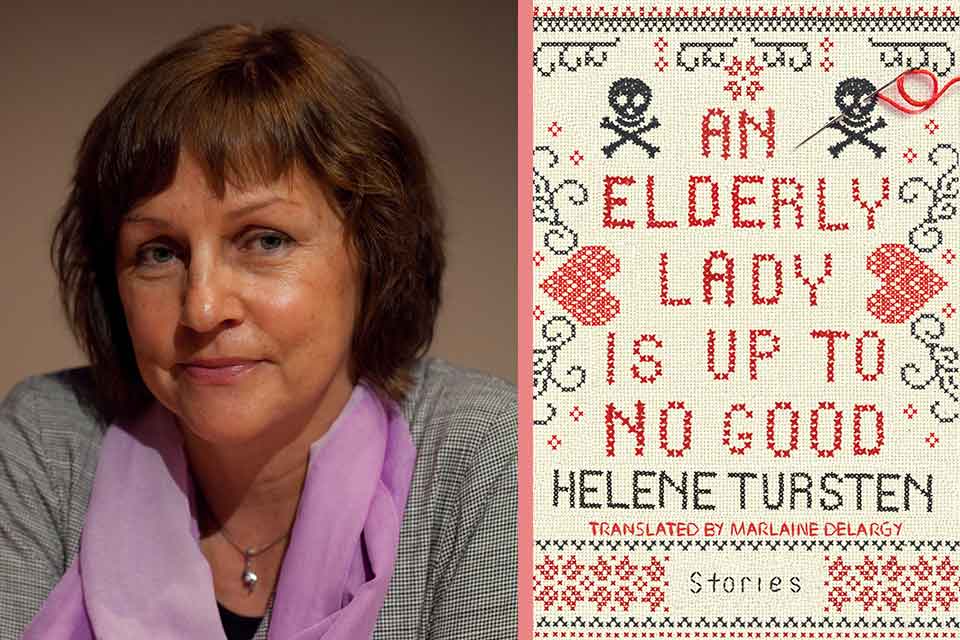

Helene Tursten

An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good

Soho Crime

Trans. Marlaine Delargy

I first picked up Swedish writer Helene Tursten’s collection of stories for its title and for its length; I was intrigued by the promise of scandalous whimsy and comforted by the accessibility of the short, pocket-sized book. Soon, I found that I couldn’t put the book down because of its simultaneous candor and sweetness, which Tursten imbued into the five-part narrative. Each story works as a stand-alone narrative detailing one of the protagonist’s murderous capers.

Yes, murderous. Each homicide is absolutely delightful.

Tursten tells the tale of Maud, an old woman who just wants to be left alone, whose desire to attain such solitude and silence soon becomes twirled with murderous caprice. Maud’s misadventures claim the lives of various nefarious characters, and though I felt that I should decry Maud’s frequent homicides—on the grounds that, well, murder is murder and murder is bad—I could not help but find Maud’s actions more than permissible and her character a verifiable hero. Despite her initial casting as an archetypal crotchety old lady who desires nothing more than her own brand of loneliness, Maud, through her homicidal escapades, strains for the elusive human connection that she at once decries and grasps at as though it were a shadow.

Though I felt that I should decry Maud’s frequent homicides—on the grounds that, well, murder is murder and murder is bad—I could not help but find Maud’s actions more than permissible and her character a verifiable hero.

In the first story, “An Elderly Lady Has Accommodation Problems,” Maud encounters her neighbor Jasmin, a pseudofamous wannabe artist who crafts giant phalluses and tries, through aggressive politeness, to force Maud from her apartment—the only home Maud has ever known. Jasmin’s advances provide the perfect stage for Tursten to implicate Maud’s intense and protracted isolation as the catalyst for the creeping, crushing loneliness, which has snuck into Maud’s solitary life unbidden before it could be unwelcome. “Nobody had hugged her for several decades. In fact, she couldn’t even remember the last time somebody had touched her, apart from the therapists at the Selma Spa Hotel, of course. But that had been entirely professional, rather than an expression of affection.” Maud responds to Jasmin’s false intimacy (and her very real privileged petulance) with what I soon discovered to be Maud’s usual method of dispatching problematic people—murder—and, in this case, a deliciously ironic and side-splittingly hilarious method of eliminating her apartment competition.

This is the magic and the brilliance of Tursten’s collection: Maud kills, and kills often, and kills mercilessly; in spite of that which should be morally unconscionable, Maud captivated my attention and captured my allegiance. In my mind, the old lady could do no wrong. The questions the book asks as it progresses position that very mind-set in conflict with traditional morality: Can we condemn Maud for her murderous behavior? Should we?

This is the magic and the brilliance of Tursten’s collection: Maud kills, and kills often, and kills mercilessly.

The second and third stories, “An Elderly Lady on Her Travels” and “An Elderly Lady Seeks Peace at Christmastime,” continue a trend that began in the opening story: Maud weaponizes society’s ageism to get away with murder. Literally. In “An Elderly Lady on Her Travels,” Maud runs into her ex-fiancé, Gustaf, who has recently become engaged to one of Maud’s ex-students, Siv—now known as Zazza. Maud is suspicious of this engagement, and when she hears of Zazza’s plan to take advantage of the man forty-five years her senior, Maud takes, well, decisive action. In “An Elderly Lady Seeks Peace at Christmastime,” Maud encounters The Problem: an abusive husband serially beats his wife in the apartment above Maud’s. Maud cannot stand the noise—or the man. In her typical spur-of-the-moment but well-choreographed style, Maud dispatches The Problem in a way that is supremely ironic, and she gifts herself peace and quiet for Christmas.

Perhaps the most powerful moment of the entire collection appears as a sort of aside in the third story: Maud’s memory of her sister Charlotte. Eleven years older than Maud, Charlotte was crippled by mental illness and served as anything but a maternal figure for Maud, who was forced to care for her older sibling until her tragic death. “Charlotte had died thirty-seven years ago. Only then had Maud’s life begun. Better late than never, she thought.” Through this example of Maud’s biting, sardonic humor in the face of immense personal loss, Tursten examines Maud’s yearning for that which her sister could never provide: deep, genuine human connection. Maud’s memory of her sister is both fragmented and full, both frustrated and fond. Maud wanted her sister to be her sister, not a ghost wholly dependent on Maud’s care. And it is this connection that Maud searches for, and defends, through her murders. She kills those who feign intimacy to get what they want, and she uses society’s prejudice—and ignorance and dismissal—of the elderly to maintain her counterfeit innocence.

The final two stories revolve around the same crime—the murder of a local antique dealer. First, in “The Antique Dealer’s Death,” the narration breaks from Maud’s point of view and enters the mind of Richard, a retired journalist and author who lives in the same building as Maud. He attempts to insert himself into a police investigation about a murder in Maud’s apartment, not seeming to trust the female investigators. His amateur foray into the investigation allows Tursten to show Maud’s crimes from the outside looking in; Richard acts as a metonymic voice of a society that disregards old people—especially old women—and considers them incapable of much at all, let alone murder. Then in the final story, “An Elderly Lady Faces a Difficult Dilemma,” laced with affectionate remembrances of her father, Maud returns as the narrator to explain how she did it—and how she convinced everyone it wasn’t her. And, naturally, that the antique dealer had it coming. (He did.)

At once a meditation on growing old and a requiem for human connection, An Elderly Lady Is Up to No Good shines brightest when Maud reflects, when she pauses and ponders, when she remembers that which made her into the woman she is: her father, her sister, and those people who provided her with that vital human connection she now lacks and sardonically disdains—and, maybe unknowingly, chases.

University of Oklahoma