Poets for generations have contended with the indeterminable, fluid relationship between the speaker and the self. We all know the dictum to write what you know, but I find more possibility and permission in Eudora Welty’s way: “Write about what you don’t know about what you know.”

In my debut collection of poems, Theophanies, I explored matrilineage, motherhood, and gendered violence through the lens of the most personal thing about me that others know—my name. It would be easy, then, to read the poems and assume it is a wholly autobiographical account, that is pure confession. In poem after poem, you read Sarah, Sarah, Sarah, worn down from repetition like a bead on a rosary. But Sarah is a vessel that holds what I dream into it, a threshold I step across, hoping the way through leads to revelation or an encounter with the divine. Names are what I know—but knowing the names of Sarah, Hajar, Mary, and Eve didn’t lead me any closer to knowing the actual women they were, or the lives they led. So, I wrote into what I didn’t—couldn’t—know about them, through persona, portraiture, and forms both invented and received.

Tracing the contours of their names and personalities revealed to me my own biases, fears, and desires. It revealed to me that what I dismiss as personal is in fact deeply political, and that what I feel most intimately is in fact a portal to larger considerations of society and the political landscape, and my place and role within them. Each of these collections explores naming, the divided self, and feelings of alienation across time, geography, and shifting experiences with the speaker’s individuality. As Audre Lorde has said: “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” These are not single-issue books, but layered and rich and transformative. They cannot be reduced. Here, you’ll find illuminating work that uses lived experience as a springboard for deeper contemplation of home, selfhood, legacy, and belonging.

Portal by Tracy Fuad

“I lived for so long in a void,” Tracy Fuad writes in her sophomore collection, then later, “I thought myself wholly devoid,” bringing to mind the manifold properties of lack: is an empty space inherently so, recently emptied, or temporarily vacant, unfilled, but yet to be? But the title Portal offers the architecture of a threshold, a doorway into or out of, or an opening. In these precise, measured poems, Fuad brushes up against the (imagined, imposed) limitations of a life that is lived, and observed, and exhausted—and a conduit for more life still. I was moved and confounded by the atmospheric ten “Planetary Boundary” poems, which when read aloud rang in my ear like an alarm for each of the near-ten months of pregnancy. The self is at once a container and a hole, both precipice and witness: “I walked the city, a wet eye / Everything sticking to me / Or going right through.” Fuad’s preoccupations—semantics, origins, childbirth, our species depredations—are familiar, but handled with astonishing intimacy and candor. Evocative and probing, Portal is a collection I will return to for its music and wisdom: “When the self finally appears, don’t turn the self away.”

Ward Toward by Cindy Juyoung Ok

“[W]ho or what is the me in my?” Word to word, ward to ward—the poems in Ok’s debut Ward Toward collapse the walls of time and space, conscious of the page as a constraint but unwilling to be constrained by it. Selected by Rae Armantrout for the Yale Series of Younger Poets, this collection tunnels through idea and image to reach the noun and texture of experiences such as institutionalization and exile, and cautions, “no idea is like // prison …know dying is not like death and not even life / is lifelike.” Agile and discursive, Ok’s language bounds and abounds through wordplay, memory, and invented forms, and states, “I’m not native to any / place.” From apartments and wards to beds and checkpoints, Ward Toward is an architecture of scrutiny, a study of nation, selfhood, and performance—“The city’s in my name and its only borders / are my body’s, my counted and settled and made state.”

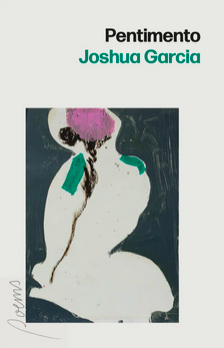

Pentimento by Joshua Garcia

Layered and expansive, Pentimento by Joshua Garcia leaves no stone unturned in its push-and-pull between art and form, the sacred and profane, image and text, sight and sound. These are muscular poems, grounded in the specific, and an intertextual, ekphrastic exploration of desire and devotion: “I want to know the names / of those who make reservoirs / of their own bodies.” Garcia works to disentangle pain from pleasure, and faith from self-flaying. Through persona, epistles, and self-portraits, the lonely speakers in Pentimento collect definitions, verses, names, and possibilities from the world around them, bolstered by a choir of figures ranging from roommates and friends to a therapist and Biblical figures. Garcia sets out in search of the sublime queer body, and in the process, excavates it powerfully from his own being: “i am still learning how void begets beauty / i am still / learning how to answer when called.”

The Palace of Forty Pillars by Armen Davoudian

Lyrically and formally deft, this debut collection by Armen Davoudian beautifully charts a queer and exilic coming of age. As much a narrative about adolescence and the mutability of national identity as the construction of narrative itself, The Palace of Forty Pillars reflects and refracts to harmonize two halves of a divided self. An Armenian raised in Iran, Davoudian recalls his childhood with musical clarity: “When I left home I thought I was the raven / sounding the future for echoes of my voice… // “…daily I renewed my prodigal choice.” Personal history is fractured and multiplied, halved and doubled—the elegant titular poem is a twenty-part crown of sonnets, which cleverly makes The Palace a collection of twenty poems or forty, depending on how you read it. This poised collection implements meter and rhyme to remarkable effect, paying homage to both Persian and English poetic traditions, and remakes all—personal history, war, family, lyric—in its own, singular image: “All is dual: // …All is dissolved: // …All is halved, // …the boy no more than a way of seeing.”

Self-Mythology by Saba Keramati

Selected by Patricia Smith as a finalist for the Miller Williams Prize, Saba Keramati’s debut enacts its title in lyric, cento, and self-portraiture. For Keramati, the hyphen—self-mythology, Chinese-Iranian—is at once a balance beam and a blade: “Two things can be true at once… / Hand pressed against glass hand.” Haunting and transfixing, these poems reckon with the inherited body and inhabited mind, collecting fragments to assemble a self. In “Self-Portrait with Crescent Moon and Plum Blossoms,” she writes, “I shape myself with the emblems I gather. / Let me write myself here…” Keramati takes confessional poetics to new heights, scrutinizing the self as a site excavated, and the home(lands) as a body whose scattered limbs might yet be reassembled. A number of lines are seared into my brain, triumphant and forthright in their brilliance—“Still / I am not so bold to think I am beyond my imagination.”

The Lengest Neoi by Stephanie Choi

Winner of the Iowa Poetry Prize, Choi’s debut collection The Lengest Neoi unfurls in poems that probe like a tongue into the void a pulled tooth leaves behind. Adding the superlative -est to the Cantonese Leng Neoi turns “pretty girl” into “prettiest,” establishing from the beginning the poet’s commitment to expansion in both vision and craft. Choi’s voice is matter-of-fact and penetrating, and deploys the intimately personal—names, family history, voicemails, emails—as a springboard for explorations of belonging, beauty, and connection. Formally inventive and delightfully sequential, language in Choi’s hand is stretched and patterned with wit and dexterity.

Particularly captivating are a series of sound translations after Jonathan Stalling, and “American | Ghost | Chestnut,” a crown of sonnets interrupted by a crossword. The final word of this collection is “instead,” apt for a book that explores alternate lives and versions of both the self and the home, for a speaker who writes, “My other name I’ve tried to adorn since I was born.”

Something about Living by Lena Khalaf Tuffaha

Winner of the 2022 Akron Prize for Poetry, Tuffaha’s third collection Something about Living clarifies Palestinian personhood by exhuming language for closer inspection. In a stunning thorn crown of sonnets, the speaker diagnoses the seemingly perpetual postures of empire and indicts the long arm of displacement, how “a parent’s exile can be upcycled.” In the face of ongoing atrocity, Tuffaha probes the limitations of articulation and presence to scrutinize what acts—of speech, defiance, or service—might be sufficient against the calcifying project of annihilation. In these poems, mercy is beckoned through an invocation of plurals, an empire sings itself to sleep, and a border is an arbitrary, inked line the poet writes upon and against. With precision and a keen eye, Tuffaha invites the reader across the threshold of the page to enact a living Palestine, to reorient the imagination against grief and loss, and toward “an architecture of return.” This a breathtaking collection that wields the personal as a looking glass into the collective, that centers Palestinian life as it is being lived, that privileges language that makes possible a choral, more sonorous living.

Read the original article here