Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

In recent months, we’ve been overwhelmed with suggestions to read James Baldwin, Ibram X. Kendi, Audre Lorde. But it may be even more illuminating to read more obscure Black authors, who are equally unabashed in their writing but never achieved mainstream acceptance and success. Many of them remain obscure specifically because they opted to write without making the white gaze their primary motivation in writing those unadulterated stories, and that kind of candid storytelling is what all readers, white and Black, need right now.

One of these authors is Robert Deane Pharr, who chose to write about Black people’s lives in an unfiltered manner, claiming “[only] I would let white people look at the Black man as he lives when the white man is not looking or listening.” With this aim, he’d create worlds with a writing style that was as colorful as it was prescient. And with the recent spark of global protests over systemic racism, set off when police killed George Floyd, Pharr’s writing should have some place in critical discussions of those issues.

This kind of candid storytelling is what all readers, white and Black, need right now.

I discovered Pharr’s writing in high school while working as a page at the Queens Public Library. Being in this job fed my voracious appetite for reading, especially for anything related to Black culture and history beyond the bland texts assigned to me. S.R.O. stood out to me visually first, before I had an idea of its contents: the cover, a desaturated city building with the title in bright red letters, gave it a noirish air. The blurb on the back was the kicker, speaking of Harlem in the 1960’s, which was when my late father used to live there. The novel was part of the “Old School Books” series by Norton featuring Black novelists from the 1960’s and 1970’s. I devoured all 544 pages and to this day, that book remains among my favorites to read.

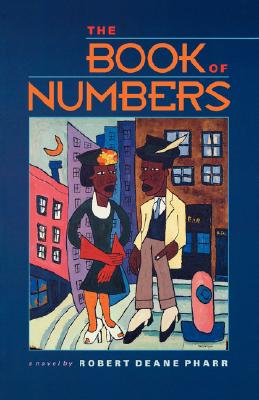

Pharr’s literary voice centered Black voices, mainly people from the margins of American society, depicting their lives in an unvarnished manner with cynicism and hope. No respectability politics for him. In his few available published interviews, Pharr cites being inspired by the writing approach of Sinclair Lewis, who was known for his poring observational tone. This approach was the basis for his first and most successful novel, The Book of Numbers, published in 1969. Pharr’s candid look at two men who create a numbers racket in the Black community of Richmond, Virginia in the 1930s garnered attention for its look at two waiters, Blueboy Harris and Dave Greene, who briefly achieve success before seeing it all end in tragedy. S.R.O., about a waiter’s life in a single room occupancy hotel in Harlem, and dark comedy Giveadamn Brown followed right after. Each of these novels drew heavily from Pharr’s own life experiences and observations as a longtime waiter after he graduated from Virginia Union in 1937—he was 53 as he was on the job at the Columbia University Faculty Club when he arranged for a professor to read his manuscript.

Pharr’s depiction of policing as an unreformable system built to brutalize and oppress Black bodies and others of color in his work rang true then and truer today. In The Book of Numbers, Blueboy dies in an agonizing way after cops beat him so badly they rupture his intestines. In Giveadamn Brown, the intimidating crime lord Harry Brown is called in to try to rescue a dealer from an abandoned building who’s kidnapped three white NYPD officers for stealing fifteen kilos of drugs from him. This exchange between NYPD senior official and Harry is telling:

“For God’s sake, Harry!! We can’t have no execution of three cops on TV. What the hell you think this is anyhow?”

“I think it’s a damned good show.”

The dealer winds up dying with the officers when the rest of the police on the scene set off an explosion rather than have their misdeeds made public. The police don’t fare any better in S.R.O., where the protagonist Sid Bailey is being questioned as if he’s a criminal by one of two cops called to prevent a woman from stabbing him to death. After the incident, Sid develops a violent hatred of cops. He goes into a psychiatric ward after a nervous breakdown over the near stabbing, gaining insight on that hatred as well as his alcoholism. Reading this novel again, I find a striking connection in how Sid relates his treatment by the NYPD to the therapists and those conversations I’ve had with friends and relatives online and offline. Our conversations are as tinged with anger and resignation as Pharr’s dialogue was over 40 years ago.

Police brutality against Black people isn’t the only issue where Pharr prefigured our current concerns. He wrote of gentrification as a looming, leering colossus waiting to take Black people’s homes for the aims of white business and pleasure. This is playing out in cities across America at an alarming rate today, yet in Giveadamn Brown and S.R.O. of the ‘60s, Pharr already depicts Columbia University is that villainous colossus—an idea that still has validity as the school expands through West Harlem. This is expressed in a tirade in S.R.O. from Sid’s close friend, Blind Charlie:

Here I am, taking you for the first time to show you where a bastid what’s on Welfare should go to buy his daily bread, and you got the nerve to tell me what Columbia don’t own? Columbia owns every inch of ground you walks on every day. And don’t tell me it don’t! You aint been more’n five, ten blocks away from the Logan in months. And Columbia owns all this land for twenty blocks in any direction!

Pharr also anticipated the growing awareness that Black women, in particular, have been overlooked and undervalued. His Black women characters and other women of color are multifaceted personalities who have been forced to be the bedrocks of communities where the men have been decimated or torn down by hustling, war, alcoholism and prison. Though Pharr doesn’t avoid some outdated tropes, his female characters are more than mere foils. There’s Gloria Bascomb, Sid’s lover from S.R.O. who’s a former heroin addict and call girl who embraces Sid with a love that supports him through alcoholism and schools him on “the life,” but not without taking him to task for being cynical about Black liberation. There’s Margo Hilliard, the “Foxy Cool Momma” who is Giveadamn Brown’s first lover and hips him to the ways of the streets. Pharr also depicts women who love other women in a range of ways that show deep consideration, seen prominently through S.R.O.’s Joey and Jinny, a lesbian couple composed of an former Irish hijacker and a Black con woman who also become part of Sid’s “family” in the Logan. In Giveadamn Brown Pharr even has an asexual character, Connie Hawkins, which puts him ahead of most modern literature in terms of representing the full range of women’s desires.

Critics loved Pharr’s work, raving about his raw look at Black life. But some felt he was too raw.

Critics loved Pharr’s work, raving about his raw look at Black life in America. This critical acclaim for his viewpoint led to a film adaptation of The Book of Numbers, part of the wave of Blaxploitation movies. But some felt he was too raw, and wanted to focus on writers who offered a more positive outlook on race relations in the U.S. This downturn would soon put him back into obscurity, fueled by his frustration with the publishing industry and his own battles with alcoholism. Pharr would go on to write two more novels—The Soul Murder Case and The Welfare Bitch, both so obscure that copies are a rarity. Pharr would live the rest of his days in upstate New York, passing away in 1989. But Robert Deane Pharr left American literature with some important lessons to be learned concerning Black people of all walks of life—lessons that deserve a second look amidst protesters’ calls for society to confront its dependence on systemic racism. The very things that keep Pharr obscure—his unwillingness to pander to white readers, his focus on writing about Black life at all levels of American society in a plain-spoken way, his anger at the way Black people have been abused and murdered in different ways by this society—are the reasons we need him right now.