If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I have only lived in two places that were difficult to inhabit, but both are still very vivid. The first was when I was six, and my family lived in a static caravan (or trailer in the US) for six months. I can’t claim that we were living there because of any kind of hardship, but I clearly remember the ice on the insides of the windows in the mornings, having to wash at the sink with freezing water, and a very particular smell of damp cardboard walls. The second place was a squat when I was an art student. Living there was my choice, although money was tight. This house was damp too: a 1950s bungalow with no central heating and single-pane windows. It sat in the middle of an overgrown garden, isolated, despite being near the center of town. One of my clearest memories from that time is one night when someone outside—an unidentified stranger—moved around the perimeter of the house tapping on each of the windows in the dark.

I am still drawn to places that don’t welcome humans, places where people have once lived and now have left. I am curious about the objects they leave behind, and the bare minimum a person needs in order to make a house a home. Or, sometimes, the maximum.

In my novel Unsettled Ground, the main characters Jeanie and Julius live in what might appear to be an idyllic home: an English thatched cottage. But the reality is very different to the vision. There are mice in the thatch and holes in the ceilings which let the rain in. When Jeanie and Julius’s electricity goes off, they have to use oil lamps and candles, and cook on an old range. They have no central heating and an outside toilet. And the next place they try to make home is a dilapidated caravan on a piece of wasteland. But they are resourceful people and make the best of what they’ve got.

What kind of place could you tolerate if you had to?

Here are seven novels I love with houses that most of us might consider uninhabitable:

I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith

Cassandra lives in a crumbling castle with her father, sister and stepmother. At some times of the day, especially in a dusky kind of afternoon light when it can’t be seen properly, the castle appears romantic and beautiful. But in her diary, Cassandra wittily records the reality of the place: the icy draughts, how her father has sold off most of the furniture, the smelly, muddy moat, and how she has to take a hot brick to bed to keep warm at night.

The House of Paper by Carlos María Domínguez, translated by Nick Caistor

A Cambridge academic is killed by a car while walking and reading Emily Dickinson. Her successor receives a cement-covered book intended for his late colleague. Intrigued, he travels to Uruguay and eventually to a remote and desolate beach. There he finds a ruined house made of books. Whose crazy idea was that, anyway?

“What remained of the walls were bowed, jagged fragments, and in among the clumps of cement, tiny seashells, and dark lichens, I could make out pages of books baked in the sun then soaked, glued together like cuttlefish beaks, the type bleached and illegible.”

Burning Bright by Ron Rash

In this book of a dozen short stories, there’s just one with a house I wouldn’t want to live in, but a year after reading it, the place is still in my head. In “Back of Beyond,” Parson, a pawnbroker, goes out to his brother’s place because he knows that his nephew, Danny, has been selling stolen items to fund his meths habit. But it’s not until Parson gets there that he discovers his brother and sister-in-law huddling in a freezing trailer and Danny living in the family home:

“The room had been stripped of anything that could be sold, the only furnishing left a couch pulled up by the fireplace. Even wallpaper had been torn off a wall. The odour of meth infiltrated everything, coated the walls and floor.”

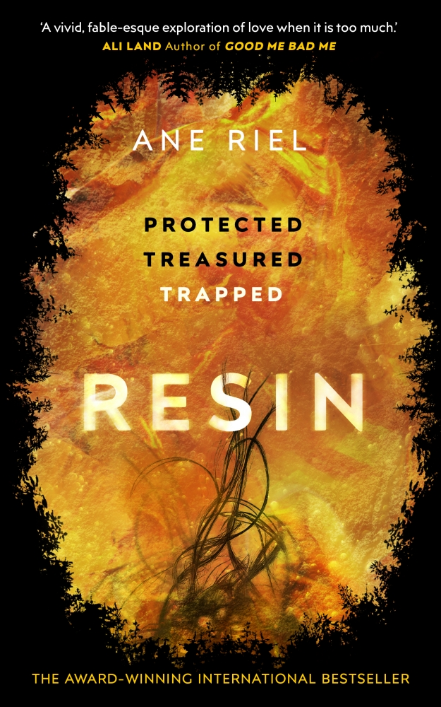

Resin by Ane Riel, translated by Charlotte Barslund

Jens Horder is literally a hoarder—his house and outside yard are filled with stuff, so that it is almost impossible to move safely between the piles. Jens reports to the authorities that his six-year-old daughter, Liv is missing presumed dead, even while he knows she is hiding in a container in his yard. Liv sometimes goes inside the house to visit her bed-bound mother who has also become part of the junk and mess:

“Shiny blue-green flies buzzed around open cans. Faded butterflies bashed their brown wings against the windowpanes somewhere behind all the stuff…. Small mice and much bigger mice with very long tails. Something was always scratching, grunting or squeaking somewhere. At times it would be Mum.”

Severance by Ling Ma

After a virus wipes out much of the world’s population, Candace—alone in New York but feeling she should still go to work—moves into her company’s office on the 31st floor of a skyscraper. She takes food from the employee’s vending machine and smashes her way into her boss’s office to sleep on his Mies van der Rohe sofa. It almost sounds idyllic: she sees a horse trot down Broadway and the stars in the night sky for the first time… if it weren’t of course for the plague and being all alone.

Medicine Walk by Richard Wagamese

16-year-old Franklin doesn’t really know his father Eldon, but when he is called to visit the dying man, and ultimately help him make a final journey to the backcountry, he goes. Eldon is living in the most evocatively described flophouse:

“Clothes had been flung and were scattered every which way along with empty fast-food boxes and old newspapers… the hot plate was crusted with grease and dribbles, and a coffee can overflowed with butts and ashes and a few jelly jars stuffed full of the same.”

A place not even Eldon wants to die in.

Stig of the Dump by Clive King

One day at the end of his grandmother’s garden, Barney falls into a disused chalk pit where he meets Stig, a caveman. Stig, well ahead of his time (this children’s novel was first published in 1963) reuses old junk to make his “cave” house: “There were stones and bones, fossils and bottles, skins and tins, stacks of sticks and hanks of string.” Stig of the Dump is one of my earliest memories of owning a book, and I still have a copy.