If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

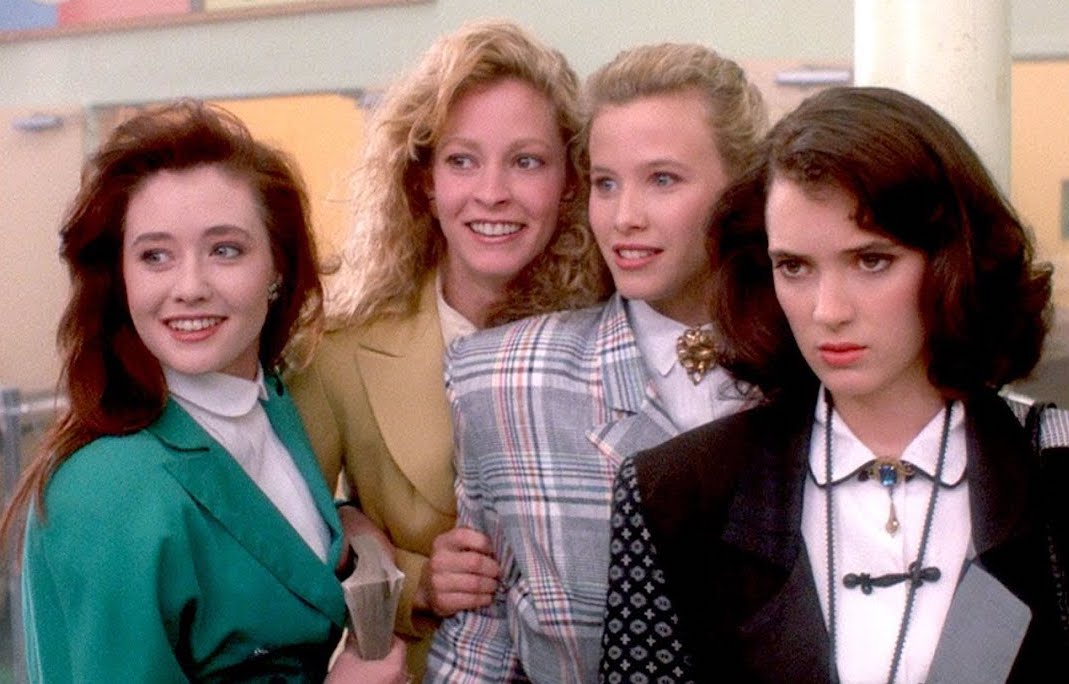

The first time I saw a picture of the girls in the Manson family, I was in college, I think, and was shocked to see that the girls looked like me: young, long-haired, smiling with other young, long-haired girls. In the most infamous pictures, the girls are gleeful as they walk into court, matching in prison-issued blue shift dresses and darker blue sweaters, tiny x’s carved into their foreheads. The incongruity between their age, their prettiness, and that little bit of self-desecration is jarring, the x a visible indicator of the unseen darkness inside. Every part of the Manson saga is unbelievable—from a cult of hippies living on a movie-set ranch to the slaughter of a pregnant movie star—but one of the aspects that has made the crime of enduring interest is the fact that the murders were committed by young women.

Generally, as a society, we aren’t comfortable with the darkness of women, and we certainly aren’t comfortable with the darkness of girls. We learn as children that girls are made of sugar and spice and everything nice, and it is the boys, made of snips and snails and puppy dog tails, that harbor an inclination toward darkness. Their ingredients are horrifying, but inherently more interesting. I can remember hearing that rhyme as a little girl and imagining that if you cut me open, inside there would essentially be the contents of a cupboard, ready to be mixed and baked, but inside a boy, there was mystery, violence. Boys possessed the elements needed to conjure magic: eye of newt, tail of dog. All I could make was a cake.

But the truth of course is that girls contain darkness and light, snips and spice, just like any other person in the world. And honestly, the experience of simply being a girl contains plenty of darkness in and of itself. Adolescence is a time of intense emotions, physical changes, aching desires, a growing awareness of what the world expects you to be and the realization that you might not be meeting those expectations. But we are asked to tamp down that wanting, to navigate the big feelings and strange transformations in a way that ensures we remain pleasant, polite, and pretty. If that isn’t dark, what is?

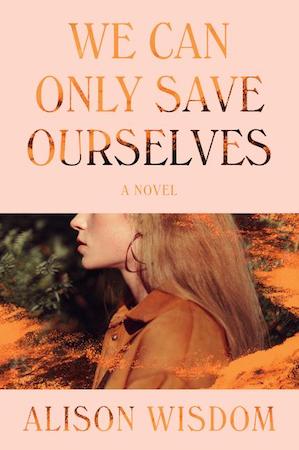

My novel We Can Only Save Ourselves is very much concerned with this dark side of girlhood. Loosely inspired by the Manson family, it follows Alice Lange, a “perfect” teenage girl beloved by all in her idyllic neighborhood, as she rejects the life laid out for her and instead follows an enigmatic stranger to his home, a bungalow full of other young women like Alice, all eager to lead more authentic lives. There is darkness there, in the house, among the girls, and, Alice learns, within herself. Meanwhile, the mothers of Alice’s old neighborhood must grapple with what her abandonment means for them and what it reveals about their golden lives—did the crack Alice’s departure left in their carefully constructed world allow darkness to seep in, or is it possible the darkness was there all along?

In honor of all the girls who do bad things, here are nine pieces of literature that explore the dark side of girlhood:

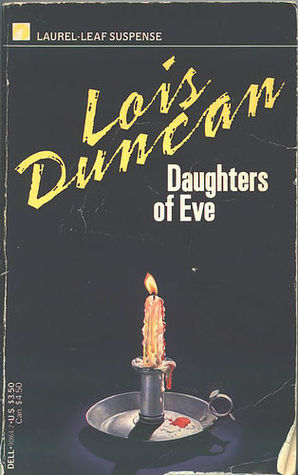

The Daughters of Eve by Lois Duncan

Growing up, I read every one of Duncan’s young adult novels, but the one that disturbed me the most wasn’t the one about the girl with the evil twin or the one with the creepy boarding school but The Daughters of Eve, a story with no supernatural elements or murderers—just a group of high school girls who form a club under the supervision of their teacher, Ms. Stark. She tells the girls they have lived their lives unknowingly oppressed by men—by their fathers, by the boys in their school—and she encourages them to rise up and gain independence. After examining their lives, the girls begin to enact small revenges against the boys and men they know until things dangerously, violently escalate. Like the girls, we too see the truth in what Ms. Stark teaches but find ourselves troubled by the means they take to seize control of their lives. A story of power and rage, The Daughters of Eve is both a call to action and a cautionary tale.

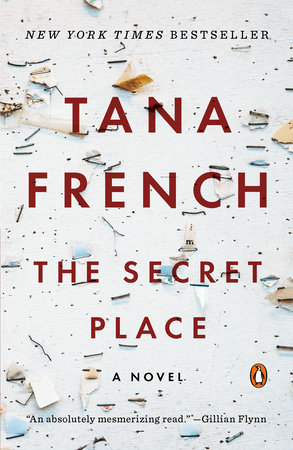

The Secret Place by Tana French

A year after a boy’s murder at St. Kilda’s, a prestigious boarding school, a note is found pinned to a bulletin board, announcing only I KNOW WHO KILLED HIM. Detectives Stephen Moran and Antoinette Conway spend a day at the school, interrogating the students and untangling the truth from the lies they hear, but when it becomes clear that two rival groups of girls are at the center of the web, Moran is confronted by the surprisingly sinister side not only of teenagers but also by the shadowy world of wealth and privilege. Moran is drawn to St. Kilda’s, its posh exclusivity and beauty—intoxicatingly different than his own upbringing—and is slow to see the darkness there. French draws a parallel between the hidden danger of the school and the danger lurking among the groups of girls—she toys with our expectations of their capabilities in the same way she allows Moran’s own preconceptions to be challenged.

Everything I Never Told You by Celeste Ng

In Ng’s debut novel, we do not get girls as killers or temptresses or devious liars; instead, Ng explores the pressure a teenage girl experiences, the darkness an external thing that slowly becomes internalized. The body of Lydia Lee, the girl at the heart of the novel, is found in a nearby lake, a presumed suicide; but as police investigate her death, they learn that Lydia’s real life did not match the one her parents assumed she was living. She was not, as they believed, a popular girl who maintained a special place on both the honor roll and at every party, but instead a loner, struggling both academically and socially. A tender examination of ambition and family and the ripple effect the past has on the present, this novel is a heartbreaker and will feel especially resonant if you were a certain kind of teenage girl (or the parent of one).

Girls on Fire by Robin Wasserman

The girls in this book are scary and funny, loyal and devious, and together they are, as Wasserman promises in the feverish prologue, radioactive. Like Lydia Lee, Hannah is a nobody at her high school; unlike Lydia, she attracts the attention of a cool girl, Lacey, who is as edgy as Hannah is bland—but Lacey brings out a sharpness, a fire in Hannah. She introduces Hannah to Kurt Cobain and the fun of rebellion, and they bond over their mutual hatred of the beautiful and cruel Nikki, whose boyfriend Craig killed himself a year earlier. These four are connected to each other in surprising ways I won’t reveal, but I’ll say that among them Wasserman creates an incendiary tension that feels real and dangerous, culminating in an ending that really, truly shocked me and made me text my sister to tell her to read this immediately. Relationships between teenage girls are fraught, complicated, in some cases guided almost equally by love and pettiness, passion and jealousy, and Wasserman makes the friendship between Hannah and Lacey both tender and frightening.

You Will Know Me by Megan Abbott

No one writes about the psyches and complexities of teenage girls like Megan Abbott; this entire list could have been comprised solely of her fantastic novels. But I could only pick one, and as a mother who has logged many hours watching her gymnast daughter work out, I had to go with this one: Katie Knox and her husband Eric have made their daughter Devon, an exceptionally talented gymnast, the center of their world—everything revolves around Devon’s training and their shared Olympic dreams. Devon herself is steely, icy, wholly apart from her peers in the gym and at school; she is untouchable, and, as Katie learns, unknowable. When a member of their gymnastics community is found dead, everyone is shocked, but Katie watches Devon absorb the event with a cool detachment, and Katie worries about what that means about Devon and about herself as a parent. As the book unfolds, we see how Devon’s ambition, which serves her so well in the gym, is its own kind of darkness, and her parents must confront their own complicity in that. Like Everything I Never Told You, You Will Know Me explores the horrifying reality that all children remain, to a certain degree, strangers to their parents.

Marlena by Julie Buntin

Buntin’s debut novel tells the story of the lonely Cat and her intense, brief friendship with Marlena, her next door neighbor. Marlena is quick and fun, and the girls become best friends, fast. But Marlena’s world is a shadowy one, defined by neglect and want, and Cat lets herself be drawn into it, intoxicated as much by Marlena’s friendship and the accompanying adrenaline as by the drugs they take and the booze they drink. The story of Cat and Marlena is tinged with regret, a melancholy that other books about bad girls may lack: we know from the opening pages that Marlena will be dead before the end of the book, and that Cat will grow up to be an alcoholic. By framing the novel this way, Buntin reminds us of something we already know but often don’t want to confront: there are certain relationships that never leave us, and even in their brevity, continue to shape who we are and the choices we make.

Bunny by Mona Awad

The girls in Bunny are older than the other girls on this list—they are MFA students—but in certain ways are the perfect embodiment of dark girlhood. The Bunnies are a quartet of girls that Samantha, another MFA student, watches with both disgust and interest: they call each other “Bunny,” and they are exclusive, twee, saccharine. Samantha can’t stand them. But one day they invite her to join their group, and against her better judgment, she does. Then things get weirdly dangerous and dangerously weird. This book is wild, scary, and funny, nearly impossible to boil down to a few neat sentences, but I can say it’s a sharp exploration of femininity, friendship, and the creation of art.

The Girls Are All So Nice Here by Laurie Elizabeth Flynn

The title alone of Flynn’s adult debut (she has previously written two YA novels) is resonant and anxiety-inducing: who among us hasn’t been in a new place, friendless and uncomfortable, and tried to reassure ourselves that the girls really are so nice here? Ambrosia, one of those titular “nice” girls, receives an invitation to her ten year college reunion—along with an anonymous note that says, “We need to talk about what we did that night.” Amb knows she must deal with secrets from her past, the fallout from the bad things she and her former best friend, the toxic and manipulative Sully, did, but things get worse when Sully reveals that she too has received similar anonymous notes. Is someone going to take their revenge against the girls? Alternating between Amb’s time at college and the present day, Flynn reveals the darkness girls are capable of, building toward a thrillingly unsettling ending. Be on the lookout for The Girls Are All So Nice Here in March.

The Crucible by Arthur Miller

A staple of high school English classes everywhere, The Crucible features the original teenage girls not to be trifled with: Abigail Williams and her friends, the instigators of the Salem Witch Trials. Miller imagines Abigail as the young scorned lover of John Proctor, an older, married man, and in her anger, Abigail first tries to put a curse on Proctor’s wife and then, when that doesn’t work, turns her story on its head and accuses other men and women in their Puritan community of witchcraft, including Proctor himself. Miller intended his play to be an allegory for McCarthyism, but it is also an exploration of power—who wields it and why. Here we have a group of girls who suddenly possess an unearthly amount of power in a society that has never allowed it before. By the end, our sympathies extend even to Abigail, who, when all is said and done, is a heartbroken young girl who does what she can to seek her own kind of justice in a community that would never grant it for her.