If you’ve read only one book about the Spanish Civil War, chances are it’s either Ernest Hemingway’s novel For Whom the Bell Tolls or George Orwell’s memoir Homage to Catalonia. And if you’ve read only two, as to what they might be, I’d confidently push all my chips into the center of the table.

Many outside the Spanish-speaking world can be forgiven for assuming little else has been written about Spain’s bloody civil war, which lasted from 1936-1939—not one but two of the 20th century’s greatest writers penned works about it that rank among their finest. What else, then, could possibly be said concerning these three years in which Spain tore itself apart?

Plenty, of course.

Like a Paris café in the 1920’s, the Spanish Civil War drew many of the world’s premier and budding writers, poets, and artists to it, either as a correspondent or a volunteer. And, as can be imagined, they had many thoughts about what they saw and experienced from their respective positions on the Spanish map, which was oftentimes little bigger than a postage stamp. While some of these evocations of the war may seem definitive, none were comprehensive.

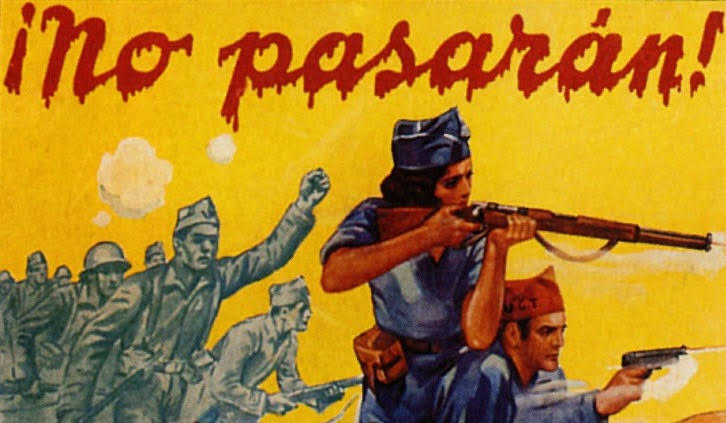

Those armed with the quill were attempting to wake a sleeping world to the threat fascism posed to the precarious peace many still enjoyed. Few felt burdened by any pretense for objectivity. What they knew in their bones, along with the thousands of International Brigadiers who would sacrifice their one glimpse at life to fight in a country not their own, is that only by stopping fascism in Spain could another world war be averted. It did not take long for history and tragedy to confirm this belief.

Two weeks before General Francisco Franco declared victory on April 1, 1939, Hitler invaded the Sudetenland. Five months later, he would order his troops into Poland and the world’s deadliest conflict would officially commence.

By then, many of the first memoirs from the Spanish Civil War were already on the shelves. The novelists weren’t lagging too far behind.

As such, my novel What We Tried to Bury Grows Here is entering a very crowded field. The novel follows a young soldier, Isidro, who leaves his home in the Basque Country to defend Spain’s democracy against the fascist-backed military coup attempt. His journey across northern Spain brings him into contact with a diverse chorus of voices. Isidro’s story soon becomes theirs, and theirs his. Despite the Spanish Republic being abandoned by the world’s democracies and despite their side losing one battle after the next, Isidro and the others continue to resist. It is this quixotic spirit of defiance and persistence embodied by those who fought on the side of the Spanish Republic we could use a good dose of today. Be it the perception of having lost or even within the conditions of losing, change remains a possibility.

As for the free world in the 1930s, the mass mobilization against fascism occurred too late, but it did occur, and they were shown the way by such dreamers like Isidro and others in the Spanish Civil War.

When I look at the Spanish Civil War, this is what shifts to the forefront. What follows are a list of books— not written by Hemingway or Orwell—that focus on other aspects of Spain’s bloody war that, tragically, served as a dress rehearsal for World War II. I limited myself to memoirs and novels that can be found in English.

In the Night of Time by Antonio Muñoz Molina, translated by Edith Grossman

Each year, Antonio Muñoz Molina’s name inches further up the list of possible laureates who might walk across the stage in Sweden. And for good reason. Rare does a year pass not graced with the presence of another new and profound book by Muñoz Molina. Most are novels and long-form essays, many defy easy categorization, like the 2014 Like a Fading Shadow, which somehow marries recollections of his early writing career with the months that Martin Luther King’s killer spent on the run – the paper-thin connective tissue is that both occurred in Lisbon. More bizarre than the conceit is that the book actually works. As impressive as his oeuvre is, it’s his 2009 novel In the Night of Time that I most consistently press into people’s hands. The novel follows Ignacio Abel, a renowned architect overseeing the construction of University City, a new neighborhood for Madrid, just as the competing and metastasizing political ideologies begin tearing Spain asunder. Politics don’t much concern Ignacio, nor does the war. He is far more interested in his architectural project, in creating and building while the world around him destroys itself. Soon enough, he gets in on the act, destroying his marriage and family life by falling hopelessly in love with a young American who is in Madrid at that time. He wants both his work and his affair to continue, but his country is at war, and try as he might, he is not allowed to live outside of his times.

The Time of the Doves by Mercè Rodoreda, translated by David Rosenthal

During the last jerky breaths of the Second Spanish Republic, Mercè Rodoreda was forced into exile, not because she had been engaged in politics but because she wrote in Catalan, which would be viewed by the new regime as a political act deserving of punishment. After two decades in exile, she wrote The Time of Doves, which remains not only Rodoreda’s most read novel but also one of the Catalan language’s. It is a hallucinatory novel – Teresa lives her life at a sort of remove – that reads at a breakneck pace. Months pass by in a clause, and if there is another novel that begins more sentences with the word “And,” I’ve not read it. No bullets fly across the page. Instead, the war arrives by heresy, by what is told to our narrator or overheard, by the garrote tightening around her life and those of her children. It’s been fifteen years since I last sat down with the novel, but what I recall are the quiet moments of a life which become increasingly impoverished by violence and the wills of men.

Savage Coast by Muriel Rukeyser

In Rodoreda’s novel, the Spanish Civil War creeps toward the page. That is not the case in the poet Muriel Rukeyser’s novel Savage Coast. It manifests as an explosion in time that does not literally derail the train that Helen, the novel’s protagonist, is on but stalls it on its tracks. Helen is traveling to Barcelona to cover as a reporter what would have been the People’s Olympiad, an alternative to the 1936 Summer Olympics that was to take place in Nazi Germany the following month. Those countries and athletes boycotting the Nazis were to participate in the People’s Olympiad in Barcelona. German exiles were among those who set to compete in the games, and at the start of the novel Helen has just had sex with one of them, Hans, who will soon join the International Brigades, as so many of the athletes would, to fight against the fascist-backed coup attempt. Helen is witness to the first days of the war, from the perspective of revolutionary Barcelona, the epicenter of Catalonia, a distinct area of Spain that would be unmatched in its concentration of revolutionary zealots. The novel, which plays with genres and was unpublished during Rukeyser’s lifetime, is one of awakenings – sexual, political – to a greater sense of a woman’s personhood in a teetering world desperate for change.

A Moment of War by Laurie Lee

Laurie Lee was another young person waking to the world around him and determined to do his part. In his memoir, Lee tells the story of leaving England and making the staggeringly perilous journey across the Pyrenees in winter to put himself on the front lines of another country’s war. Of those international volunteers like him, he writes “…we shared something else, unique to us at that time – the chance to make one grand, uncomplicated gesture of personal sacrifice and faith which might never occur again. Certainly, it was the last time this century that a generation had such an opportunity before the fog of nationalism and mass-slaughter closed in.” There is a scene early in the novel that will stay with me always. Having survived the crossing, Lee is immediately arrested by those loyal to the Republic, to be executed or given a rifle depending upon how his credentials bear out. “The Republic was in peril, and one took no risk with its enemies.” He shares his cell with another prisoner who, as the cruel poetry of fate would have it, is a Spanish male of military age who was attempting to flee what would essentially be military conscription by escaping over the Pyrenees, making Lee’s trip but in reverse. Because of this perceived disloyalty and cowardice, he will be shot. For a single night the two men share a cell, one who looked at the world around him and thought, I’ve got to get the hell out of here while another saw the same picture and started packing his bags.

Dialogue with Death by Arthur Koestler

Lee’s time in prison was brief. Not the case for Arthur Koeslter, the author of Darkness at Noon, a novel the world would have been denied had the Spanish Nationalists been just a bit hastier. Koestler was in Malaga as a correspondent at the time of its fall to the Nationalists. Despite the hairiness of the situation, Koestler chose not to flee with the masses. This decision very nearly cost him his life. Arrested by the Nationalists, he would spend the next three months in prison, never certain if or when he’d be dragged from his cell like so many others and pushed against the wall. “Long before I got to know Spain,” he tells his reader, “I used to think of Death as a Spaniard. As one of those noble Señors painted by Velasquez, with black silk knee-breeches, Spanish ruff, and a cool, courteously indifferent gaze.” That indifferent gaze is on him throughout his imprisonment (an international pressure campaign ultimately led to his freedom), but he never cracks under it. Instead, he manages to maintain a humorous perspective on his absurd predicament and the captors and captives he bonds with. “I believe the only consolation you could give to a condemned man on his way to the electric chair would be to tell him that a comet was on the way which would destroy the world the next day.” Fascism might be a nightmare let loose upon the land, but the terrifying thing about the men under its sway, like Koestler’s captors, is just how banal and familiar they are.

Cry, Mother Spain by Lydie Salvayre, translated by Ben Faccini

Lydie Salvayre was born and raised in France, the child of Spanish exiles from the war. In her novel Cry, Mother Spain, she is at once reviving her mother’s story of her youth, “rescuing it from the oblivion to which it has been consigned,” while also reflecting upon her reading of George Bernanos’ memoir The Great Cemeteries Under the Moon, all while caring for her elderly mother and considering the book she is writing. Bernanos was a French citizen, a veteran of WWI, and a writer greatly concerned with the spiritual decline of his times. After the failed coup in Spain and the outbreak of war, Bernanos supports the fascist Falangist party, which is backed by the Catholic Church. However, after witnessing Falangists commit atrocity atop atrocity, he “could no longer ignore what his Catholic pride was refusing to concede. It was now as clear as day: in remote hamlets and villages, men were being rounded up every night as they came home from the fields.” Their crime is to be in Spain in 1936, a time when “what was hugely important, desperately and intensely so, in fact, was to classify people as good or bad, according to their political labels.” This is the Spain that Salvayre’s mother finds herself in at the age of 15. Her older brother – Salvayre’s uncle – has just returned to their village from Lérida, where his head was filled with new revolutionary ideas. In the village, a village “where all lives are pre-determined,” he is “a dark angel fallen from the sky,” while he insists to his fellow villagers that they “can live differently. It is possible.” Salvayre’s mother is convinced. She was born to become the humble maid of a wealthier family were it not, she tells her daughter, for her “sheer good fortune…War broke out the next day and I never went to work as a maid for the Burgos family, or anyone else for that matter. The war, ma chérie, came in the nick of time.”

Lord of All the Dead by Javier Cercas, translated by Anne McLean

In Lord of All the Dead, Javier Cercas returns to the subject of Spanish Civil War. In his surprising break-out novel Soldiers of Salamis, Cercas documents his attempt (or the attempt of a character with the name Javier Cercas) to tell the story of a Falangist soldier who narrowly escapes being executed by firing squad at the end of the Spanish Civil War, while searching for the Republican soldier who allowed this escape. The exhumation of the past hums along, stalls, hits a wall, then receives help from none other than Roberto Bolaño. In Lord of All the Dead, Javier Cercas (or, again, a character with the name Javier Cercas) tries once more exhuming the story of a soldier from the Spanish Civil War. This time it is the story of Manuel Mena, the great-uncle to both Javier Cercases, who falls under the sway of fascist ideas and enlists at the age of 17. He will die two years later during the Battle of the Ebro. Cercas knows little else of this man whose absence created a lacuna in the family. With Lord of All the Dead, he repeatedly tries and fails to fill it in and to understand why his great-uncle was willing to die fighting for an unjust cause, “for interests that weren’t even his.” Cercas receives assistance from the filmmaker David Trueba, who adapted Soldiers of Salamis for the screen and directed the film and who has also recently lost his wife to a very handsome and very famous actor (the identity is revealed late in the novel). As with Bolaño in Soldiers of Salamis, Trueba prods Cercas along. “We don’t judge Achilles by the justice or injustice of the cause he died for,” Trueba tells Cercas, “but for the nobility of his actions, by the decency and bravery and generosity with which he behaved. Should we not do the same with Manuel Mena?…Look, Manuel Mena was politically mistaken, there’s no doubt about that; but morally…would you dare to say you’re better than him? I wouldn’t.”

The Tree of Gernika: A Field Study of Modern War by G.L. Steer

Had he lived long enough to write more books, perhaps G.L. Steer would need no introduction. Born in South Africa, he was a fearless British war correspondent who loathed the world’s bullies and who also happened to be one of the finer crafters of sentences of his time. I leaned so much of my weight on The Tree of Gernika during the writing of two chapters in my novel that he deserves a co-writing credit for them. Looking at The Tree of Gernika now, I’m surprised I ever had the moxie to venture into territory already treaded by Steer. There is no way to improve upon the descriptions found in here of those months of war in the Basque Country. It is astounding all that Steer witnessed and participated in and survived. Then, while the war still raged elsewhere in Spain and international public opinion could still be swayed and galvanized, he sat at his desk and wrote not in rushed wire-like dispatches but instead took the time to shape sentences dizzy with the sort of poetry of a Melville or Fitzgerald. Ironical and stiff-upper-lipped, his prose could be beautiful in the horror that it described, like when an “air-maddened” mob attacked a prison in “the diseased, yellow light of the rationed electricity of Bilbao,” or when a “fearful explosion” produces over the ridge “a heavy cloud of Scotch mist.” Watching bodies pulled out of the wreckage of a destroyed building he notes how “a whole family of the past and future [were] wiped out by one bomb. Their hair lay wet and straggly over their bruised faces, hung in damp black slabs of gauntness as they were carried away.” And, of war in general: “Every war can be described as a series of colossal idiocies culminating in defeat.” Though a work of war correspondence, Steer is present on nearly every page. He was in the Basque Country from the beginning to the bitter end, shot at repeatedly, sought cover in craters, and nearly bombed out of creation a few times. He was the first to report on the destruction of Gernika, a report that Picasso would soon read translated into French and which would inspire his greatest work of art. Before European fascists had fully concentrated their homicidal attention on the Basque province of Bizkaia, Steer left Spain briefly, crossing the border into Biarrtiz, France, where his pregnant wife had fallen ill. By the time he arrived, she was dead, as was their unborn son. He returned to the war stripped of any concern for his own life. With the bombs falling around him, twenty thousand a day toward the end, Steer bore witness to the full immensity of this “very human tragedy [of] the destruction of man by a system, of spirit by routine.”

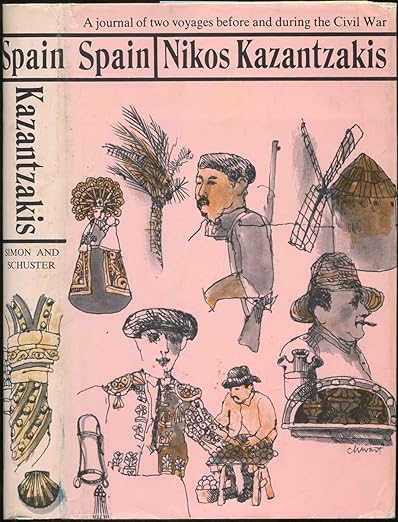

Spain: A Journal of Two Voyages Before and During the Spanish Civil War by Nikos Kazantzakis, translated by Amy Mims

Nikos Kazantzakis is well known for novels Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ, but he produced a staggering body of work, practically all of which was translated into English but is now out of print. Among these works are novels, verse (his opus is a sequel to The Odyssey), memoirs, plays, spiritual exercises, and travel books, one of these being Spain, which saw him journeying into Spain as a reporter just as civil war broke out. Unlike so many other intellectuals, Kazantzakis happened to be behind Nationalist lines most of the time he was in the country. He lived his life with an almost anachronistic spiritual passion and possessed tireless curiosity and the sort of deep compassion for all creation that could fracture most hearts. When you open a book by Kazantzakis, the world burns with such traits. With few exceptions, the Spain that Kazantzakis entered in 1936 outmatched his roaring fervor. When he crosses paths with a man dragging a dog yelping in pain, he stops the man to ask about the dog. The man laughs and shows him his work. “When I bent down what did I see? A cross branded there with a burning iron…The fanatic peasant had forced even his dog to turn martyr for the Catholic religion.” Kazantzakis reports on the Siege of the Alcazar and walks among its smoldering ruins. He is witness, as well, to the Nationalists’ multiple attempts on Madrid, never turning away from the nightmare before him. “In spite of longing to get away, I forced myself to stay there: to watch; not to lose a single drop of the horror. A stretcher arrived. The soldiers bent over and handful by handful scooped the human pulp onto the stretcher.” These “horrifying spasms of torture” that Kazantzakis bears witness to has him observe that “we have entered on an historical era of the insanity of the human race. As happens at critical moments in the evolution of plants and animals, the same insanity is observed throughout the species: anarchy, anxiety, illnesses, short-lived monsters, strange types, until, after much agonized exploring, a new, more perfect species is established; and so life progresses.” One must do much more than hope.

Read the original article here