Nature as tangled forest, as oil-drenched bayou or salt desert. Nature as flux and change. In all the books discussed here, the writers use ideas of nature as backdrops for perplexing and life-changing character dilemmas. The ideas of nature are different in every case, and the protagonists are all searching for something they don’t quite understand the nature of, but the common thread is nature always presiding, abiding, inspiring and looming. Nature provoking. The searches happen within the context of an overriding concept that’s much bigger than the protagonists are, and crystallizes within a metaphorically resonant space that augments the complexity of both concept and character. In their various encounters with these spaces, whether it be an uncharted wilderness, apocalyptic landscape, or flickering apple orchard, the characters all shed one kind of skin and grow a different, sometimes extraordinarily richer one.

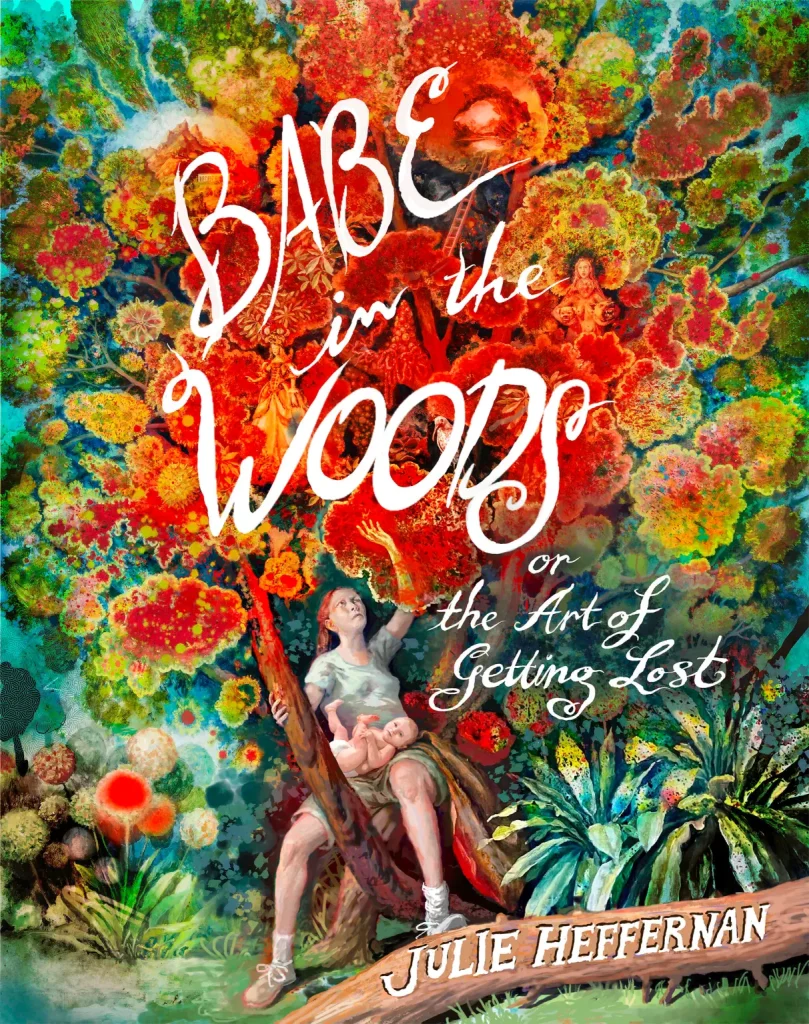

My book, Babe in the Woods, or the Art of Getting Lost, didn’t start out in the woods, or with any kind of space in mind. It didn’t even start out with much of a story. What it had was a Concept, which I thought was Grand. Concepts are serious stuff, I thought, laudable, possibly even game-changing, but in a narrative, I discovered, they’re ineffectual by themselves. While all the books I’ve selected here include at least one big concept–one that dwarfs the human stories swirling around it–it’s those puny humans and their wayward, unruly yarns that grabbed my heart. They’re the vehicles for bringing big concepts to life. But I didn’t understand that when I started my own project.

The first draft for what would eventually become Babe tried to make its big idea primary. I wanted to shed light on what makes art “art” and give readers visual lessons in how ideas in great paintings are actually structured, how their messages are made available to an audience and deliver wisdom. The problem was, this mission amounted to a Mother Tree story, way bigger than the scope of any individual life, so there was no way to grasp it.

A graphic novel is the perfect medium for analyzing such powerfully visual things as paintings, and what I wanted to do in my book, I thought, was show readers how the compositions of great paintings elucidate subject matter and deliver insights that make us better and wiser. That’s the sort of thing I teach—why great paintings matter—but that ambition isn’t a story. The story Babe needed turned out to be right in front of me, lying in wait, but it was one I’d never thought worth telling. It struck me as just an unruly weed because my thinking was too caught up in the Mother Tree mega-canopy idea. Mother Trees don’t need us in the slightest. We’re better off cultivating the new seedlings that do.

My own seed of a story wasn’t much more than an innocuous speck when it first occurred to me: a woman lost in the woods with a baby, that was it. But slowly it grew: she began to notice things, look more closely at the world around her, peer underneath things to discover ants and termites and her own urgent issues, ones she’d never given much thought to. She remembers things she’d squelched, discovers a need to reconcile with her dad and have that conversation with her mother she’d never dared have, all while moving through a terrain full of obstacles, real and otherwise. And, with that grand concept accompanying her, she discovers a space even grander.

Always unpredictable, nature becomes a trope for all we can’t control. In these nine novels the settings vary widely, but each of them challenges the reader to engage deeply in that very unpredictability. Just as weather catalyzes change in the environment, these characters encounter conditions that spark changes in themselves, and in the reader too.

The New Wilderness by Diane Cook

When I read The New Wilderness while in the middle of writing Babe, I felt immediately in kindred country. The story follows Bea and her sickly five-year-old, Agnes, who have volunteered for an experiment with 18 others to leave civilization—now polluted and overcrowded—and decamp to what’s called the Wilderness State—the last bastion of untouched nature— and the only chance Agnes has, possibly, to heal. It had been forbidden territory up until now, rapacious humans having proven themselves unworthy of it.

Cook addresses many issues, not the least of which is how to deal with the conundrum of bringing children into a world ravaged by centuries of exploitative behavior. There’s betrayal, danger, terror around every corner; but Agnes thrives. Now Bea has to wrestle with the idea of losing her daughter in a way she’d never considered. The question is not only how does one survive in an actual wilderness with no survival skills but also how might we address the even more difficult question: what kind of world do we want?

The Overstory by Richard Powers

Eight stories about nine people, The Overstory follows characters from different eras, backgrounds and histories whose lives, like roots, are intricately intertwined with each other through their profound engagement with trees. Some characters are fictional, some based on real people: I learned about Julia Butterfly Hill through the character of Olivia Vandergriff, and the novel’s tree scientist, Patricia Westerford, is based on the actual Canadian researcher Suzanne Simard, who studied how trees have their own unique intelligence, evinced in richly complex mechanisms of communication.

Each of Powers’s characters is beautifully drawn, with their own individual quirks and obsessions; each has their own corresponding tree. Powers’ gift is to festoon the reader in gorgeous language while also teaching us a wide and gorgeous variety of things, from the history of the Chestnut blight and ancient Chinese manuscripts to how to survive up in a tree for a year. But mostly he gives us lessons on trees, their amazing biology, how they talk to and protect each other, how they’re so much grander and more important than us. He wraps us up in imagery involving all the invisible linkages that occur between root systems, how they sustain each other and the larger environment in ways none of us can see, and the multistory book itself is structured like this root system. In the end you understand what it means to seek the wisdom of trees in thinking about our own fractured world.

North Woods by Daniel Mason

A single apple tree grows in the woods some time back in the 1600s, around which a dwelling is built, gets renovated, changes ownership, and eventually falls into ruin. But, before that, it shelters a host of different characters, living and dead, whose lives and stories span three centuries. From a young couple fleeing the strictures of their Puritan community to modern day Nora, who uses the house as a respite after she crashes her car nearby, these layered stories about endurance remind us that the past is vivid and always with us should we care to notice its traces in the smallest of details, like the age lines in a face.

We meet a variety of vividly drawn characters including a lusty beetle, a bevy of ghosts and the unforgettable Charles, who remakes his life in that same Northwoods dwelling, cultivating an entire apple orchard alongside that first tree. We meet his daughters, twins who return to the story after death, along with other inhabitants of the house who also can’t leave it. A conman, a lonely painter, a schizophrenic writer, all the characters are presented as part of a cycle of seasons divided into the twelve months of the year, and alive on the page in a world beset by the kinds of secrets that can ruin or, in the hands of wise writers, save us.

Drive your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk, translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones

Janina, an eccentric, middle-aged Polish woman contends with a spate of animal killings she discovers in the forest outside her village. As we follow her story, meeting villagers along the way with whom she constantly tussles, we gather that mere human psychology isn’t adequate to the question of how a world becomes deranged. That seems to be why Janina is attracted to astrology, using it to make sense of the madness going on around her. Only the stars can take on such mysteries, she suggests, the distance they have on humankind offering the wide perspective of eternity needed to explain our unfathomable human cruelty.

As the narrative unspools it looks as though the forest animals are fighting back, and we travel alongside Janina as she interacts contentiously with her community, quotes Blake, and gives people nicknames that describe their true character. Her unique voice allows us inside the tangled complexities of not only a cast of bad actors fomenting chaos around her but also her Wise Woman intelligence.

Parable of the Sower by Olivia Butler

Nature run amok is the backdrop for this dystopian novel about a teenage girl forced to decamp from her family home after a collapsing economy, war, disease, drugs and chronic water shortages have ravaged the entire United States. After Lauren Olamina’s family is killed when a fire destroys their home in what was supposed to be the one safe neighborhood left in LA, Lauren, who has the gift (or curse) of hyperempathy, is forced to face the deadly outside world on her own, armed only with the seeds she’s managed to bring with her in the hopes of finding a place safe for sowing them, and in that way, beginning again.

As she heads north, Lauren takes up with a diverse crew of other refugees fleeing conditions like prostitution and debt-slavery, and in the course of their travels she becomes a force for hope in their dismal lives as she slowly confides her idea for a new religion, one she calls Earthseed. Her god is Change—more of an idea than something to venerate—but still something to grasp and hold on to for people doomed to live in a world riven by short-term wins and losses, the danger and uncertainty of a rudderless existence. Her idea is a way to keep going, without illusions but nevertheless with hope.

In the Distance by Hernan Diaz

A young Swede in the 19th century goes on a kind of backwards pilgrimage in search of his brother whom he lost after they disembarked in NYC. Taking another wrong turn, he finds himself alone and penniless in California, going east during the westward expansion. Inordinately tall and knowing little English, Hakan is viewed as a murderous madman by some and as a legend by others. In the course of his travels, he survives a maelstrom of violence, invidious characters, and horrifying circumstances that bring him to the brink of death over and over again.

Terrifying characters abound, thwarting our ideas of type: hooker as sensual hag, murderous cult leader with a modicum of wisdom, naturalist going slowly insane in his search for the impossible. The desert Hakan traverses back and forth is a nightmarish place lightened only by his meeting a naturalist who is one of the only good characters in the book. This man studies imaginary creatures in alkaline pools and shows Hakan how to find water in the dry dust of a dauntingly unforgiving terrain. Despite his honesty, integrity and good intentions, Hakan over time develops a reputation as a notorious outlaw, unable to avoid doing violence in circumstances that bring even good men to the brink.

When We Cease to Understand the World by Benjamin Labatut

In this novel, Labatut takes us into the complex and troubled minds of some of our greatest physicists—Fritz Haber, Werner Heisenberg, Erwin Schrödinger, among others—struggling with the most profound moral and scientific questions underlying all of nature. We get a glimpse inside the mind of the man who brought us such miracles and horrors as nitrogen-based fertilizers (which allowed us to feed an exploding world population) and the pesticide Zyklon B (which was the gas the Nazis used to exterminate millions of Jews). We become intimate with the thoughts of the men who mastered the radical intricacies of nuclear physics and quantum theory, eventually bringing us the atomic bomb.

For someone who barely passed high school Physics, I found the opportunity to peer into the minds of such geniuses, through the clarity and precision of Labatut’s language, an extraordinary experience. These are minds engaged not only in pondering the greatest mysteries of the natural world, but also unravelling their knottiness. Thinking along with them for a few hours is breathtaking. Labatut’s ability to find words that function as metaphorical equivalents for baffling concepts in quantum physics, which manage to enfranchise even the STEM-challenged like myself, feels almost miraculous.

Strangers in their Own Land by Arlie Russell Hochschild

Awarded a Medal of Honor by Obama, Hochschild is a renowned sociologist who travelled deep into the Louisiana bayou to live and work with poor, mostly conservative members of a community employed by but also preyed on by the oil industry. Her mission is to tell the real story of those people and their lives, detailing all the maddening and mostly counterproductive excuses they give for retaining that industry. It has been systematically destroying their environment and denying them a reliable livelihood for generations, yet they work to ensure it isn’t thrown out of the state.

An elite Berkeley academic, Hochshild is caring and down-to-earth; for that reason she becomes a trusted member of a community who might otherwise have shunned her. This involvement allows her unique access to the people and their contradictory behavior. Oil giveth and oil taketh away and these people have had the very ground they’ve been walking on for eons taken away from them: the whole town is swallowed by a sinkhole created by oil drilling.

In her book, Hochschild has made an enormous contribution to the left’s understanding of what makes such people tick. She theorizes about economic disparity with the image of a ladder on which people stand, hoping to slowly move up, rung after rung, waiting patiently to go that step higher, but being constantly thwarted by strangers—immigrants, the poor and needy, gays, etc.—who jump in front of them. They are constantly led to believe that outsiders—not the system—are cheating them and their children of their just deserts.

Shaman by Kim Stanley Robinson

What was it like to hang out with Neanderthals 32,000 years ago in the prehistoric time when we inhabited the earth alongside them? What really was shamanism, before it became a contemporary conceit? Who were the actual people who painted the Chauvet caves, and how did they do it? Were they anything like us at all?

Only someone like Robinson with real science bona fides could take up such questions and turn them into historical fiction. We are first introduced to Loon, the main character, naked and alone in a stark world. We journey with him on his rite of passage, with no tools to help him in the his many struggles. His very nakedness is the medium that allows readers to assume his skin as he fights his way through the forest and encounters numerous calamities, including breaking his ankle. He seeks the means to bind it using only forest tools, figuring out how to manage while facing even more dangerous forces.

There are shamans, healers and lovers, all rendered in beautifully imagined strokes. The shaman passes down stories and wisdom that Loon must learn and eventually shape in his own way The healer is an old woman whose practice is born of observation, the first tool of science. The lover is an outsider who helps Loon’s people see the world in a new way.

Robinson’s remarkable ability to transport us to such a distant time and place—one that most of us couldn’t possibly imagine even though it’s somewhere in our genes—is the boon of this book. Robinson provides precisely drawn characters we can readily identify with even though they have very little language. A consummate researcher, Robinson invented their language using a combination of Basque and Proto-Indo-European, thinking carefully and compassionately about every word.

Read the original article here