Electric Lit is committed to publishing—and paying writers—through the pandemic without any layoffs or pay cuts. Please consider supporting us during this difficult time. Donate here.

.

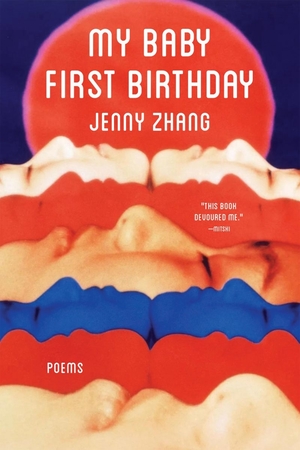

When Jenny Zhang’s debut short story collection, Sour Heart, was published in 2017, I had been reading her poetry, short-fiction and essays for a few years and I felt I’d discovered a writer who was speaking to me alone, who had invited me into her obscene and bold and wildly playful dreams.

Zhang herself refers to the poems in her second full-length poetry collection, My Baby First Birthday, as dreams: dreams for a world in which mistakes are celebrated and language distorted and ugliness and beauty collapse into each other inextricably. The poems in this funny and piercingly beautiful book interrogate notions of innocence and childhood, the fetishization of motherhood and femininity, and the ways in which imagination, humor and delight can be tooled to critique the obscenities of white supremacy, patriarchy and global capitalism. These poems ask: what does it mean to be someone in the world when none of us gave consent to be born? Who, in our society, is allowed to be nurtured and cared-for and innocent, and who is deprived of this experience? But as infuriated as these poems are with our abject and chaotic world, they are also fiercely tender and loving and hilarious, invoking friendship and love and mutual care. “I ASKED YOU TO REACH OUT,” Zhang writes, “AND TOUCH ME RIGHT THERE …/ YES THERE.”

In our phone call, Zhang and I discussed language and dreams, play and innocence, and what it means “to be baby.”

Roberto Rodriguez-Estrada: Much of your work is concerned with language — how you had to learn a second language when you moved to New York City at five, and your parent’s and your relationship to English. There are also so many ways in My Baby First Birthday that you make language a sort of playground. For instance, the ways the word “goo goo” comes up frequently. What does “goo goo” mean to you?

Jenny Zhang: That’s a really cool question… I never thought anyone would ask me about “goo goo.” I guess it is a sort of shorthand for babbling and I happen to like babbling as an actual sound that little babies make and, I think, also as a concept. Babbling is what babies do when they’re trying to communicate but they can’t do so in a way that people can comprehend, so it can just be dismissed as garble or cutesy. But I think babbling is one of the earliest forms of expression, or one of the earliest forms of communication that a lot of us try.

I think a lot of people have been wanting that, people who have been disbarred from innocence, or who never got to be innocent and never got to be a baby.

I also got really obsessed with the idea of being a baby, of being baby. I know that idea was a big thing last year and I think it’s probably because as a culture everything felt so corrupted that there was a fetishization of returning to innocence, which we wanted collectively as a culture. But I think a lot of people have been wanting that, people who have been disbarred from innocence, or who never got to be innocent and never got to be a baby, and that includes, I think, a lot of marginalized folks who are treated as guilty or dangerous from a very early age. I think all these people have been longing for babyness a lot longer than our collective culture and society has been. So I started writing and felt that I was babbling a little bit, which is to say I didn’t feel like I had mastery over poetry, I didn’t feel like I had learned it, I didn’t feel like I had gone to the depths of learning it the way other people I knew had. And maybe that’s not true because I’ve been through all these different institutions yet somehow I still came out of it feeling pretty dumb and I didn’t feel fluent in poetry or poetics. “Goo goo” felt like the best encapsulation of trying to express something in an imprecise way.

RRE: Infants and birth and motherhood are recurring themes in this book. The speakers of these poems are constantly interrogating what it means to be born, what it means to be someone in the world. What prompted this inquiry?

JZ: There was a period in my life where I felt really trapped because I felt like the first thing that ever happened to me was that I was born and I never consented to that. No one ever asked if I wanted to be born into this world. No one ever really asks anyone, it just happens. And because I was so disappointed by the world that I was born into, I just felt so trapped, like the only way out would be to end my existence, but I didn’t necessarily want to stop existing. What I wanted was to have never existed in the first place so I would never have to be put in the situation of having to make that choice. And I felt very troubled by that, and saddened by that. I guess I was just concerned with that question.

No one ever asked if I wanted to be born into this world. No one ever really asks anyone.

Then I also felt like I was at an age where I was ripe for motherhood, where I could have become a mom, but I also felt like: how can I subject another human being to what I’m subjected to, which is being born, if I don’t know if they would want that or not. Again it really troubled me because I as an individual could perhaps do the best job possible of mothering a child but I couldn’t change the world as an individual and a child that I hypothetically gave birth to would have to interact with the world. It made me feel I guess trapped is the only word I have, and at the same time I was really grateful for having experienced the world. I don’t know I sound like someone who had just watched Waking Life and smoked pot for the first time and was grappling with all kinds of existential crisis — but I also felt like I wasn’t able to graduate from that sort of adolescent existential crisis in some ways that other people seemed to have graduated from, I felt like I was still stuck in that. So I guess I started writing these poems to play around with these ideas and almost get them out of my system — of course nothing ever gets out of your system.

RRE: I think a lot of people relate to that experience, especially as teenagers when we say all kinds of hurtful things to our parents like: I wish I’d never been born! Or I hate my life!

JZ: Life is seen as a gift and that’s something we’re not always willing to interrogate. First of all, not gifts are wanted and not all gifts are received consensually and not all gifts are given without any strings attached. Most gifts are given with expectations, which I guess you could argue that’s not really a gift. And I think as a teenager, I did say all kinds of stuff to my parents. It probably was really cruel because motherhood is such an idealized state of being and we idealize mothers as naturally nurturing and wanting to give their time to the rearing of a child, and we sort of drag anyone who doesn’t want to do that or can’t do that to its fully idealized capacity. There is a way in which we expect mothers to sacrifice so much of themselves, emotionally, physically, and spiritually once they have a child, and then for the child to be like, I never wanted this; it is such a blow. So I understand both sides on some level. I guess that is the paradox. I think I was also obsessed with notions of sainthood, and that we assign sainthood to the highest ideas of femininity and martyrdom, and this idea of not wanting to be saved, which is a corollary to not wanting to be grateful. It’s all still very murky for me because I’m constantly caught between being grateful still and then rebelling and being mad that anyone ever did anything that I have to be grateful for. It feels like my brain has been colonized by that expectation and I don’t want to repeat patterns that were limiting for me.

RRE: The characters of your story collection Sour Heart are mostly young girls and, in your poems, the speaker often has a bit of a playful, child-like voice. Can you talk about the role of play in your life? Both as a child and now as a writer?

I think poetry has been a place for me to recreate a dream that maybe never was, where language could be a source of play and delight.

JZ: There was a brief period of time where I learned how to speak and all I wanted to do was entertain myself and others. It was such a delightful thing, I was finally able to control making other people laugh and making myself laugh. And it was such a fun and innocent time in that way just because I hadn’t been alerted to the ways I could hurt or oppress other people or oppress myself with language. It was a defining time when I moved form China to America and I didn’t have language anymore, and the act of acquiring language was a chore and it was a fraught experience, because it was all about proving I wasn’t dumb, rather than trying to entertain others. Or if I was entertaining others it was beyond my control, because other people were laughing at me. I think poetry has been a place for me to try to create a bubble, to create a dream, to recreate a dream that maybe never was, where language could be fun and it could be a source of play and delight, and it’s not a shameful thing to be “wrong,” and it’s actually really fun. I have to pay homage too, there’s poetry all around, not just in poetry. It’s often black and queer and POC spaces that have fucked the most with language, and that fucking with language then trickles down to the mainstream and eventually everyone is saying “it’s lit” or something—that’s the way in which language evolves. Someone first had to fuck with it and have the gall to use it in the “wrong” way. I am in awe of that process, but I’m also aware that the people who start fucking with language are always the people who get criminalized and chastised for it. Then somehow white people get a hold of it and it’s fine and fun. I wanted to create a dream where it was fun from the beginning.

RRE: There’s a way your poems can, at first, cast a sort of coyness and candor and they also oscillate between that playfulness and explosive moments of gorgeous, celestial awakening. I’m thinking about the turn at the end of “yr pubes are everywhere” or throughout “i keep thinking there is an august.”

JZ: I think epiphanies often come on the heels of extremely petty and trivial things, and I don’t mean that in a literary sense or in a spiritual sense, but maybe just sudden realizations come on the heels of something stupid. And sometimes the more stupid something is the more profound it becomes.

Sometimes the more stupid something is the more profound it becomes.

I was also thinking about humor and humor as a defense mechanism, humor as a way of expressing pain. There have been times when I’m making fun of myself with a friend and I’m laughing at myself and basically dragging myself, and then later I’ll be hurt because the friend would laugh with me and I’m like: No! You were supposed to see that I was screaming out in pain through a joke, why did you not see that? And I think there’s something really inaccessible about true true true, deep deep deep pain, because in order to access it and show it, you’d have to be so vulnerable, and you have to feel safe to be vulnerable, and not have had a history of being attacked for showing vulnerability and pain, which is pretty rare, especially as we get older. There’s also a way in which I wanted to be glib sometimes and mimic the ways that we access things that are deep, which is sometimes through being very superficial and joke-y.

RRE: I read in an interview you gave a few years ago that repetition is something that draws you to poetry. Repetition in these poems allows them to gather momentum and it works so effectively. It reminds me of Gertrude Stein who says: “always repeating is all of living. everything in a being is always repeating.”

JZ: I love that Gertrude Stein quote. I’m really interested in the ways human beings are doomed to repeat and how each time we repeat something it’s never the same, it’s actually transformed with every repetition and with every cloning of that instant. So maybe it’s some kind of spiral and not just a circle you’re retracing, even if it feels like it. I think there’s also a way we repeat things to convince ourselves of something that’s not true, like I’m fine I’m fine I’m fine, and over time it sounds like a cry for help. But there’s also a way in which people of color and LGBTQ people have to keep saying the same thing over and over and over again. And it’s very fraying to say the same thing over and over again. It’s also very enraging. There’s a way in which saying the same thing can build up a lot of rage and unleash a lot of rage, and there’s a way in which saying the same thing over and over can lead to a petering out and a giving up. Of course as I was writing these poems, I wasn’t necessarily thinking of all these things. But also too as I’m writing I sometimes don’t know how to end things. It’s always interesting to me, human beings don’t get to live through their own endings, the ultimate ending of death—I don’t know what will happen, if I’ll remember it, I don’t know if I’ll come back to report what happened—and I think there’s a way that translates to poetry, so sometimes I’m mimicking what it feels like to fall asleep at night, where my thoughts are circling and circling and circling and then I pass out.