Moms are weird. Scary, even. You were inside her. She’s still inside you: seeds of dysfunction planted by even the most well-intentioned, over years of clumsy tending. She was a mere mortal, suddenly transformed into a minor god, blessed with raw human material and challenged to shape it into something as close to perfection as possible.

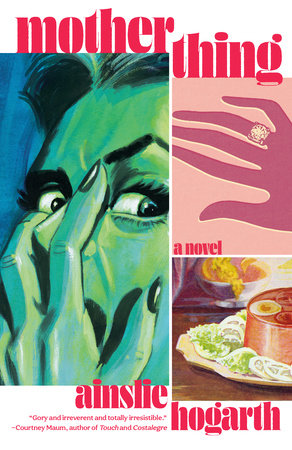

The extent to which mothers and children are capable of destroying one another is so profound that we, as a species, will probably be writing about it right up until the moment the planet extinguishes us. My new novel Motherthing is just such a story—a dark comedy about a woman named Abby, who’s been lucky enough to marry the greatest man in the world, Ralph. She’s working hard to process her relationship with her monstrous mother, both so that she can be a better mother herself one day, and be an excellent partner to Ralph in the meantime. Her plan is thwarted, of course, when she’s thrust into battle with the vengeful ghost of her mother-in-law, Laura, back from the dead to prove once and for all that no one is good enough for her son.

Motherthing is a love story, a comedy, and a horror story, which could probably be said of most mother-daughter relationships as well. We love our moms, sure. Our moms are hilarious, aren’t they? But also our moms can be dark as hell. Like Motherthing, many of the following books don’t fit easily into any one genre, but all of them deal with the unique horrors of creating and sustaining life.

The Good House by Tananarive Due

Two years after the shocking suicide of her teenage son, Angela Toussaint returns to the place where it happened—The Good House: an ancient estate in Sacajawea, Washington, passed down by her grandmother, a Creole herbalist who the townsfolk ignorantly regarded as a supernatural doctor. But the tragedy has altered things in The Good House, and in the town as well. Strange disappearances, acts of inexplicable violence, mysterious deaths. The Good House is a genuinely frightening horror novel for true horror lovers about indescribable grief, inherited trauma, and power the past has over us.

Chouette by Claire Oshetsky

Chouette opens with a very funny woman named Tiny realizing that she’s pregnant with an owl baby. Part twisted, feminist fairy tale (à la Angela Carter), part surreal horror (evoked immediately by the book’s epigraph, a quote from David Lynch’s Eraserhead), and sprinkled with just the right amount of heart and humor. In this book, the pregnant woman is a kind of chimera—a creature made up of two distinct beasts. Tiny has special powers, special abilities, but, just like her owl baby, she doesn’t quite fit in. This book makes it heartbreakingly clear that being different isn’t inherently difficult, but rather is made difficult by the failures of society.

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell

Fever Dream is a marvel, the lovechild of Samuel Beckett and Amelia Gray, and best devoured in one sitting. It takes place in a rural hospital clinic where a woman named Amanda lays dying; a boy named David sits beside her. David pushes Amanda to recall the trauma that put her in the hospital, and in the process opens a vault of maternal dread, body horror, and profound loss. Visceral, thrilling, sad—I may never stop thinking about Fever Dream.

The School for Good Mothers by Jessamine Chan

The School for Good Mothers is a nightmarish glimpse into a not-so-distant future in which mothers who’ve failed to meet a certain standard are taken from their children and sent to an abusive rehabilitation center. Chilling, harrowing, and all the more horrifying for its plausibility, this book is about an everywoman fighting to get her child back, and also raises important questions about the limits (or lack thereof) of government control, and the intense pressure society places on mothers.

Future Home of the Living God by Louise Erdrich

In the apocalyptic world of Future Home of the Living God, women are suddenly giving birth to earlier, regressed forms of humans. The species is de-evolving, slowly but surely, and pregnant women are at the forefront of its demise. Except for Cedar Hawk Songmaker, an Indigenous woman adopted by well-meaning white parents, whose unborn child might be one of the few “normal” babies left. Structured as letters written by a first-time mother to her unborn child, this book is equal parts funny and grim, making it one of the most heartbreaking pieces of dystopian fiction I’ve ever read.

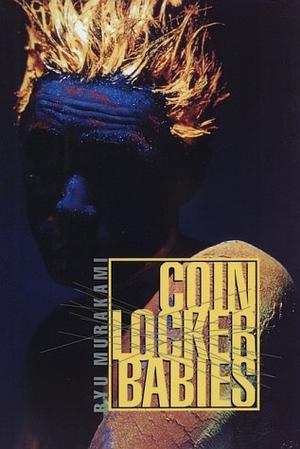

Coin Locker Babies by Ryū Murakami, translated by Stephen Snyder

In 1980s Japan, an alarming number of babies were left abandoned in coin-operated lockers. Ryu Murakami’s novel is a deranged, genre-bending bildungsroman, about two coin locker babies, saved from the lockers and raised together on a remote island. Though they grow up to lead very different lives, they’re both possessed by finding out the identity of their real mothers, the women who abandoned them to such an awful fate. And, eventually, in gruesome, horrifying twists, they find them.

The Need by Helen Phillips

Molly, an exhausted working mother of two, clutches her infant and her toddler in the corner of her dark bedroom while an intruder may or may not be lurking just beyond the door. The Need starts, and stays, as gripping as its first chapter. As Molly, a paleobotanist working on a mysterious site called The Pit, grapples with parenting’s ceaseless cyclone of labour and guilt and exhaustion and joy, Phillips introduces a menacing stranger who threatens to take it all away. The Need is vivid, creepy, and incredibly engaging.

The Hole by Hye-young Pyun, translated by Sora Kim-Russell

When Oghi wakes from a coma, he discovers that he caused a car accident, which took his wife’s life and left him paralyzed and badly disfigured. His caretaker is his mother-in-law, a lonely widow who is devastated by the loss of her only child. She neglects Oghi, leaves him isolated in his room, and spends all of her time digging up the garden that her daughter worked so hard to cultivate. The Hole is a tense, subtle study of loss, isolation, grief, and the disturbing reality that even those closest to you can be strangers.