As a young child, I’d wake in my bed, certain I was somewhere I didn’t belong, crying desperately to go home. And so, my relationship with the uncanny began.

In Sigmund Freud’s 1919 essay “The Uncanny,” the basic definition of the term is, in-of-itself, a contradiction. For the uncanny, Freud uses the word unheimlich, from his native German, which translates to not of the home. This definition suggest that uncanny events must involve the unknown or unfamiliar, but as the essay continues Freud explains that the uncanny can also be an experience where something heimlich, of the home, becomes unheimlich when private or concealed information is revealed. In the uncanny, the familiar and the strange overlap.

As an adult, I’ve come to understand that many of the uncanny experiences of my childhood were the result of a secret revealed when I was too young to understand it. My father was a small-time weed dealer, tending to his crop and clients after his children were put to bed. The strange voices in the hallway, the ring of a spoon against the rim of a coffee cup chiming through the dark, the footsteps in the attic that bowed the ceiling above my bed: these experiences were all real. The isolating uncertainty I felt as a child seeking answers, only to be dismissed, contributed to the uncanny nature of these events. The revelations that shift an object, space, experience, or person from familiar to strange can be based on something concealed by others, or, something a person has concealed from themselves. In my case, the majority of my early uncanny experiences were a combination of the two.

But there remains a handful of events that I cannot explain, and these uncanny experiences have deeply shaped my interests as a writer. At work on my most recent book Hatch, a collection of interlinked prose poems about an artificial womb and an apocalyptic future, I was haunted by an image from my childhood. In a clearing, in the pine woods, far back from any road, there was an abandoned farmhouse. It was almost entirely intact, and on a bench in one of the bedrooms, someone had laid out a green dress and a pair of low-heeled leather shoes. Someone had laid these objects out like they were about to put them on, and then…

For years, I wondered what had happened to the family who left the farmhouse behind. What had become of the woman who meant to wear the green dress? Though I’ve never written their story, the farmhouse, the green dress, the low-heeled leather shoes, the unknown woman and her unknown fate, all feel a part of everything I write. Stories have always been the closest I can come to understanding what I cannot.

Just as I’m invested in the complexities of the uncanny in my own writing, I find it thrilling to encounter in the work of other authors. The nature of the uncanny is highly subjective, informed by what haunts each of us most. Below are eight uncanny books that hold space in my heart and quicken its beat, even as they chill it.

Such Small Hands by Andrés Barba, translated by Lisa Dillman

“We were once a happy city; we were once happy girls.” But with the arrival of Marina, the survivor of a car crash that killed her parents, life at the orphanage is changed. The girls, who narrate Barba’s darkly dreamy novella as a collective we, have only their shared experiences of the world, including a set of rules they have invented and agreed upon. Marina’s arrival serves as a violet disruption of the we. To the orphans, who were previously absent an awareness of their own fragility, Marina’s scarred body introduces mortality and the possibility of serious injury and death. She becomes an unsettling object of fascination and repulsion. Like a virus, Marina sickens the body of the collective. A ritualistic nightly game, where each girl takes a turn as an object for the others’ pleasure, only quickens the spread. An I among the we, Marina leaves the orphans with a sinister, forked choice: assimilation or purgation.

Disquiet by Julia Leigh

The return of the exile, disrupting the status quo established in their absence, is a familiar plot, which Leigh injects with adrenaline by pairing one return with another, creating mirroring events that are striking both for their similarity and difference. In Disquiet, the day that Olivia, the daughter who ran away years before, returns to the family chateau, bruised, with a broken arm and two secret children, is also the day that her brother and his wife are returning from the hospital with their first child. Olivia’s arrival, with a young boy and girl trailing behind, is a shock. It’s doubled then darkened with the news that the expected grandchild is stillborn. As an act of compassion, the parents have been permitted to bring their infant home—a chance to say goodbye. The chateau’s grand entry is full of balloons to celebrate a homecoming, but uninvited company has crashed the party, and the birthday girl, baby Alice, was born dead. What follows is an eerie unraveling of family secrets and loyalties that decay decades of carefully maintained control.

White is for Witching by Helen Oyeyemi

Published 15 years ago, White is for Witching is a novel boiling with the ghosts of empire and war. Tragically, over a decade later, it has not lost any degree of its political or humanitarian urgency. By setting the book in Dover, whose famous white cliff coastline has been at threat of invasion since the 10th century, and is the location of a contemporary immigration removal center, Oyeyemi is able to shine a spotlight on British nationalism and xenophobia. Here, in Dover, during a slew of violent attacks against immigrants, a mentally and physically fragile girl, Miranda Silver, walks into the night never to return. But is that really what happened? White is for Witching is chronologically disruptive, beginning in the present and shifting between various times in the past. The novel starts with Miranda’s disappearance as described by three of the primary narrators: her protective and possessive twin brother Eliot, Ore, Marinda’s first romantic interest, the clear-eyed daughter of a Nigerian immigrant, adopted by white British parents, and finally the sinister, sentient Silver home at 29 Barton Road. Yes, the house is alive. 29 Barton Road is also viciously racist, enjoys supernatural powers of compulsion, and has a domineering sense of ownership over generations of Silver women. Where is Miranda Silver? Is Miranda alive? To answer these questions, you’ll have to read White is for Witching for yourself.

The Hole by Hiroko Oyamada, translated by David Boyd

With her husband’s job transfer, Asa leaves the city and her unsatisfying job behind for a new life in a small town. Conveniently, her in-laws own a house, neighboring theirs, that the couple can move into rent-free. What a windfall! Except, Asa has no memory of this house, despite previously visiting her in-laws. This is one of many holes in Oyamada’s uncanny novella. An unsettling slow burn, The Hole opens with Asa experiencing a series of vague discomforts best kept to herself lest she seem ungrateful. The move. The new home. The transition from underpaid temporary worker to housewife. The constant proximity of her helpful, professionally successful mother-in-law. The stagnancy of a long, hot summer. As Asa’s isolation increases so do the peculiarities around her. The song of the cicadas grows impossibly louder. Children’s laughter cuts through the hot air, but Asa cannot see any children. One day, she falls into a hole that seems perfectly designed to trap her. Freed by a passing neighbor, Asa discovers the land is full of holes. Like a deranged game of Whac-A-Mole, children’s heads rise and disappear. A strange, fanged creature, who dens in an empty well, appears. With the discovery of physical holes, Asa discovers more and more holes in her memory. A transformation, terrifying for its banality is underway.

The Law of the Skies by Grégoire Courtois, translated by Rhonda Mullins

The portrayal of children as vessels of innocence is shattered in The Law of the Skies. A dozen six-year-olds and three adult chaperons tumble off a bus into the woods for a short camping trip. None of them will survive. While the vast majority of violence inflicted by children is the product of ignorant exploration with no harm intended, there are those chilling few who take a true pleasure in causing damage. Enzo, the murderous boy hunting his classmates across Courtois’s nauseating novella is one of those. To make a little girl cry, Enzo smashes a snail. Later he will wield a rock against his teacher. An unrelentingly violent parable, The Law of the Skies sets good against evil in an unforgiving natural world. When Enzo dispatches adult authority, his classmates are left to fight or flee. Like Lord of the Flies, The Law of the Skies demands readers consider the conflict of appearance versus reality, the necessity of rules and order, and the innate nature of evil. Despite knowing from the first page that there are no survivors, the narrative propels forward with a hope that innocence will be rescued and order restored. In denying this longed for conclusion, The Law of the Skies is a destabilizing exploration of our relationship to violence.

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin, translated by Megan McDowell

“They’re like worms. … Like worms, all over,” a boy murmurs on the opening page of Samanta Schweblin’s Fever Dream. Writhing with tension, this slim novella is structured as an ongoing conversation between two characters. The first is Amanda, who lies blinded in a hospital bed with no understanding of how she came to be there. The second is David, an unsettling young boy guiding Amanda toward a critical memory she has temporarily lost. Schweblin’s quick-paced, dialogue-driven structure creates a sense of defamiliarization for the reader. Entering into Fever Dream everything is strange. Gradually, Amanda recalls that she is staying at a vacation home in the countryside with her daughter, Nina. Here, a neighbor, Carla, befriends Amanda and shares a bizarre story. Carla’s little boy, David, has no soul. Once, he was a perfectly normal child, but now Carla says he is a “monster.” Believing that her neighbor must be unstable, Amanda dismisses the story. Hints at its truth are woven into her experiences in the country, but Amanda fails to see them until the situation is dire. Earlier in Fever Dream, the phrase “rescue distance,” representing how far Amanda can be from Nina while still able to protect her, is introduced like a blaring klaxon. As much as it is an uncanny work, Fever Dream is about motherhood, and the desperate, even deranged lengths a parent will go to protect her child from the visible and hidden dangers of the world.

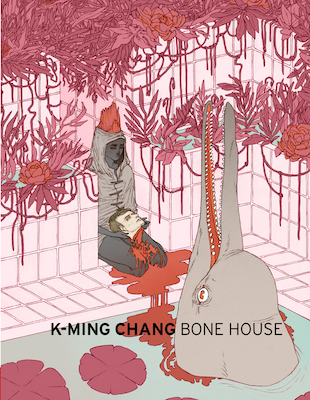

Bone House by K-Ming Chang

An object as fine and eerie as a dollhouse miniature, K-Ming Chang’s micro-chapbook Bone House is a queer, Taiwanese American retelling of Wuthering Heights. Chang is a writer who pairs the beautiful and the grotesque in a way where each compliments the other. Bone House is rich with imagery that is simultaneously alluring and repelling. A girl is hung by her long, thick hair. Bones arrange themselves to send messages from the dead. The boundaries between what is natural and what is supernatural are porous and Chang’s characters accept what they encounter with little questioning.

After moving into a butcher’s living, meat-hook studded mansion, the story’s unnamed narrator discovers the complex and destructive love story of Millet, a foundling, and Cathy, the lover who ultimately rejects her. As Cathy’s insistent ghost performs acrobatics above the narrator’s bed, demanding to be seen, they develop their own attraction to Millet. How does a person leave a toxic relationship when their lover returns as a ghost to haunt the house they once shared? This is Millet’s challenge: to free herself (and Cathy) from a cycle of desire and violence where love and consumption intertwined. Cleanse it with fire. Burn, baby, burn.

Burnt Sugar by Avni Doshi

“You should worry about your own madness instead of mine.” These are the words that Tara, a woman diagnosed with dementia, hurls at her adult daughter, Antara. As her mother’s health diminishes, Antara takes her in, ostensibly, to care for her. But, the two women share decades of resentment for one another. When Antara was a baby, Tara, a dissatisfied Indian housewife, all but abandoned her daughter to pursue a relationship with an exploitive guru. Later, Tara will bring a young and powerless Antara to the ashram where she is neglected and subjected to casual abuse from her mother and the guru’s ecstatic followers. In a reversal of roles, an adult Antara finds herself positioned to care for the mother who failed to care for her. What is a child’s obligation to such a parent? Where Burnt Sugar slides into the territory of the uncanny is in how Antara faces this question. Simply put, she wants revenge. Despite Antara’s insistence that she needs her mother out of her life, her actions indicate an obsession with the woman. As long-held secrets are revealed, Antara becomes mother to a little girl of her own. The tension in Burnt Sugar crackles as each of the women is forced to see the other in a new light.

Read the original article here