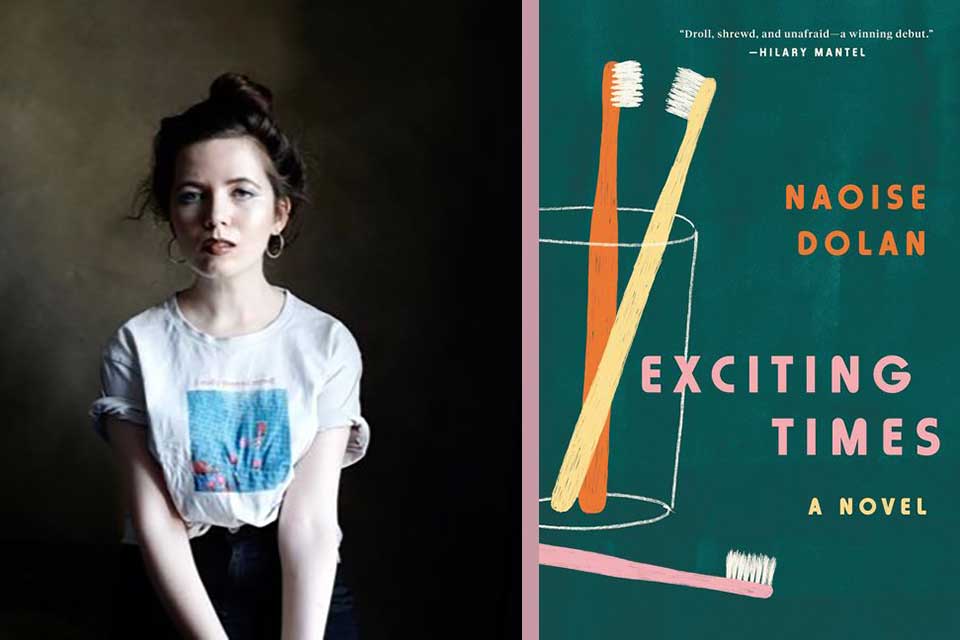

Naoise Dolan probably wishes her debut novel, Exciting Times (Ecco, 2020), wasn’t so relevant. Although the book isn’t set during a global pandemic, it does include the many unsavory aspects of millennials’ lives that usually dominate the news: the characters endure unstable and uncomfortable housing arrangements, romantic relationships that lack all human warmth, and jobs that distance them so far from their personalities and values that they feel like different people while doing them. It is not in spite of these qualities but because of them that Dolan’s work is so delightful to read.

Much of the delight stems from Dolan’s narrator, Ava, who has the ability to make harsh self-criticism and overthinking rather engaging, if not charming. She often wonders if she “cared more about my interior life than the tangible one” and if this is why she has become a “TEFL waster,” working at an English school that “only hired white people but made sure not to put that in writing.” A lot of time is spent inside Ava’s head, which should be unpleasant but isn’t: the narrative tone is depressive and biting, and she rarely spares herself. “At work I imagined nice things that might happen to me if I were a different person. When I realized I’d been daydreaming, I’d start correctively listing things I disliked about myself. The children wrote essay plans and I thought: flat feet, doughy hands, clumsiness, moral cowardice.” Plenty of us have probably made similar lists, but not many are creatively cruel enough—honest enough?—to include “moral cowardice” on the list of our own shortcomings. If the similarities to real life have the potential to make her inner monologue depressing, it’s the determination to take self-critical nagging a step further that makes them funny.

If the similarities to real life have the potential to make Ava’s inner monologue depressing, it’s the determination to take self-critical nagging a step further that makes them funny.

It’s possible to read the story as an indictment of hook-up culture: after moving from Ireland to Hong Kong, Ava soon moves in—“temporarily”—with an English banker she’s been hooking up with. According to Ava, her ability to manage the right tone with men is her most valuable skill. “I wasn’t good at most things but I was good at men, and Julian was the richest man I’d ever been good at.” From Ava’s perspective, the success of their relationship doesn’t reflect well on either of them. The two of them are “twisted individuals successfully mated, like Noah’s Ark for sociopaths.” Their relationship, or maybe the lack in each of them it represents, is in many ways the center of this book. Circling around this void like a galaxy, in typical couple-formation novel logic, is Ava’s other romantic option. Her alternative love interest, Edith, is genuinely better both in her own right and as a potential partner. “Before I met her I’d wondered if uncouth meant uncouth then what did couth mean, and now I knew: couth meant Edith.” She’s elegant in ways that Ava isn’t, and she’s affectionate like Julian can’t be.

A more compelling reading of the book—and this is not a knock against the love triangle—is that this novel is about the modern workplace. I have never read fiction that so perfectly captures what it’s like to teach children, engage in the sometimes morally dubious task of teaching English as a foreign language, or have a job you hate. For a book about teaching abroad, there is remarkably little description of traveling, experiencing foreign street life, or “finding oneself” on the other side of the world. In fact, Ava’s disdain for those who travel to learn more about themselves is both mean and refreshing. The other teachers at her school often quit at a moment’s notice: “Most were backpackers who left once they’d saved enough to find themselves in Thailand. I had no idea who I was, but doubted the Thais would know either.”

For a book about teaching abroad, there is remarkably little description of traveling, experiencing foreign street life, or “finding oneself” on the other side of the world.

Instead of wide-eyed portrayals of weekend trips away from teaching, Dolan describes the teaching itself. The textbooks at Ava’s school are inadequate; her “greasy and parsimonious” boss won’t let her take breaks between classes to pee. “The buck stopped with him,” Ava thinks, “a reflection of his general distaste for parting with currency.” The children in her classes are mostly sweet, but Ava dislikes categorizing “any usage that might hint a Hongkonger was from Hong Kong” as a mistake. Part of the reason this makes her uncomfortable is because it’s familiar to her as an Irish speaker of English. “If the Irish didn’t aspirate and the English did then they were right, but if we did and the English didn’t then they were still right. The English taught us English to teach us they were right. I was teaching my students the same about white people.”

Many of the sharpest and most memorable passages in the novel are about the differences between standard (British) English, Hong Kong English, and Irish English. These don’t veer toward pedantry, although it’s clear Dolan knows what she’s talking about. Usually, these interludes of comparative grammar relate to the plot:

The twelve-year-olds were on the perfect aspect, God love them. … Past perfect if it: (a) continued up to a time in the past, e.g. “They had been living together,” or: (b) was important in the past, e.g. “I had thought I loved him until I met her.”

This reinforces the book’s overarching structure: Ava’s often unsatisfying love life and always unsatisfying work intertwine in her churning mind. For those readers currently quarantined at home dealing with parallel issues, Dolan’s book is a welcome and unexpected respite.

Chapel Hill, North Carolina