of the page. This is followed by an upside-down citation (at the bottom of the page) explaining the arrival of invasive brown tree snakes in 1944, thus putting the sihek population in danger. He closes with a sacred plea:

“will guam

ever be safe

enough

to re-wild

native

birdsong.”

Perez’s connections between food and empire made me the most curious.

“kikko is an ancient chamoru chief

who once caught 10,000 green sea turtles

& stored their tears in bottles”

In explaining the meaning behind the Kikkoman soy sauce name, the speaker then transitions into an even larger history within taste:

“yet where the greater east asia

co-prosperity sphere failed….

to the fifth taste of umami

& the sixth taste of empire.”

Excerpt from Feast © 2023 by Ina Cariño. Appears with permission of Alice James Books. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Bianca © 2023 by Eugenia Leigh. Appears with permission of Four Way Books. All rights reserved.

Tender Machines is published by Tupelo Press. Copyright © 2023 J. Mae Barizo. Excerpts reproduced by permission of Tupelo Press. www.tupelopress.org

Excerpt from Organs of Little Importance © 2023 by Adrienne Chung. Appears with permission of Penguin Publishing House. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from False Offering © 2023 by Rita Mookerjee. Appears with permission of Jackleg Press. All rights reserved.

Excerpt from Buffalo Girl © 2023 by Jessica Q. Stark. Appears with permission of BOA Editions. All rights reserved.

Excerpt published from from unincorporated territory [åmot] © 2023 by Craig Santos Perez. The poem appears with the permission of Omnidawn Publishing. All rights reserved.

Read the original article here