Electric Literature Urgently Needs Your Help

For the 15,000 people who visit our site every day, reading Electric Literature costs nothing. And yet Electric Lit is not free. We need to raise $25,000 by December 31, 2024 to keep Electric Literature going into next year. If the continued existence of Electric Literature means something to you, please make a contribution today.

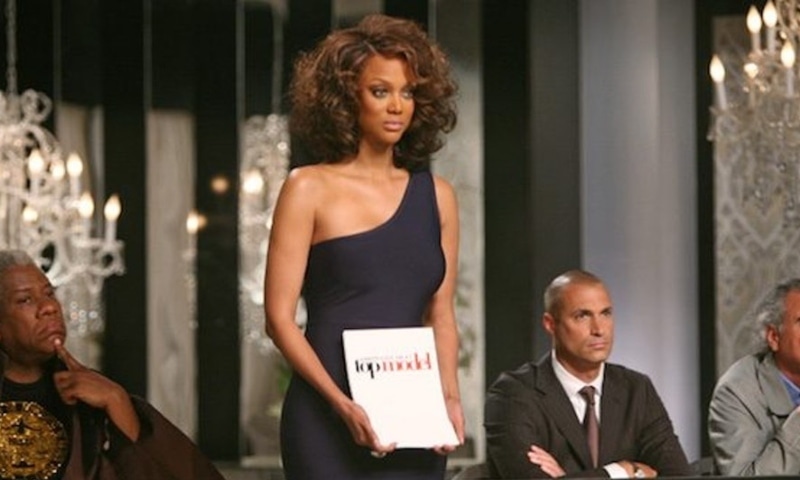

Girls who dream of becoming models are often looked down upon as shallow, desperate, and insipid—victims of a society that teaches women that their greatest value is youth and beauty. While the fashion industry is undeniably ripe for the exploitation of the young and vulnerable, models retain a mythic power in our cultural imagination. There’s a meaningful difference, under capitalism, between being beautiful and being professionally beautiful. Modeling isn’t just a job; it’s a beautiful job, implying a beautiful life, where work doesn’t look or feel like work.

At sixteen, I got closer to the dream than some (the semi-finals of a mall model search), but not close enough to dispel it’s power. Even as it became clear that I’d never make money off parading around in interesting clothes, the idea of doing so—of all the different versions of myself I could be—appealed in a similar way to writing fiction. More than being beautiful, I would argue that models are powerful because they are chameleonic, blurring the lines between embodiment and imagination, self and performance, flesh and fantasy. As such, they make for fascinating characters.

In West Girls, suburban teen Luna Lewis takes the performance of identity to extremes, styling herself as a mixed-race model ‘Luna Lu’. As well as being an answer to a lifelong ‘what-if’ (what if I had what it took, what if the dream became reality), Luna belongs to a tradition of literary women who turn to modeling in pursuit of a beautiful life and find more (and less) than they bargained for. The following list of books about models, ranging from young adult fiction to critical thinking, exposes the contradictory ugliness and transcendence of being professionally beautiful.

Hot Or What by Margaret Clark

A fixture of Australian school libraries, Margaret Clark’s Lisa Trelaw quartet follows the trials and tribulations of former ‘beached whale’ Lisa, who is scouted while working in her family’s hot dog van. The second book in the series, Hot Or What takes place in the cesspit of mid-nineties Sydney, where Lisa (rebranded as ‘Rebel’) is living in a model apartment. This retro Young Adult classic doesn’t shy from the grot of midnight 7/11 binges and purges, yet it’s also a bit camp (Lisa’s patron is named ‘Moira Sloane’) and packed with observational humour about Sydney’s upper echelons. Plus, the throwback slang is a delight.

Veronica by Mary Gaitskill

Nobody does ugly feminine longing quite like Mary Gaitskill and Veronica, published in 2005, is Gaitskill at her finest. Moving backwards and forwards in time, it centres on Alison, a diseased model-turned-cleaner languishing in northern California, and her inexplicable connection with the late Veronica. Daggy, uptight, and in love with a gay man who has infected her with AIDs, Veronica is an object of contempt, fascination, and, ultimately, deep fidelity for Alison. As well as its heartrending portrayal of an unlikely friendship, Veronica is masterful exploration of the amoral, subterranean allure of physical beauty. As Alison observes, ‘Here is Beauty in a white dress. Here is the pumping music, grinding her into meat and dirt.’

The Most Beautiful Job in the World by Giulia Mensitieri

If there was ever an industry calling for an anthropological investigation, it’s fashion. Originally published in French, this 2019 study by Italian academic Giulia Mensitieri exposes the labour conditions of fashion’s disposable slaves to genius: (non-super) models, interns, assistants, hair-and-makeup artists. While the surface details of these workers’ exploitation are exotic (models paid in Miu Miu rather than money, moonlighting as mannequins for Saudi billionaires’ wives), the underlying circumstances will be eerily familiar to any precariat ‘passion labourer’—writers included.

Meat Market by Juno Dawson

I never demand likeability of fictional characters, yet it’s hard not to love Jana Novak, the heroine of Juno Dawson’s Meat Market, a 2019 novel. A gangly South London girl from an immigrant family, Jana gets into modeling for some extra dosh. Grounded and intelligent, she is nevertheless believably vulnerable to the industry’s dizzying heights, exploitative lows, and crushing boredom. Tackling big themes—from #MeToo to class to casual sex– for a YA audience without being preachy is no small feat, but Dawson does so with absolute facility.

Tar Baby by Toni Morrison

Black, statuesque, and Sorbonne-educated, Jadine Childs is a high fashion model with a white patron, a white millionaire boyfriend, and a sealskin coat. Son is a fugitive sailor. On a lavish Caribbean island estate, their paths cross, igniting a complicated romance. This relatively forgotten 1981 novel is lush, erotic, and delves into internalised racism, misogyny, the social stratification of beauty with Morrison’s signature poetic intelligence.

Look At Me by Jennifer Egan

Charlotte Swenson, a falling star of Manhattan’s fashion scene, gets into a near-fatal car crash outside her hometown in Illinois, becoming unrecognisable. While the premise of Jennifer Egan’s second novel could be the jumping-off point for deep-dive into the beauty and disfigurement, the concerns of Look At Me are much broader: small town life, family madness, industrialisation, American dreams and nightmares, the construction and commodification of identity. It’s an everything-and-the-kitchen-sink novel, and doesn’t always cohere, yet it’s packed with ideas and weirdly prescient about online self-curation.

Aesthetica by Allie Rowbottom

I expected Allie Rowbottom’s 2022 debut, which follows an ex-Instagram model’s reversal of the cosmetic enhancements she underwent in her youth, to be both body horrific and psychologically disturbing. I didn’t expect it to be so elegiac. Like Veronica, Aesthetica is laced with grief: over youthful missteps, abuses, failures to thrive and connect. I came for an ironic literary take on fillers and BBLs, yet it’s the image of teenaged Anna thumbing through her phone while her mother dies of cancer that has stayed with me most.

Read the original article here