The more I learn about memory, the less I trust my own. Neuroscientists tell us that the process of remembering does not mean that we are retrieving fixed images or scenes from a sealed vault in the brain, but rather that we are firing synapses along specific pathways, leading us back to a moment from our past that changes a little every time we send for it. The stories we tell ourselves about our past are crafted and filtered, mutable and unreliable. We cannot trust that what we believe to have happened actually happened unless we can locate evidence from outside ourselves to corroborate our own story. And even then—what if the evidence is faulty?

In the age of misinformation and artificial intelligence and the Internet, this inability to trust what we remember has grown and morphed. Now we’re often unable to trust what we see, what we hear, and even what we feel. Then again, perhaps it’s unfair to blame technology… After all, isn’t this the province of literature? Haven’t stories always made us see, hear, and feel things that are not there?

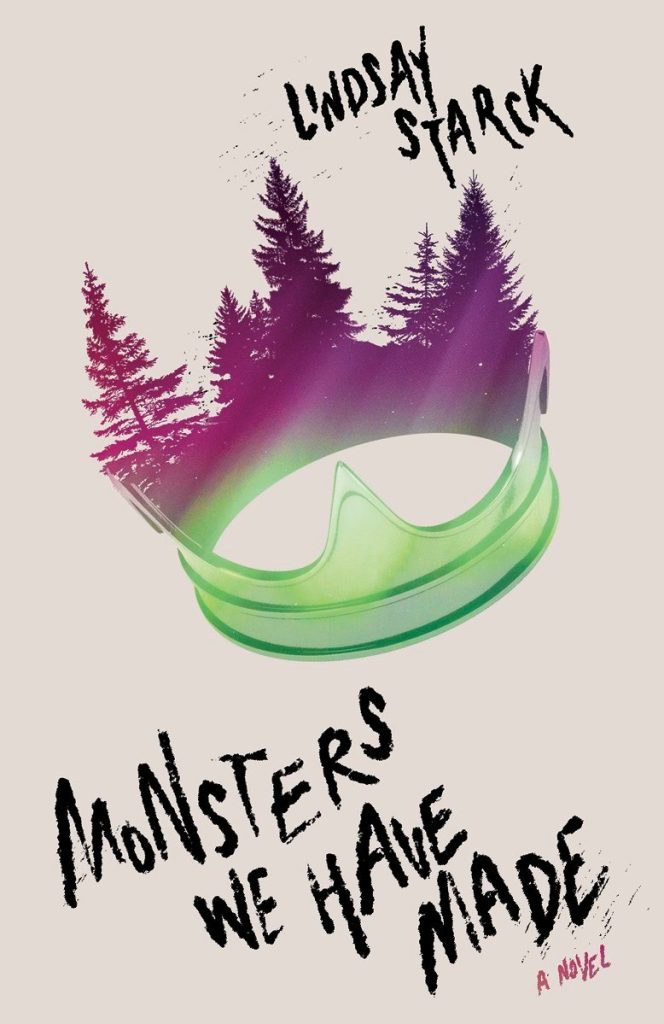

In my new novel, Monsters We Have Made, a dark and terrifying Internet legend inspires two young girls to commit a devastating crime. Thirteen years before the story opens, Sylvia’s nine-year-old daughter Faye attacked her babysitter in the name of the Kingman, a creature that she and her best friend discovered online. In the aftermath, Sylvia’s marriage, home, and family fell apart. Now Faye, recently released from a detention facility, has gone missing, and she’s left her four-year-old child behind.

As Sylvia hunts for the missing Faye, tracking her through unfamiliar cities and primeval forests, she is haunted by memories of the family she lost and by the monster who is growing ever more real to her. “In my peripheral vision,” she tells us, “I glimpsed quaking branches, cold white waves, stars colored brightly as jewels. Sometimes from my bedroom window: the crest of a black cloak coiling around the corner of the garage.” When she pages through old family photo albums, she sees the Kingman lurking just outside the frame; when she peers through the window, she sees a wooden face staring back at her.

“Sanity is a matter of borders: inside versus outside, truth versus dream, fact versus fiction,” Sylvia reflects. “How can a person tell, at any given hour, on any given sleepless night, what side of the line she is on?”

The books in this list are also concerned with those borders. What is real versus what is imagined? What is remembered and what is crafted? How do we know when to trust our perception, what do we do when our memories or our senses fail us, and what does “evidence” even mean in a world as slippery and shifting as we are?

Consent: A Memoir by Jill Ciment

“Scenes in a memoir,” Jill Ciment writes in her new book, “are no more accurate than reenactments on Forensic Files.” This claim is both startling and suitable for a new memoir (Consent) that revises a previous memoir (Half a Life) that Ciment wrote twenty-five years ago. The older narrator of Consent analyzes her younger self’s “memories” in Half a Life to illuminate how those memories were deliberately—sometimes creatively—crafted. In her first book, Ciment framed her relationship with an art teacher thirty years her senior as a choice she willingly made. In the second, she wonders whether it was ever possible for her seventeen-year-old self to willingly choose a married, middle-aged father of two. In a recent interview, Ciment described the first memoir as the product of the “shared mythology” that defines a relationship, and suggested that she didn’t tell the whole truth (even to herself) because she wanted the story of her marriage to be one in which she was empowered, not victimized. Her observation that “a memoir is closer to historical fiction than it is to biography” reminds us that our own memories, too, are crafted: polished, cut, exaggerated, shined.

Biography of X by Catherine Lacey

Simultaneously a fictional biography and a counterfactual history, Biography of X follows narrator C. M. Lucca as she struggles to uncover and record the mysterious life of her recently-deceased wife, X. The trouble with X is that she was a performance artist whose entire life, we learn, was a series of performances—making it difficult for the grief-stricken Lucca to figure out which elements of their relationship were real. Lucca chooses to write X’s biography (expressly against X’s wishes) because she needs to be reassured “that our life had actually happened, that I had been there with her, and that I hadn’t imagined all those years, her company, our life, the home we had in each other—though I was forgetting her every day, forgetting whatever was between us and whom she’d been to me and who I’d been beside her.” With X gone, Lucca becomes the sole keeper of those memories; which means that she can no longer be certain of their veracity.

A Tale for the Time Being by Ruth Ozeki

Ruth Ozeki’s A Tale for the Time Being, a novel concerned with the slippage between past and present, is filtered through protagonist Ruth, a writer unable to complete a memoir about her mother’s struggle with Alzheimer’s. When she finds the diary of a Japanese teenager, Nao, Ruth decides to track her down. As Ruth suffers increasingly from lapses in memory and dreams that bleed into reality, she becomes desperate for “corroboration from the outside world… that Nao and her diary were real and therefore traceable.” Over time, her own sense of self becomes uncertain: “Was she the dream? Was Nao the one writing her into being?… She’d never had any cause to doubt her senses. Her empirical sense of herself as a fully embodied being who persisted in a real world of her remembering seemed trustworthy enough, but now in the dark, at four in the morning, she wasn’t so sure.” Ruth’s uncertainty begs the question for readers, too: what evidence do we need in order to trust that what we have experienced is true?

Piranesi by Susanna Clarke

I really love this strange, ethereal, fantastical, gem-like novel, which takes place in a magnificent, classical, sprawling mansion full of waves and statues. The protagonist, known to us as Piranesi, lives in “the House” alone and engages twice a week with a mysterious, irritable person we know only as “the Other.” When the book opens, Piranesi is content in his strange existence, unaware that anything might have come before it. But then he discovers that pages have been “violently removed” from his diary, and that other entries look like his handwriting even though he doesn’t remember writing them. When the Other informs Piranesi that he does, indeed, forget things, Piranesi’s initial shock gives way to disbelief. “‘The World’ (so far as I can tell) does not bear out the Other’s claim that there are gaps in my memory,” he muses. “And so I have to ask Myself: whose memory is at fault? Mine or his? Might he in fact be remembering conversations that never happened? Two memories. Two bright minds which remember past events differently. It is an awkward situation. There exists no third person to say which of us is correct.” Even without that third person, Piranesi’s new wariness of his own perception and experience leads him to conclude that the Other “is right about one thing. I am not as rational as I thought.”

Lost Children Archive by Valeria Luiselli

At the heart of Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive are a boy and a girl traveling with their parents toward the Mexican border in Arizona. Their parents are sound documentarians working on different projects: their mother on the children’s immigration crisis at the border (a story that has been ignored) and their father on the last Apache leaders on the American continent (a story that has been erased). “The story I need to tell,” reflects the mother, “is the one of the children who are missing, those whose voices can no longer be heard because they are, possibly forever, lost. Perhaps, like my husband, I’m also chasing ghosts and echoes. Except mine are in history books, and not in cemeteries.” In the backseat of the car, the boy and girl play at being lost children, too; and when they finally take off alone, their game becomes real. The novel deals with the erasure of historical memory, the creation of familial memory, and the lengths we go to in order to prove to ourselves and each other that something happened. “When you get older,” the boy informs the girl, “and tell other people our story, they’ll tell you it’s not true, they’ll say it’s impossible, they won’t believe you. Don’t worry about them. Our story is true, and deep in your wild heart and in the whirls of your crazy curls, you will know it.”

In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O’Brien

One of my favorite novels to teach, Tim O’Brien’s In the Lake of the Woods is a vivid, sylvan thriller whose experiments with form and style contribute to its mystery. Centered on the disappearance of Kathy Wade—the wife of a Vietnam veteran-turned-politician John Wade—the book intersperses conventional narrative chapters with sections labeled “Evidence” (which consist of citations and interview fragments) and sections labeled “Hypothesis” (which describe all of the fates that could have befallen Kathy Wade). As the story progresses, John Wade struggles to remember what happened on the night she disappeared—but he has spent so many years deliberately forgetting what he saw and did in Vietnam that his memory is dangerous and unreliable. Although the “missing person” in the novel is ostensibly Kathy, John’s failure to remember what he did or didn’t do to her shatters any sense of a coherent self and transforms him into a type of missing person, too.

Minor Detail by Adania Shibli, translated by Elisabeth Jacquette

Adania Shibli’s slim and devastating Minor Detail is less about the erasure of the self and more about the disorienting experience of moving through a once-familiar, beloved landscape that is in the process of being erased. The first half of the novella depicts, in spare prose and unflinching detail, the rape and murder of a Bedouin woman by Israeli soldiers in Palestine in 1949. In the second half, an unnamed narrator in Ramalla undertakes a dangerous journey across borders and through checkpoints in order to learn more about the crime. The evidence she seeks is the kind of minor detail “like dust on the desk or fly shit on a painting, as the only way to arrive at the truth and definitive proof of its existence.” But no one she meets can tell her anything about the crime; and the further she travels into an occupied land from which all traces of Palestinian villages have been erased, the more disoriented she becomes. In a space in which the unimaginable—rape, murder, the bombing of the office building next door to hers—is so unrelenting as to become mundane, one’s very existence begins to feel surreal, unlikely, and nightmarish.

The Girl I Am, Was, and Never Will Be by Shannon Gibney

“The literature of adoption,” writes Shannon Gibney, “is a fictional genre in itself.” In The Girl I Am, Was, and Never Will Be, Gibney leans into this argument by weaving together her own actual adoption story (including documents and photographs) and the story of what might have happened if she had remained with her birth mother. By intentionally combining memoir with speculative fiction, the book illuminates the multiple pathways that exist between the past and the present. Gibney’s fictionalization of memory liberates the narrator from the impossible project of perfectly reconstructing the past, provides her a new angle on the present, and reminds us that the boundaries between inside and outside, truth and dream, fact and fiction are much more permeable than they appear.

Read the original article here