If you search the internet for “books about bipolar disorder,” the overwhelming majority of titles that appear are guaranteed to be self-help books to guide you (or your loved ones) through what is seen as a scary, unpredictable illness. It’s no wonder that manic-depressive symptoms have long been used as a dramatic plot device, or that most literature around bipolar disorder is dedicated to “fixing” or overcoming it. But what if there were more creative and engaging ways to capture the beautiful electricity of our brains?

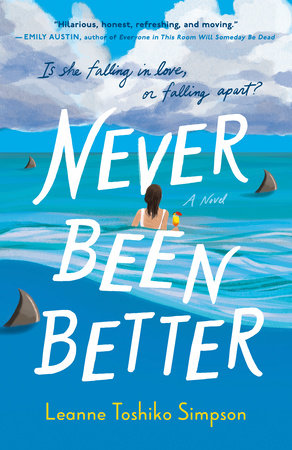

When I introduce my debut novel Never Been Better as a bipolar comedy, I’m often met with a healthy dose of skepticism. But hear me out—a year after their discharge from a psych ward, two former floormates embark on a whirlwind destination wedding (with their rapidly unravelling third wheel determined to ruin it). It’s about how we are so accustomed to a certain type of happy ending when it comes to love and recovery that sometimes we can sabotage our growth in the process—and give wedding speeches that absolutely no one asked for. Being able to laugh at the mistakes I’ve made when screaming manic or puddle-state depressed has been key to my own recovery, and I think that writing a book that chaotically hovers in the grey area between sick and well is actually more representative of how living with chronic illness feels.

Even though I do own a shelf of bipolar workbooks (mostly instructive gifts from family members), I’ve put together a list of reads that write bipolar differently—whether they’re genre-bending, subverting narrative expectations, or just hilariously relatable for anyone living with mental illness. It’s hard to capture the landscape of a disorder that touches the depths of human emotion in both directions, but these books do it in a way that pushes the artistic boundaries of recovery stories as we know them.

An Unquiet Mind by Kay Redfield Jamison

When I was diagnosed with bipolar disorder at 17, my psychiatrist recommended that I read An Unquiet Mind, an unusual, landmark memoir that documents manic-depression from Jamison’s dual perspective as a leading medical authority on the illness and someone living firsthand with its volatile symptoms. While the story of her immense success in the field offered early hope that my diagnosis could be more than just a limitation, what stuck with me the most was how lack of insight—a hallmark of mania—could impact even the most educated and experienced of patients. It helped me trust my loved ones a little more and forgive myself for missing early signs of illness.

Touched with Fire by Kay Redfield Jamison

It was years later when I discovered her memoir’s predecessor, Touched With Fire, which explores the relationship between art and madness by tracking the creative work, diaries and family trees of artists such as Woolf, Hemmingway, Shelley and Van Gogh. She argues that artists in particular have been associated with madness, and the tension between their changing moods offered creative significance to their work. One of the questions I get asked most often as an openly mad writer is whether my medication and strict wellness routines limit my creativity—and that’s when I tend to think about the detailed charts Jamison includes, marked by depressions, dangerous impulsivity, and suicides. No matter how alluring my manic creativity may feel, I always write by the rule that it’s nearly impossible to finish anything—brilliant or not—if you can’t take care of yourself while doing it.

The Silver Linings Playbook by Matthew Quick

As the only book about bipolar disorder that my doctors deemed “light enough” to read in the psych ward, Matthew Quick’s breakthrough mental health dramedy will always hold a special place in my heart. The Silver Linings Playbook is driven by the endearing (if slightly unreliable) narration of Pat Peoples, a former teacher recently discharged from a Baltimore psychiatric hospital who is attempting to get his life back together and end “apart time” from his estranged wife. His rather zealous self-improvement routine lands him in close proximity with Tiffany Webster, a recent widow who follows Pat on his runs and offers to deliver contraband letters to his wife in exchange for his partnership in a dance competition. The zany humor of this novel – which includes riotous Eagles tailgate parties and numerous outbursts triggered by the smooth jazz of Kenny G. – offers a compelling balance to the seriousness of Pat’s plight. It’s a book that doesn’t pull any punches when exploring the impacts of mental illness, but delivers a feel-good ending that offers hope for readers who may be stumbling through their own recoveries.

Heart Berries by Terese Marie Mailhot

I have read the opening chapter of Heart Berries more times than I can count. An experimental memoir that tracks Mailhot’s movement from the Seabird Island Indian Reservation in British Columbia to the pressure of creative writing school to a hospitalization for bipolar II disorder and PTSD that pushed her to become a “woman wielding narrative,” her prose grips you from the very start. The New York Times called this book a sledgehammer, but it’s much more precise than that. The skillful and introspective fragmentation of a difficult narrative captures what is so hard to explain coming out of the psych ward – that memory and imagination can play tricks on us, and often what we need to survive our pasts is to find new ways to narrate our futures.

Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo & Me by Ellen Forney

By pairing bold illustrations of a mind on edge with comedic and clear-eyed commentary (plus a philosophical crisis over the nature of creativity), Ellen Forney’s Marbles is the perfect graphic memoir for mad artists. Driven by the fear of losing her creative spark while on medication for bipolar I, Forney trashes her treatment routine before finding herself losing her grip on life instead. She turns to the histories of temperamental artists—and the work of scholars like Jamison—to figure out if taking care of herself means choosing to be less creative. While illustrating her highs and lows, Forney pushes back against the romanticization of artistic madness with wit and wisdom while acknowledging the many roads we can take to creative fulfillment.

I’m Telling The Truth But I’m Lying by Bassey Ikpi

This New York Times bestselling memoir-in-essays follows Bassey Ikpi, a Nigerian American slam poet, as she digs through the roots of her eventual hospitalization for bipolar disorder II. What I love about this collection is that it refuses a singular understanding of her story—Ikpi brings together the influences of culture, family, failed relationships and artistic ambition to highlight the many ways she has lived through her illness. One standout chapter titled “What If Feels Like” is some of the most vivid and accurate writing around mania that I have ever seen—I remember reading sections to my partner out loud in the dead of the night and feeling so much resonance in her avalanche words. It is a vulnerable, brave and kaleidoscopic collection that is such a creative departure from the scaffolding of most recovery narratives—it’s a true testament to Ikpi’s power as both a writer and an advocate.

Juliet the Maniac by Juliet Escoria

Juliet the Maniac is an ambitious, piercing and often darkly funny book that leans heavily into autofiction and offers unflinching intertextual glimpses into a manic-depressive life. At fourteen, Juliet is a successful honors student gunning for an Ivy League acceptance, trying to swallow the feeling that something is mutating inside of her. After spiraling into self-harm, drug use and attempted suicide, Juliet is sent to a controversial therapeutic boarding school called Redwood Trails to recover from what is diagnosed as rapid cycling bipolar disorder. The relationships that Juliet develops at Redwood are alternately affirming and self-destructive, but what seems constant is a system that repeatedly fails the young people it is entrusted with. This would have been a difficult book to read as a teen just entering mental health care, but years later, I can’t help but appreciate its candor. The scattering of mementos from the author’s life throughout the narrative—such as Escoria’s hospital bracelet, a get-well card, newspaper clippings on Redwood and letters to a future Juliet—help frame a frightening story within the gentle wisdom of her later self, one that has seen the other side and decided to stay.

The Collected Schizophrenias by Esmé Weijun Wang

This breakout collection of essays begins with Wang discovering she has been misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder, and has actually been experiencing schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type—placing her inside “the wilds of schizophrenias,” which comes with increased stigma and surveillance. While schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder are different illnesses, I’ve included Wang’s work on this list due to her insightful descriptions of what she calls sensory distortions (also known as hallucinations), which occur for some bipolar people experiencing mood episodes. Many of my favorite essays within The Collected Schizophrenias pull apart the idea of credibility—in particular, “High-Functioning” and “Yale Will Not Save You” explore Wang’s strategic habit of offering “signifiers of worth,” such as her education, wedding ring, and strict treatment plan, while feeling doubly aware of her vulnerability. People living with hallucinations are often hyper-visible in public spaces, and Wang’s candid reflections on using her glamorous appearance and credentials as armor offer a complex interrogation of the invisible hierarchies of mental illness that society is organized around.

Rx by Rachel Lindsay

Rx opens with the classic conundrum of a mad artist taking a stable corporate advertising job just to obtain health benefits (haven’t we all been there?). But when Rachel Lindsay is offered a high-profile account that requires her to sell the psychiatric medications she’s secretly been taking for years, she swerves into mania and finds herself hospitalized against her will. Lindsay’s graphic memoir—started during the very hospitalization she recounts—is hands-down the funniest and most relatable depiction of bipolar disorder I have come across, including a hysterical full page depiction of the psych ward entitled “Club Meds.” But as she tries to put her life back together, Lindsay writes, “If only I had known, during my darkest days in the ward, that the hospitalization would lead me to exactly the life I felt so viciously denied.” Bipolar folks have a long history of trying to fit themselves into unforgiving boxes for other people’s comfort. Lindsay’s story is a moving and much-needed reminder that sometimes we need to carve our own paths outside the ordinary to be able to survive.

Read the original article here