Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

Comics aren’t what people usually think of as revolutionary texts–but, in reality, many graphic narratives are deeply rooted in political movements and social commentary. Whether it has been war propaganda that caricatured the “enemy” (such as Dr. Seuss’s racist cartoons) or graphic novels that were banned for speaking out against the government, the combination of word and imagery has proven to be popular, powerful, and often political. This isn’t a coincidence; the genre’s so-called “triviality” can help it to escape censorship.

So how does this tie together with translation? Translator Genevieve Guzmán writes that translated graphic texts offer a chance to “communicate cultural awareness to a global audience,” as well as “highlighting the political and cultural questions a more autocratic government may wish to keep buried.” Translation is also a way of controlling literary power, as writer Jen Wei Ting notes; it’s a choice to decide what stories to put on the global stage. Translated graphic narratives can help illustrate (we can’t ignore the pun here) a fuller picture of nations, histories, and cultures beyond a snappy headline.

Translated from many different languages, these recently published graphic novels below all call attention to—and speak out against—various systems of inequality. With that said, there is a vast range: some are more focused on social issues, such as humorous takes against the patriarchy or stigmatization of depression. Others offer a sobering look at human rights violations, such as human trafficking and genocide.

Grass by Keum Suk Gendry-Kim, translated from Korean by Janet Hong

The issue of Korean comfort women—those who were forced into sexual slavery for the Japanese Imperial Army during WWII—continues to be a point of contention between Japan and South Korea. Based on Gendry-Kim’s interviews with survivor Ok-Sun Lee, Grass is a powerful non-fiction graphic narrative of the nation’s historical trauma. Lee was born into a poor Korean family when Korea was annexed by Japan. When Lee was 15, she was kidnapped to become a “comfort woman” and provide “service” for the Japanese soldiers—or, euphemisms aside, forced through numerous sexual abuse. Done in black ink, which ranges from thick brushstrokes to depict traumatic memories and detailed landscapes of Korea, Grass is an adamant testament to the horrors of war.

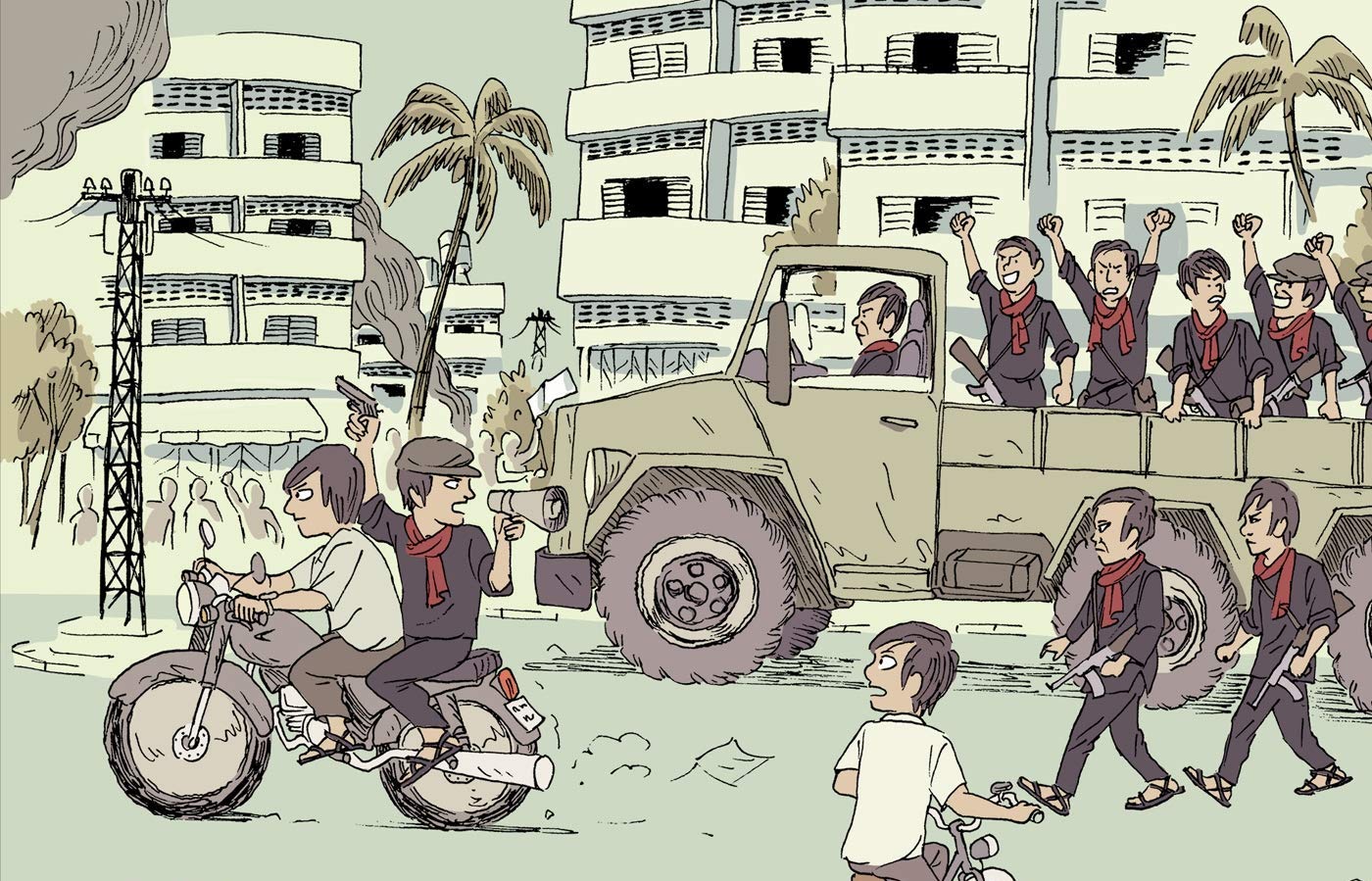

Year of the Rabbit by Tian Veasna, translated from French by Helge Dascher

Tian Veasna was born three days after the Khmer Rouge seized power in 1975, unleashing a genocidal reign of brutal work camps, mass murders, and human rights atrocities—leading to the deaths of nearly a quarter of the Cambodian population. Veasna interviewed his parents and relatives for first-hand accounts, and forgoes first-person narration in the book. Drawn in muted colors and loose lines, the book focuses on a chronological account of the various family members’ struggles, interspersed with short historical contextualizations about the Khmer Rouge’s regime. Veasna’s family, originally affluent before the takeover, is sentenced to labor camps; eventually, they must flee Cambodia. A decades-spanning saga, Year of the Rabbit is a harrowing, personal look at the lingering effects of the Cambodian genocide.

Goblin Girl by Moa Romanova, translated from Swedish by Melissa Bowers

Bad Tinder dates, failed ghosting attempts, and abuse of power: Romanova’s autobiography provides a spiky and darkly humorous snapshot of uneven gender roles today. Her narrator—a young female artist struggling with depression and panic attacks—attracts the online attention of a wealthier, older, and well-established celebrity; he offers to be her emotional and financial “patron,” an initial source of stability for the narrator. Drawn in a semi-surreal, retro style with elements of the absurd, Goblin Girl is a relatable exploration of mental health issues and toxic power dynamics.

Freedom Hospital: A Syrian Story by Hamid Sulaiman, translated from French by Francesca Barrie

Yasmine, who lives in a small town in northern Syria, starts running an underground hospital with a group of doctors, supporters, and patients. As Bashar al-Assad’s reign becomes increasingly violent and erupts in civil war, things get complicated for the “Freedom Hospital” and its community. Sulaiman’s illustrations—done in black and white with bold, stark lines—don’t hold back from extremely detailed scenes of human suffering (as this depicts a makeshift hospital in a war-devastated land, be prepared for graphic violence), but there are also burgeoning romances and soccer games. Sulaiman offers a portrait of Syria that moves beyond simply condemning Assad’s brutal regime; rather, Freedom Hospital attempts to show the complexity and nuanced personal tragedies of the Syrian civil war.

Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. The Patriarchy by Liv Strömquist, translated from the Swedish by Melissa Bowers

Did you know menstrual blood was used as a love potion? Are you curious about modern-day labial surgery? Strömquist’s lively, X-rated graphic novel blends feminist theory with a biting sense of humor. Fruit of Knowledge zeroes in on female genitalia–and its stigmatization from ancient times to today; through clunky line drawings and occasional photographs, it entertainingly depicts the ways in which vulvas, vaginas, clitorises, and menstruation have been addressed by society. The most engaging part of this feminist discourse is Strömquist’s cartoon avatar, who sports a wiry ponytail that defies gravity and provides endlessly clever narration.

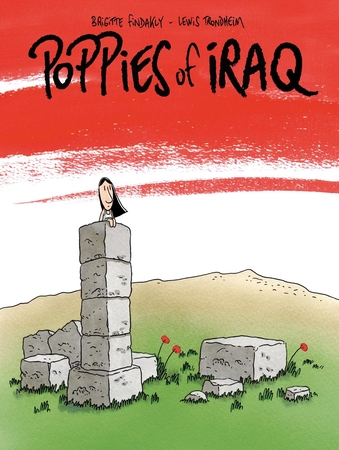

Poppies in Iraq by Brigitte Findakly and Lewis Trondheim, translated from French by Helge Dascher

If you loved Marjane Satrapi’s poignant take on her Iranian childhood in Persepolis, Poppies in Iraq is another tale of growing up under an oppressive regime in the Middle East. This much-acclaimed graphic memoir depicts Brigitte Findakly’s childhood and was co-written and illustrated by her husband Lewis Trondheim with whimsical, rounded watercolors. Findakly grows up amongst the increasingly brutal changes in Mosul under Saddam Hussein’s reign; eventually, her family decides to immigrate to Paris. Findakly and Trondheim are adept at depicting nostalgia for family events–like picnics by archaeological sites–while recognizing that many of these previous childhood haunts have been destroyed. Amidst its historical context, Poppies in Iraq is a touching family portrait and an exploration of one’s connection to their childhood home.

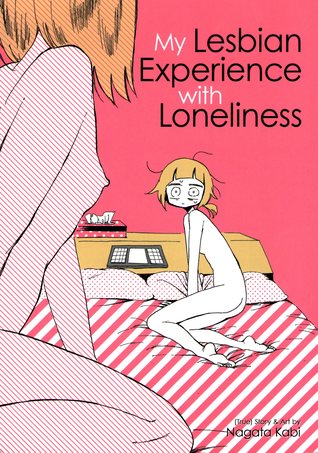

My Lesbian Experience with Loneliness by Kabi Nagata, translated from Japanese by Jocelyn Allen

An internet cult hit, Nagata’s autobiographical narrative is about a young Japanese woman’s struggles with her mental health and sexuality. Kabi has dropped out of university; amidst eating disorders and depression, she struggles to find a purpose in life. As she reads erotic manga for boys, she comes to realize that she is attracted to women (despite same-sex marriage gaining more support in Japan, it is still illegal and societal views often remain restrictive on LGBTQ+ movements). With minimalistic artwork—spindly characters, little background, and sparse shading—Nagata leaves ample room to explore the convoluted, agonized journey of her narrator’s headspace. Kabi’s heartfelt story continues in sequels, My Solo Exchange Diary.

The Winter of the Cartoonist by Paco Roca, translated from Spanish by Andrea Rosenberg

Roca’s well-researched graphic novel centers on a real-life group of five cartoonists in 1950s Spain, as they fought to protect their rights as artists and workers against Editorial Bruguera, one of the largest publishing houses in the country. Instead of staying under restrictive conditions at Editorial Bruguera, these cartoonists choose to start their own magazine, dreaming of creative freedom. Drawn in a detailed, pseudo-realistic style, The Winter of the Cartoonist poses thoughtgul questions about labor conditions, artistic agency, and licensing rights.

Perramus by Alberto Breccia and Juan Sasturain, translated from Spanish by Erica Mena

The winner of an Amnesty International Human Rights Prize, Perramus was an act of rebellion when it was first created during the Argentinian military dictatorship of the 1980s. The protagonist, Perramus, is a political dissident who joins forces with a gruff Uruguayan, a foreign pilot, and Jorge Luis Borges (real-life author of The Library of Babel fame). Add in encounters with a circus guerilla movement, a Henry Kissinger stand-in, and a tango singer’s skull—Perramus is both a call for revolution and a masterpiece of dark humor. Through the absurd adventures of this ragtag team, Breccia and Sasturain acutely satirize Argentinian politics and U.S. imperialism.