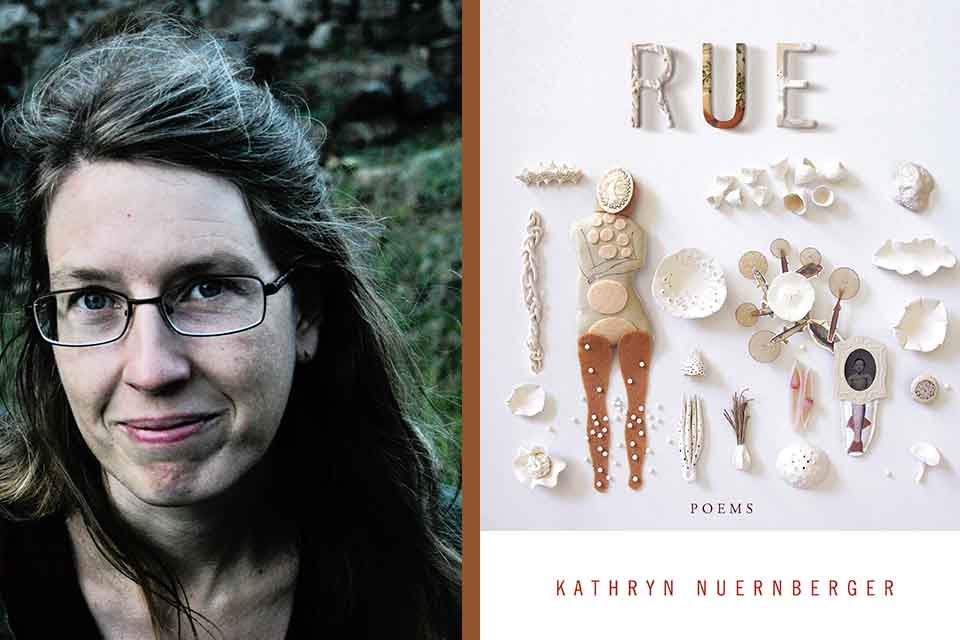

Kathryn Nuernberger is the author of the poetry collections RUE, The End of Pink, and Rag & Bone, and the essay collections Brief Interviews with the Romantic Past and The Witch of Eye (forthcoming in 2021). Her most recent poetry collection, RUE, is an ecofeminist meditation on plants that were historically used as birth control. Throughout RUE, intimate reflections about the speaker’s own life are interwoven with the biographies of women ecologists. Of Nuernberger’s most recent work, poet Erika Meitner has written: “RUE is a brilliant meditation on corporeality, history, and what it means to move through the natural and material world—be it a field of pennyroyal or the Dollar General—in a female body.”

In the following interview, conducted via email, we talked about historical figures in botany and ecology, legendary midwives, deep issues in law enforcement and systemic racism, gestures of solidarity and resistance, and the contracts of genre. Sarabande Books will publish The Witch of Eye next year, Nuernberger’s essay collection that investigates the “witches” of the past, holding transcripts of witch trials up beside Title IX lawsuits and demonstrating how these early documents can be seen as transcripts of resistance and defiance in the face of dominant narratives of coercion and patriarchal control. Throughout both RUE and The Witch of Eye, the speaker deftly moves between history and the present, reflecting on where societies hurt the hardest and offering insightful perspectives on possibilities for healing and transformation. The following is an excerpt from our exchange.

Kathryn Savage: In RUE, poems about plants that were historically used for birth control is the formal framework you use to write about historical figures in botany and ecology and also more personal narratives. Motherhood, marriage, desire, the body, grief, death, patriarchal bullshit, deep knowledge of the natural world each take their turn in your thrilling new collection. RUE feels both deeply personal and also rhetorical and scholarly. It’s a fantastically balanced book. What was it like shaping this collection and arriving at its form?

The poems in their finished forms sometimes exaggerate indignation, fury, yearning, and grief in a way that I think was necessary to translate my experience onto the page.

Kathryn Nuernberger: Early on I didn’t really understand how deeply connected those poems about abortifacients were to my sense of profound alienation living in a rural Missouri town with a very patriarchal culture inside a marriage that had fallen into patriarchal patterns after we became parents (which often happens even among socially progressive partners).

Midway through writing the book, I thought I was writing about my inevitable divorce. But since we weren’t divorced yet, my husband, who has always been my first reader and editor, kept workshopping the poems with me. The line between when we were working on poems and when we were working on our marriage became quite blurry. Some of the poems in RUE are more personal and intimate and angry and accusatory in their final drafts as a result of his very good editing advice. Like a lot of women, I was socialized to repress my anger; like a lot of men, he was socialized to ignore subtle emotional cues in the people around him. The poems in their finished forms sometimes exaggerate indignation, fury, yearning, and grief in a way that I think was necessary to translate my experience onto the page.

Because I’m always revising old work as I write new material, a lot of the poems that appear early in the book were crafted later and reflect my understanding of the confluence of macro- and microcosmic forces that were contributing to my anger. They also reflect an understanding I only came to around the time I was finishing up this book that anger is actually a deeply hopeful emotion. I only thought about a divorce when I could no longer see a point in arguing, when I could no longer see the potential for a change between us. Soraya Chemaly writes beautifully in Rage Becomes Her that anger “begets transformation, manifesting our passions and keeping us interested in the world.”

Savage: Building on the idea of change and transformation, I wonder if you consider poems to be political actions?

Nuernberger: During one of the years I was writing RUE, I was following Emma Sulkowicz’s performance art piece Carry That Weight. She carried the mattress on which she was sexually assaulted around Columbia University campus from September until May. In the beginning that piece was a performance of an unbearable burden, but people began to help Sulkowicz carry the mattress, and in those gestures of solidarity I began to imagine how art can serve as a nexus. One of my poems, “Poor Crow’s Got Too Much Fight to Life,” ends with the lines: “I’m sorry, other people he might have or still yet / hurt, but I’m not so naively idealistic as to think / any good could come of saying to the public that I was / assaulted by an OB/GYN in his office in Logan, OH / in May 2010 and I’m willing to testify to that.”

I wanted this poem to be a rallying cry if there is a rally to be had. And if there’s not, then I think art and confessional poetry has even more of a purpose, holding the truth of whatever experiences we can speak about clearly for some future moment when those testimonies can coalesce into a movement or class-action lawsuit.

Savage: I hear you. Across your work, I was reminded of something Rachel Carson wrote in Silent Spring: “We are accustomed to looking for the gross and immediate effect and to ignore all else. Unless this appears promptly and in such obvious form that it cannot be ignored, we deny the existence of hazard.” I know you have a deep interest in ecology and intersectional feminism. Because your work is concerned with women’s bodies and the natural world across large swaths of time, I feel yours is an important model for resisting the erasure Carson is talking about—the social and judicial pressures that seek out immediate proof. Carson is talking about ecological violence in Silent Spring, but I’m thinking about rape now, and statutes of limitation that can pose barriers to justice. The Witch of Eye includes an essay about a Title IX investigation. In this essay, you write: “Because my point was not Woman, per se, but something about social control and the mythologies of justice systems.” One thing I find so endlessly thrilling in your work is your capacity to swiftly collapse the past and present. Do you think this formal collapse, when writing toward broad time, is a political gesture toward resisting hegemonic and historic erasure? Because your work shows long legacies of systemic violence, do you see yourself working within lineages of poetry and lyric essays of witness?

Nuernberger: A lot of people are only able to achieve a measure of justice against their abusers if they also sign a nondisclosure agreement. A lot of people who prosecute their abusers are immediately sued by them and face insurmountable legal fees if they seek recompense. A lot of abusers are well connected and able to use the criminal justice system to further harass their victims to the point of financial ruin. A lot of people know the moment they are most likely to be killed is when they try to leave an abusive relationship. Some university administrators will tell women, trans, or nonbinary faculty who feel threatened by a male student that they are blowing the situation out of proportion, or they will blame that teacher for the crisis. Some campus security officials will respond to a request for extra security by giving that faculty member a pamphlet for a self-defense class at the student rec center. A lot of social media websites will describe young men posting their fantasies about committing mass shootings as profitable.

I spent five years of my life attending meetings, almost always meetings in rooms with only cis white men present, about the fact that a former student frequently used social media to threaten to kill me, to conduct a mass shooting, posted snuff videos with my name in a post immediately before or after. I had readings canceled because he threatened to attack them in comments on the event page. I got a new job, moved to a new state, scrubbed my address from the internet, kept a file folder on my desktop with over five hundred relevant screen shots, and the entire time I never spoke publicly about this in above a whisper, because I knew the situation could still get much worse.

His death earlier this year means I can tell you in a first-person voice, with clarity and precision, how I have been afraid of my former student and grieved for him and how I blame that institution’s administrators and police officials who ignored my early pleas for help and made choices that made our lives even more precarious. Before, like so many other people I know, I couldn’t risk what would happen if I spoke about this publicly, so I talked instead about what the people on trial in Bamberg or Paisley or Lancashire said hundreds of years ago. Not because I think it creates any justice for what they endured in the past, not because I imagine I can give them a voice, certainly not because I think there is any comparison between my situation and theirs. I talk about them because we can talk with clarity about power and social systems hundreds of years ago and not risk ourselves or our sources being sued for libel or receiving threatening messages in our inboxes. And I imagine that if a critical mass of people can learn from those circumstances something about who gets believed and who doesn’t, the insidious shapes abuse of power and mass complicity took then, well, we might get to walk into a future that looks substantively different from that past.

Savage: I couldn’t agree more. In your essays, I love, and am consistently struck by, the elegant temporal collapse between history and the present that you achieve. At the craft level, what are your strategies for such juxtapositions?

Nuernberger: The way we talk about the past shapes the kinds of futures we are capable of imagining. My first drafts are always focused on a moment in history that inspired me because it suddenly made some new possibility for the future feel possible. But to transmit that sense of insight out of the past into reader’s conception of the present and future, I find it necessary to give them something of my personal and present moment.

I’m really enchanted by the way literature creates a sensation of perfect understanding between a writer and reader, even when the writer is dead and the reader hasn’t been born yet. The shapes my essays take vary widely—I’ve written an essay in a variation on the poetic form of a pantoum, sometimes I braid them, or try to make each paragraph like a link in a crown of sonnets. But in general I’m drawn to forms that embrace wild juxtapositions, because they mirror the wild juxtaposition that is trying to get a sensation from my mind and body into yours.

Savage: I’ve been reading The Witch of Eye beside Sue Grand and Jill Salberg’s Trans-generational Trauma and the Other: Dialogues across History and Difference. Their book takes a psychoanalytic perspective to some of the ways trauma is passed down between generations and asks readers to revisit ghosts. To “creatively cross the boundaries of time and geography to illuminate previously unspoken realms of suffering and injury,” as a move toward restorative justice and more accountable histories. In your work about the “witches” of the past, you write about narratives of trauma, of torture and forced confessions, beside contemporary acts of evil such as police violence against black lives, gender-based violence, and environmental violence. Your wild juxtapositions are skillfully negotiated. How did you arrive at the right formal structure to hold such expansive content?

People often compare witch trials to present-day sexism and misogyny, but I see a more exact parallel in our criminal justice system’s treatment of people of color, most especially black men.

Nuernberger: The historical records themselves often suggested the structure. At first I struggled to understand how the inquisitors could possibly believe the things they accused the witches of. Surely the judges didn’t really think Agnes Waterhouse kept demons in her kitchen pots or let them loose to prowl the neighborhood demanding butter? They couldn’t really believe that Elisabeth Styles let the devil take the form of a butterfly and suck her blood? But it was equally perplexing to imagine that people didn’t believe these things. Because why would people torture and execute others for no reason at all?

To try to understand, I read a lot about the psychology of false accusations, false testimony, and false witness. People often compare witch trials to present-day sexism and misogyny, but I see a more exact parallel in our criminal justice system’s treatment of people of color, most especially black men. As you know, George Floyd was murdered by police in our city this month. And as with Philando Castile and Freddy Gray and Michael Brown, the violence by police is almost incomprehensible. The officers’ defense in these cases is usually that they were afraid of these unarmed people who have committed no crime at all or a minor infraction. I don’t want to waste much breath trying to empathize with cops who kill civilians, but I think it is important to understand that fear, which we also hear about in the accounts of the people, often white women, who call the police on black people in the first place.

It turns out it’s not hard at all to convince people to see the world in a delusional way, especially if they gain power via such delusions. You can convince a village that when they look at an old woman they see a witch just as easily as you can convince a significant percentage of white people that when they look at a black person they see a dangerous criminal.

But in the trial records, as on the streets of Minneapolis, if you’re looking for it, what you can also find are gestures of resistance and defiance. Sometimes the resistance came in the form of the accused refusing to confess, even when prosecutors promised to let them off with a warning if they’d say the words. There was powerful resistance in the hex Agnes Naismith put on every single person who gathered beneath her scaffold to watch her die. In the case of the Brazilian witch Maria Barbosa, she asked Portuguese inquisitors for a blanket when she arrived in their courtroom after a harrowing journey. In that moment she was neither hopeful nor naïve; she was resisting their systemic power by reminding each individual man of the humanity he could exercise if he had the moral courage to do so. The implications of their failure to show her mercy hung over the rest of those proceedings. Such instances of defiance were what interested me the most in the witch trials, and in every essay I looked for structures and details that would amplify those notes.

Savage: George Floyd’s murder by police, in no uncertain terms, is the result of white supremacy in all its overt and covert manifestations. George was a part of my son’s school community. This month, I’ve marched with a heavy heart and mothered with a heavy heart. I’m white, and so is my son. I hope you don’t mind a more personal question. We’ve been talking about writing as resistance. We both write, sometimes, about being mothers. I wonder how you parent toward resistance?

Nuernberger: I’m so sorry for the terrible loss to yours and your son’s school community. George Floyd was such an important part of so many people’s lives, and it is unacceptable that his murder should go unpunished or that our criminal justice system should be allowed to continue on with business as usual. One of the terrible parts of parenting is having to tell our children the world is not very safe and not very just. I wish I had been at this protest with you—when I spoke with my daughter about George Floyd’s death, I pointed, as I so often do, to the courage and resolve of protesters in the streets demanding arrests and reforms. Mr. Rogers always said that in times of despair you should look for the helpers (or, if you are an adult, be them); I’ve modified that beautiful sentiment slightly to say, Look for (or become) the activists.

To answer your question more precisely, though: I listen for advice from parents who are people of color about what they wish white children knew. The Center for Racial Justice in Education has a list of “Resources for Talking about Race, Racism and Racialized Violence with Kids” that I refer to often. The We Need Diverse Books organization has created one of my go-to websites as a parent trying to figure out how to raise a white person who will be prepared to help dismantle oppressions. I also refer to the Zinn Education Project for materials to supplement her education, or in some cases to counteract the white-supremacist, settler-colonialist propaganda that permeates a lot of elementary textbooks and classrooms.

Since a nine-year-old is always underfoot, especially during this year of pandemic homeschooling, I invite her to participate in my research processes for works-in-progress, which necessarily includes working to decolonize my own thinking and interrogating my privileges and implicit biases. For example, our bedtime reading of late has come from Mary Siisip Geniusz’s Plants Have So Much to Give Us, All We Have to Do Is Ask, which is a book of Anishinaabe botanical teachings informing my new writing project. We’ve also been cooking together from Heid E. Erdrich’s Original Local, a collection of indigenous recipes, stories, and reflections on food from the Upper Midwest.

I also include her in my activism whenever it is safe or appropriate to do that. She’s done a lot of marching over the years and will tell anyone who asks in her most complainy voice just how boring city council meetings can be.

Savage: I’ve been so steeled by the courage and resolve of the millions of protesters, globally, taking to the streets and raising their voices, sending a clear message that racism and racist violence must end. I agree that showing children activism, and reading together, are (among many) necessary steps to counter racist socialization and implicit bias and to initiate critical conversations at home—empowering youth to see themselves as participants in a move toward racial justice. More importantly, listening from parents who are people of color about what they wish white children knew is critical. Returning to your writing, how did you go about researching witch trials? Were there certain texts or archives that were particularly instrumental in informing your work?

Nuernberger: When I was writing the poems about plants used for birth control, I couldn’t always find out what part of the plants was used, when it was harvested, what dosages were used. And, as you know, a poem relies on detailed imagery. Then I remembered hearing that many accused witches had been midwives, and I wondered if they might have spoken about their recipes in the course of their trials.

I landed on a Wikipedia list of a couple hundred people who had been executed for witchcraft and gave myself the project of clicking on one name each morning and writing a little meditation on that person in my notebook. Wikipedia articles often have generous endnotes, and it was those that led me to the incredible archival, documentary, and analytical work of serious historians. Some of them, like Emma Wilby’s Visions of Isobel Gowdie, included appendixes that reprinted all of the transcripts and other documents from the trials. Transcripts from the proceedings in Salem are widely available online. Laura de Mello e Souza’s The Devil and the Land of the Holy Cross draws extensively and in great detail from the available records of the Brazilian witch trials. Once I had started reading these works, well, endnote leads unto way leads unto one book after another in this massive field of thorough scholarship and primary sources.

Savage: In instances when you were working with problematic sources, how did you add cultural commentary to the archives—talk back to the stacks?

You could write a long bibliography of the historians who have believed women were exaggerating about the trials, or that the accused were just crazy, or who thought it very important to constantly turn the subject back around to “hey, some men got tried for witchcraft too.” Thank goodness for feminist historians like Silvia Federici who have done a lot of work to help us see how the witch trials laid the groundwork for a great many injustices that are with us today.

But also a lot of the scholarly writing about Tituba of Salem, Marie Laveau, and other accused witches who were people of color is laced with racist assumptions and ignorance. White historians often struggle to fully appreciate the ways rhetoric of resistance and gestures of defiance can or must be wielded differently by people of color. Too often I see my own limitations of understanding, my own ignorance, my own implicit bias reflected in a historian’s account of an accused witch’s circumstances. When I found myself talking back to the stacks, I was really talking in frustration with myself and the ways privilege and white fragility sometimes keep me stupider than I want to be.

Savage: As a multigenre writer, at what stage in your writing process can you tell if a work is taking the shape of a poem or an essay?

Nuernberger: Genre is most interesting to me when I think of it as a contract between myself as the author and the reader who is picking up my work. If I offer them a poem, the contract between us is that they will encounter elliptical thinking, associative logic, leaps, fragments, and unlikely juxtapositions. If they are picking up an essay they are expecting to be educated through a coherent narrative with a certain amount of connective tissue that explains the movement between one idea and the next.

Because I’m surly and often feel my purposes are best served by disorienting my readers before I reorient them, I often present my most coherent narratives as poems, and choose the essay form for my wild leapings.

Genre is most interesting to me when I think of it as a contract between myself as the author and the reader who is picking up my work.

Savage: As a professor of creative writing at the University of Minnesota, you’re no stranger to nudging other writers’ nascent ideas (wild leapings?) along. In a recent craft essay, you offered the sage advice to poets and essayists to look for the “vestigial tails” in one’s work, which you define as the “pieces that seem odd or distinct from the other works in the book where they first appeared, but fit in nicely with a book that came after.” I wonder, in writing RUE and The Witch of Eye, if they were ever one book? What were the “vestigial tails” in your most recent body of work? Did you write them simultaneously, or did one book come first?

Nuernberger: These two books are very much sister projects. Not only did research on ethnobotany for RUE lead me to reading about witch trials, but the galvanizing defiance I found in those accused witches’ voices was also the most important medicine I was finding in the abortifacients too.

Savage: What are you working on next?

Nuernberger: I think I’m writing a series of prose poems (or maybe they are flash essays?) about instances of symbiotic mutualism in the natural world. I’m very interested in the ways certain species evolve to live together in mutually beneficial ways. Like cocktail ants burrow into acacia thorn trees, creating galls which could destroy the tree, but the tree feeds them nectar through those galls and communicates other messages with pheromones. The tree can then ask the ants to attack any herbivores that come to graze, increasing both species’ chances of survival. Goldenrods allow certain flies to lay their eggs in galls on its stems, at some cost to the plant, because the larvae feed on a pesky bacteria and they also return as mature flies to pollinate the flowers. Bobtail squid rely on bioluminescent bacteria that colonize a cavity behind their eyes in order to camouflage themselves with moonlight on the waves.

I suspect it is unreasonably hopeful of me, but I like to imagine humans could be in a different relationship to our ecosystem if we better understood how symbiosis and mutual aid are the biosphere’s default modes of operation.

June 2020