Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

In order to fit more texts into my Asian American literature course, I sometimes assign the play adaptation of Jessica Hagedorn’s novel Dogeaters. The novel is canonized within Asian American literature and features an imagined version of the Philippines made from film and radio tropes, found texts, political discourse, talk shows, rumor, gossip, and multiple perspectives. The truth is constructed—this is the point. Likewise, the play opens with a radio broadcast and a talk show (titled “Dat’s Entertainment!”) in which the hosts interview the dead white author of a nineteenth-century travelogue, The Philippines, that hugely influenced the image of the islands in the West.

In the play adaption, the concern with where a story comes from and who tells it comes across powerfully in a scene in which two characters sit on a sofa and watch the audience. The soundtrack indicates that the characters are watching an erotic film—but the film does not exist. Instead, the audience becomes the screen for eros. An image is as much, or more, about who is doing the looking as it is about what is being looked at.

In a way, this essay is a response to a question my daughter posed during a recent Facetime with my mother. My mother (who is white and adopted me from Korea when I was two) was reading aloud a novel, about a half white, half Asian girl, which was set around the end of the 19th century. I had filled in some missing context: that Chinese Americans call this period the “Driving Out,” because in the years leading up to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, white people lynched, scalped, and burned Chinese Americans alive, destroying their property and branding their bodies, in attempts to drive them out of the country. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the official government response, in effect condoning white terror.

In the novel, a white father moves his half-Asian daughter out of L.A.’s Chinatown to start a clothing shop for white people. Despite this premise, I felt hopeful about an Asian American girl protagonist. I have been taught to take what I can get. Five minutes in, however, my nine-year-old had already asked my mother to say “Native American” instead of the terms the book uses; I also wanted to strike “Chinamen” and other slurs. “That’s just how people talked then,” my mother said, a familiar argument. Racist terms are too often used to denote historical accuracy, even when the rest of a text remains contemporary.

My daughter wasn’t having it. “So what?” she talked back. “Can’t you say Native American?”

So what?

I had never heard it put so simply.

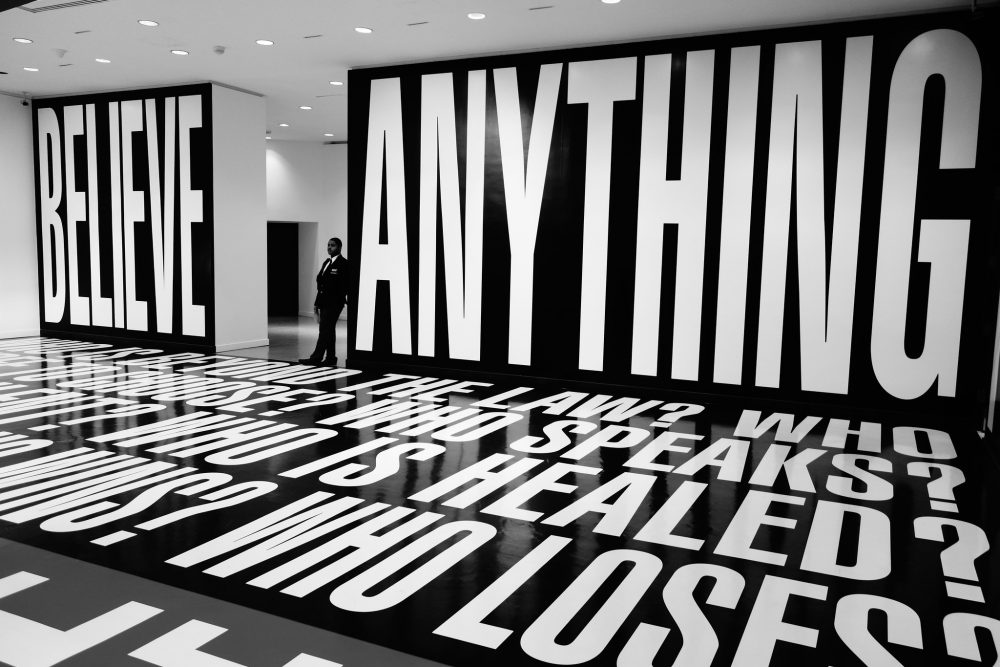

Postmodernism is dead, the critics tell us, but an ongoing concern with the constructedness of culture is alive in every protest. To fight injustice is always to fight a certain idea of the world. An idea has the power to change reality. The sticking point is: Whose idea? And whose reality?

An idea has the power to change reality. The sticking point is: Whose idea? And whose reality?

Fiction began as rumor, as gossip, as counterculture, as tales told by regular citizens rather than by scholars in the capitol. In the West, fiction that refers to its own artifice—for example, an author appearing as a character in his novel—has come to be associated with postmodernism. But this move is much older. Scholar Ming Dong Gu writes in Chinese Theories of Fiction that in Chinese tradition, the “author, narrator, commentator, and reader may all appear [as characters] in the same fictional work.” Gu traces Chinese fiction to its early roots as stories that resisted “official” historical records. It makes sense, in that context, for fiction to emphasize who tells a story and even who listens to a story as important aspects of what the story is.

My American students often read Dogeaters as if Hagedorn’s Philippines is completely other from their experience, while at the same time investing the book with their own very American concerns. (Most recently: a corrupt presidency, racism, sexism, and gender fluidity.) I am reminded of Viet Thanh Nguyen’s comment in Race and Resistance that an Asian setting, versus an American one, may make it easier for fiction to critique American culture, since it can be interpreted (or excused) as a critique of Asia.

Readers sometimes forget that setting is always the work of the imagination—the author’s imagination, and also the audience’s.

Readers sometimes forget to remember that setting is always the work of the imagination—and more than one imagination at that. The author’s imagination, and also the audience’s.

The scene in Dogeaters in which the characters watch the eroticized audience is a reminder that the watching matters. The actors catch the audience in the act of looking. It’s like when you observe someone from across the room and they suddenly catch your eye: your gaze is the gaze you become most aware of.

The Good Story is a book-length conversation between novelist J.M. Coetzee and psychoanalyst Arabella Kurtz, in which they discuss the similarities and differences between fiction and therapy. For much of the conversation, Coetzee keeps insisting that psychoanalysis is truthless and simply replaces a worse fiction about the self with a better one. It’s all a construct, he complains; what about the truth?

Surprisingly, Kurtz has to be the one to defend stories. She pushes Coetzee to consider that the context is construction, that selfhood is constructed and that it would be a mistake to think of stories as a search for absolute, irreducible truth. The therapist does not stand apart from her client and judge what is real and not real about her client’s story. The therapist is part of and takes part in the construction—Kurtz describes how she “comes to adopt the curious position of being both inside [her] patient’s story and commenting upon it as it unfolds.” To intervene, the therapist doesn’t simply show the client that she is making up a story, but must help the client realize whom she is telling the story to.

That is, the client is telling the story not to her therapist but to herself.

It doesn’t surprise me if psychoanalysis has become more useful to contemporary fiction than postmodernism. It’s an Alanis Morissette kind of irony, at best, that a discourse intended to describe a world in which discourse has failed us has itself failed us. Talk may be cheap, but it sure buys a lot. A reality TV star for president may be a postmodernist punchline, but it is also a reality postmodernism never prepared us to confront.

We have accepted that artifice is a fact of life. There is no longer anything more unreal than reality.

The trouble with irony is that our troubles are serious. As are our attempts to meet them. Perhaps this is why we want art to help us replace a worse fiction with a better fiction, rather than to point out its own artifice. We have accepted that artifice is a fact of life. There is no longer anything more unreal than reality.

When our critics fail us, it is often because they insist that art can replace not only other art but reality itself. Before Adam Johnson’s The Orphan Master’s Son won the Pulitzer in 2013, a Washington Post review announced: “Johnson has taken the papier-mâché creation that is North Korea and turned it into a real and riveting place that readers will find unforgettable.” The lack of irony in this sentence is, if not ironic itself, at least appalling. Author Catherine Chung puts it this way in The Rumpus: “North Korea, a nation, an actual nation with real people, is the papier-mâché creation in this review, and the novel, a work of fiction, is the real and riveting place. This is a breathtaking reversal.” (Chung’s italics.)

The characters in The Orphan Master’s Son are unrecognizable as Korean. Chung is able to make sense of the novel only by seeing it for what it really is: a Western about essentially American characters with essentially American concerns.

It is nothing new for American critics to herald white writers who rewrite Asia for white people. In 1954, in an eerie echo, Newsweek called James Michener the man “who makes Asia real to us.” In 1938, Pearl S. Buck won the Nobel Prize for her racist depictions of Chinese. In certain stories, ones written by certain people, transference seems to be just as good as realism. But when we put fictional characters in the role of our therapists, how are they supposed to help us?

Transference (the phenomenon by which the client projects her story onto the therapist) is what marks the brilliance of the Dogeaters scene. What Hagedorn realizes is how easy it is for the audience to forget that it has a role in the story, to forget that it has power. America teaches us to believe that the act of watching is a non-act, that observation is neutral, that we are innocent of the images we see.

America teaches us to believe that the act of watching is a non-act, that observation is neutral, that we are innocent of the images we see.

The play stages a necessary intervention. For one scene, the audience is forced to watch itself being watched. In order to identify itself, to understand itself in the context of looking, the audience must see itself through the eros of the characters.

This is the kind of breathtaking reversal I can get behind. It is a reversal that asks the audience to take responsibility for looking.

One question a writer might ask himself about his craft is: how does the story intervene in its own telling? I had this question in mind as I wrote my latest novel, about a Korean American man who believes he is disappearing. Disappearance is often a matter of why and how we look. Certain kinds of appearance are really disappearances—tokenism, for example, or stereotyping. The Asian sidekick, the Asian gangster, the Asian doctor. When a stranger identifies me as a suspect for “kung flu,” do they even see me? And, if what they see is only a figment of their own imagination, where has the rest of me gone?

This is what the narrator of my novel wants to know. How do you get out of someone else’s story? Especially once you start telling the story to yourself.

One of the most interesting things about protest, to me, are the signs. Protest and its signs understand that to change something, you have to change how people look at it. “Respect existence or expect resistance” is a favorite of mine. “Love is collective, not corrective.” “This is not a moment, it’s a movement.” “If you were peaceful, we wouldn’t have to protest.” “Ally is a verb.”

When the president of the United States calls COVID-19 the “China virus,” he is telling his followers that the virus has nothing to do with them. My father asked me years ago if I was anti-life—I told him, of course, that I was pro-choice. A single term changes the story; it changes who the story is for.

A single term changes the story; it changes who the story is for.

A character who looks back, or a therapist, or a pun or the question “so what?” can sometimes get the audience to notice what it is noticing. Postmodernism might approve. From there, however, the next step is to tell a better story. It is not: no story is real.

Dogeaters presents an artifice dependent on the stories we tell about it. It’s a text made up of other texts: from radio melodramas to the entertainment business to crooked politics. But it isn’t interested in calling certain stories empty or fake. Sometimes a story may fool us, but we would be fools to stop listening to and telling stories as a result. To stop participating in story is to accept a disappearance as an appearance. In other words, talk isn’t cheap after all—saying “talk is cheap” is cheap. It’s a way of shutting down stories with more at stake in the discourse. The discourse can change the reality it describes. It can ask its audience to look better, to recognize its role in making and maintaining culture. In order to see more clearly, we have to change how and for whom we look.