It’s impossible to create a cohesive linear narrative out of chronic illness. There often isn’t an identifiable starting point, and there is even less often an identifiable stopping point. There are, instead, waves that rise and fall with each episode, each flare, each day spent trying to keep one’s head above water while pain tries to drown you.

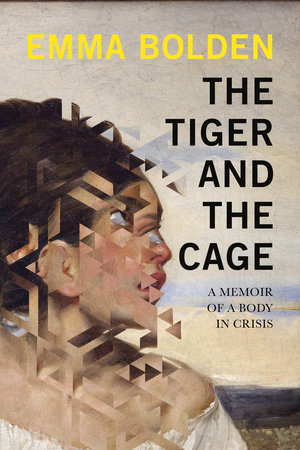

This is the challenge I faced when writing my memoir, The Tiger and the Cage: A Memoir of a Body in Crisis. How do I craft a narrative around a story that has no ending? How do I describe this indescribable, strange, impossibly individual, internal experience? The only way I could find was to move to the exterior: to see what happened to the life lived by the body, my body, when it was in pain. There is no place, no small inch of your life that illness does not touch. It decimates friendships, destroys your idea of who you are and want to be; it sets every dream you have on fire and doesn’t even leave ashes behind. It takes and it takes. But it gives, too.

Chronic illness changes the way that you focus. The smallest things—a perfectly-shaped ice cube, the red-lit numbers on an alarm clock—become the most important. You cling to the shreds of your life with all you have. You learn new ways to love the people who stay with you, who hand you glasses of water and aspirins and cold washcloths, who text you Doge memes and terrible jokes about Hobbits, who are present even when it seems like absence is the only thing you have left. A life lived in illness is evidence of everything at its most terrible and strange and beautiful and yes, even its most hilarious, as anyone who’s had a catheter around a house cat knows. It’s a life that can still be joyful—and maybe even more often, because dear God, how deeply you learn to acknowledge and appreciate those joys.

I’m not saying that dealing with chronic illness is a good thing. That would be crazy. What I am saying is that sometimes the only way to keep yourself from going crazy is to reshape the way you think about illness: This is when I learned to appreciate my parents. This is when I learned that ice on the back of your neck can keep you from barfing. This is when I learned to love Saltines. I am not always good at this. Sometimes it’s hard for me to think of anything else but pain. It’s then that I turn to other people’s words, if not for comfort, then perspective. The books themselves, these beautiful structures built out of words, stand as a monument to someone’s survival, a testament that says I have survived, and right now, you’re surviving, too.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin

There’s a certain level of guilt, for me at least, that exists in relationships when you’re a person with a chronic illness. I rarely talk about it, but it is not rare for me to feel like any kind of relationship with me is a burden on the other person. This book offers one of the best depictions of the myriad complexities of love and friendship from both sides. After a car wreck in childhood leaves him with severe life-long injuries, Sam throws himself into video games and, later, work as a distraction from what’s happening to his body—a tactic with which I am very familiar. The book follows the way that Sam’s obsession with work as well as his self-isolation (and sometimes self-sabotage) often does more harm than good, especially when it comes to his relationships with his friends and collaborators, Marx and Sadie. But this is also a book about healing, both in terms of Sam’s mind and body and in terms of his friendships, and it left me with a kind of hope I haven’t felt in years.

The Brand New Catastrophe by Mike Scalise

When Mike Scalise was 24, he went to the emergency room for a severe headache—that wasn’t a headache at all. It was, instead, an as-yet-undiagnosed tumor in his pituitary gland: a tumor that had just burst. Scalise’s book will bring you to tears and to laughter, and from the first word to the last, it’s an unflinchingly honest depiction of what it’s like to deal with a sudden medical emergency and with the chronic hormonal condition (acromegaly) Scalise must learn to navigate in its wake. In his passages about Andre the Giant, who also lived with acromegaly, Scalise examines how celebrity and popular culture can shape a person’s perception of an illness—which, of course, shapes perception of the person with the illness, even when that person is your self.

Don’t Kill the Birthday Girl: Tales from an Allergic Life by Sandra Beasley

I think of this as a hybrid memoir because of the ways Beasley examines the larger cultural context around an illness: in her case, food allergies so severe that something as innocuous as a birthday cake could, in fact, kill her by inducing anaphylactic shock. On one hand, the context is external, as Beasley explores the history of allergies as well as the ways that science, culture, and even religion determine how allergies are viewed. On the other, the context is extremely personal, as Beasley shows how her allergies affect all the decisions in her life, from how she has to place an order at a restaurant to whether or not she should have children.

Don’t Let Me Be Lonely: An American Lyric by Claudia Rankine

This devastating and ultimately indescribably book examines the ways in which our culture fragments to the point of incapability of human life. It is partly a powerful critique on the isolating nature of American culture and the connection—or, rather, disconnection—between the individual and the whole, seen through the lens of clinical depression. It is also an exploration of the breakdown of the very concept of community and the push against connection and towards the building of barriers in American culture. But it is also a book that offers hope in the form of the clarity art can bring, sounding a clarion call for the reader to recognize, honor, and care for others.

The Two Kinds of Decay: A Memoir by Sarah Manguso

As a college student, Manguso faced a sudden health crisis that left her paralyzed. Eventually, she is diagnosed with Chronic Idiopathic Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy, a rare autoimmune disorder in which the immune system attacks the myelin sheaths around a person’s nerve cells. As her “plasma was filled with an antibody that destroyed peripheral nerve cells,” she must undergo painful four-hour-long procedures to clean her blood. Both the disease and the treatment decimate Manguso’s life and force her to put her education on hold. In brief but beautifully powerful essays, Manguso presents a frank recounting of what it’s like to live with illness, eschewing traditional structure as well as the metaphors we use to soften the way we talk about disease, redefining the very way illness is perceived even as her own illness forces her to redefine the parameters of her own life.

This Appearing House by Ally Malineko

As devastating as it is to deal with chronic pain and illness as an adult, as a child, it’s unimaginable. What I love about this book is that Jac, the narrator, finds a way to accept the unimaginable through her imagination. A haunted house appears on an empty lot at the dead end of a street just as Jac approaches the fifth anniversary of her cancer diagnosis—and begins experiencing symptoms she fears means her cancer has returned. Though written for a middle-grade audience, Ally Malineko’s writing is so moving and skillful that I found myself in tears at the end. Following Jac as she finds her way out of the haunted house helped me come to grips with my own fears and feelings about chronic illness and how it had affected my family and friends.

In the Field Between Us by Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison

This collaborative poetry collection is a testament to something we don’t often see in illness narratives: a friendship that thrives, not despite of but almost because of illness. Through epistolary poems written to each other, Molly McCully Brown and Susannah Nevison share with each other the ways they’ve learned to navigate chronic illness and pain, co-creating both a testament to their friendship and a map of survival that, as a reader, I felt very lucky to hold in my hands.

Pain Woman Takes Your Keys, and Other Essays from a Nervous System by Sonya Huber

Here’s the thing with chronic pain and illness: sometimes, there is no resolution because there is no cure. In these extraordinary essays, Sonya Huber explores this fact through form as well as content. The essays are often experimental, deviating from the traditional inverted checkmark shape of a narrative to borrow structures with which anyone who’s dealt with chronic pain is very familiar: numbered lists, symptom scales, daily records, and short bursts of scenes. Huber’s experimentation with form allows the experience of pain on the page in raw and honest ways, offering the reader a visceral portrait of what it’s like to deal with pain you know may never end.