Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

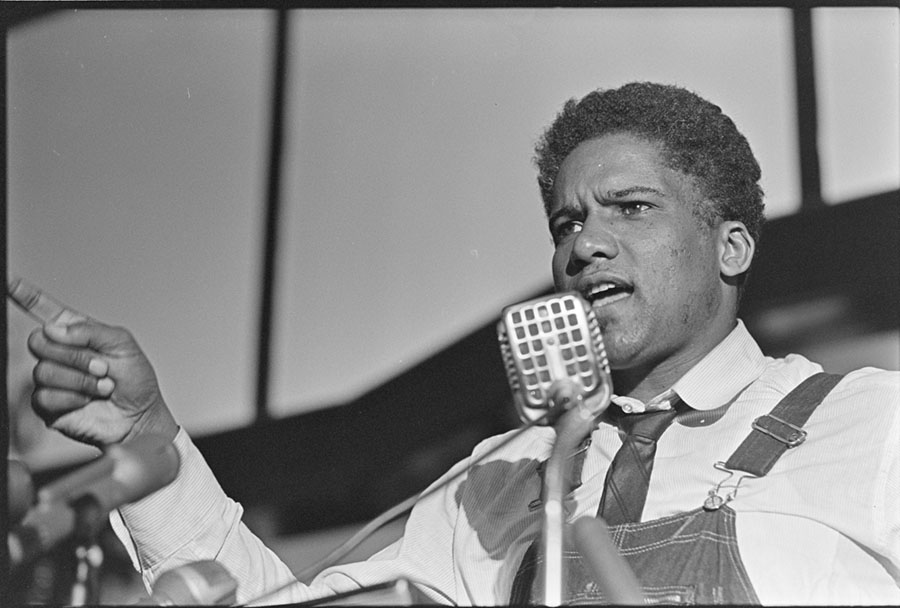

One Sunday in the spring of 1969, James Forman walked into the sanctuary of Riverside Church in the Morningside Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, barreled his way to the pulpit, commandeered the microphone, and before many wide-eyed and captive congregants, declared:

Underneath all of this exploitation, the racism of this country has produced a psychological effect upon us that we are beginning to shake off. We are no longer afraid to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.

Forman chose Riverside Church for the delivery of his address—The Black Manifesto—because of Riverside’s association with the Rockefeller family and for its Morningside Heights location. In his view, the church embodied both types of white American capitalist oppression: generational wealth, in the form of the Rockefellers, and elitist white enclaves within the city.

Columbia University’s transparency project focusing on its ties to American chattel slavery says of Morningside Heights: “[The university’s] move to its current campus at the turn of the 20th Century served to preserve the area’s elite, white, Episcopalian character and keep out people of other ethno-racial or religious backgrounds.”

That morning in his address at the Riverside Church, Forman accused all white Christian churches and synagogues “sustained by the military might of the colonizers” of complicity in establishing and maintaining America’s racist constructs. He demanded $500 million, about $3.6 billion today, “due us as people who have been exploited and degraded, brutalized, killed and persecuted.”

We can imagine the churchgoers in sticker shock, their nervousness and fearful clutching of purses.

In a Sunday service like no other, Forman called for $200 million in land grants, $10 million for technical training, $20 million for black businesses in America and Africa, and funding for a black university in the South. He had counted the cost of America’s comfort, but he made clear “…the demands we make are small.”

He said “an indigenous people violently captured, taken from home, and bound to political servitude “by the military machinery and the Christian church working hand in hand … can legitimately demand this from the church power structure…” and even more from the U.S. government. We can imagine the churchgoers in sticker shock, their nervousness and fearful clutching of purses—their urge to stand up and stomp out of the sanctuary, their sheer terror at the idea of making a move, their outrage as he went on, banging through threats and demands.

But The Black Manifesto was about more than money. It also required certain action from white people. A certain posture, too:

We call upon all white Christians and Jews to practice patience, tolerance, understanding, and nonviolence as they have encouraged, advised, and demanded that we as black people should do throughout our entire enforced slavery in the United States. … By taking such actions, white Americans will demonstrate concretely that they are willing to fight the white skin privilege and the white supremacy and racism which has forced us as black people to make these demands.

Forman, a Chicagoan by birth, had always been an impassioned intellectual. He lived with his grandmother in Mississippi as a child. Excelling in school, he matriculated to universities in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, and New York, but along the way, he suffered a brutal and traumatic encounter with police that would see him institutionalized, shaping his remaining years and his life’s work. Of that time, he wrote in his autobiography The Making of Black Revolutionaries: “I will always remember the Los Angeles police […] They are guilty of cruel and inhuman treatment, physical and mental torture.”

As a staff writer for the Chicago Defender, one of the most important black news publications of the day, Forman developed a burgeoning consciousness that fueled an urgency to achieve black civil rights.

In his executive leadership role at the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, his aim was to “[work] full-time against the whole value system of this country,” wrote Julian Bond, who co-founded the organization in 1960. Forman’s platform was enlarged and elevated through that commitment, and it was largely by his influence, Bond said, that SNCC had a significant role in the 1963 March on Washington. Forman helped draft the speech delivered at the march by SNCC’s then-chairman, the recently departed Congressman John Lewis. Through his involvement with other black advocacy groups, including the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Black Panther Party, Forman was further validated in circles of black civil rights activists and advocates.

But he trained and led black youth in a radical style of protest actions, sometimes denigrating King’s approach as something near toothless by comparison. “People had become too militant for the government’s liking and Dr. King’s image,” he wrote. “The mighty leader had proven to have feet of clay.”

Forman had run out patience with the way things were. He was full of fire.

To the dismay of affiliated organizations, Forman garnered respect for strong-arm ideas that would become his hallmark. “Accumulating experiences with Southern ‘law and order,’” he wrote, “were turning me into a full-fledged revolutionary.”

Following the assassinations of Medgar Evers and Malcolm X, and then Martin Luther King, Jr., who had preached at Riverside on several occasions throughout the ‘60s and with whom Forman had marched, there was a sense among blacks in America that the movement for black civil rights had died with those leaders.

Later that summer, following the Riverside Church takeover, Murray Kempton wrote a piece about the Manifesto for The New York Review of Books, in which he gave voice to a painful truth about the crusade and the crusaders for black civil rights. “The existence of the black revolutionary, of course, is only too often the business of making do between the time he is noticed and the time he is shot,” Kempton wrote.

In spite of this, Forman felt, the time for accommodating open hatred with careful, unoffending words, all to realize no meaningful change—that time was over. He was a student of philosophers and revolutionary theorists like Karl Marx, Frantz Fanon, and others whose writings expound on the interdependence of race and class as a tool of the State. “There can be no separation of the problems of racism from the powers of our economic, political, and cultural degradation,” he wrote. “For it is the power of the United States Government, this racist, imperialistic government, that is choking the life of all people around the world.”

Forman had run out patience with the way things were. He was full of fire and, under a political charge to equip and lead black people through the racial terrorism of the American landscape, he wrote The Black Manifesto.

Forman’s address brought a response from the Episcopal Church, with promises of actions and some funding, but not without cost. Ironically, his comportment in white society stoked fears and dissent among some in black communities.

“Forman’s … function is kicking down doors to empty rooms,” Murray wrote. A curiously reductive assessment when considering Forman’s life of leadership in black civil rights, the self-actualization and empowerment stirred in us through his work; and the timeless philosophical and socioeconomic applications of the Manifesto.

Forman wrote the Manifesto while attending the National Black Economic Development Conference at Wayne State University in Detroit, the month before his address. Detroit is significant as the birthplace of the Manifesto. It was one of the last stops along the Underground Railroad for slaves crossing the Detroit River into Canada. In the antebellum, members of The Order of Emancipation, which included some whites, helped to make the town a hub of abolition.

Then as now, the Manifesto spoke to a social contract that had long been trampled underfoot.

Then as now, the Manifesto spoke to a social contract that had long been trampled underfoot. It challenged systems and constructs designed to make black progress unlikely, to harm black people, and worse. It examined white allyship and looked for evidence of those things white people say they believe about establishing, upholding, protecting, and meeting standards of conduct in the world, and its resources that we all share. “We shall liberate all the people in the United States…” reads the introduction. “All the parties on the left who consider themselves revolutionary will say that blacks are the Vanguard.”

Ironically, it’s by the unchanged nature, incomprehensible greed, and barbarism of whiteness that Forman’s Manifesto remains critically applicable to black life in America, and has even become anthemic. Fundamentally, The Black Manifesto is about democratic socialism. It’s about leading with those principles that are heartfelt, even inherent, to most of us. Boiled down, it’s a promise of accountability to one another, and accountability is retributive, restorative, and reparative.

Today, in one of the most arresting moments of our time, in the pretense of a flat society where white people “don’t see color,” where “we’re better than this,” where “we’re all in this together,” James Forman’s vision cast so long ago still suffers bullets and billy clubs and knees to the neck. Today, every Black person you know is buckling under the crippling weight of yet another hashtag. Today, the unmet demands of The Black Manifesto echo in that mocking, deafening silence of so many yesterdays, and it still reads shamefully fresh.

Forman demanded $10 million to establish a black publishing and printing industry, “an alternative to the white-dominated and controlled printing field.” More than half a century later, American media continues to prove incredibly resistant to black representation. Just last year, The New York Times, widely considered the gold standard in American journalism, showed a blinding 76% white leadership compared to just 6% black, and only 9% of the staff was black according to its inaptly-named Diversity and Inclusion Report.

The Manifesto is symbolic of America’s accruing and compounding indebtedness to black people.

And in his call for $20 million “to establish a National Black Labor Strike and Defense Fund … for the protection of black workers and their families who are fighting racist working conditions in this country,” Forman speaks directly to today’s capitalistic scheme targeting the mostly black and brown, often blue collar, under-insured, and low-wage earning “essential worker.”

The Manifesto is symbolic of America’s accruing and compounding indebtedness to black people, a stolen people, who built the nation and its economy through generations of labor, whose blood is in the soil.

While Forman’s techniques weren’t wholly adopted or even appreciated by the NAACP and other black advocacy organizations, his approach to reparations for African chattel slavery and its many resulting devastations were appropriate for that time and for this one. James Forman, a leader and a comrade in the fight for black humanity, succumbed to cancer in 2005 at the age of 76. But the Manifesto is as vital a roadmap in our marches and protests today as the day it was first delivered. We, black people in America, remain compelled by the power and purpose of The Black Manifesto, and we continue to demand our full rights as a people of this decadent society.