Electric Lit relies on contributions from our readers to help make literature more exciting, relevant, and inclusive. Please support our work by becoming a member today, or making a one-time donation here.

.

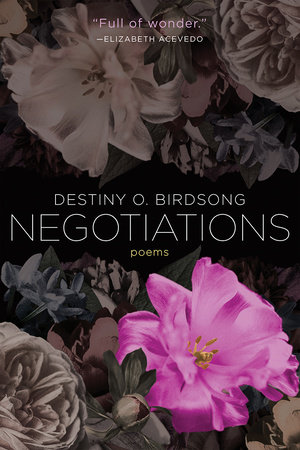

Destiny O. Birdsong’s debut poetry collection, Negotiations, is exactly what it sounds like. The speakers in this collection negotiate their body—asking what it’s worth to themselves, to romantic partners, to a society that caters to white people. The speakers negotiate with their memory, examining how trauma functions in their daily lives. The speakers negotiate with men, with their mother’s old sayings, with their health, with love or what was mistaken as love.

In this collection, Birdsong directly addresses those who have caused harm—such as rapists, racists, and others. She uses each poem to examine power or the lack thereof and explores what it means to be a Black woman in America, with her skin tone, her autoimmune disease, her hair.

Destiny O. Birdsong is a Louisiana-born poet, fiction writer, and essayist. She has received many fellowships, including Cave Canem and the MacDowell Colony. Her work has won the Academy of American Poets Prize, Naugatuck River Review’s 2016 Narrative Poetry Contest, and others.

I chatted with Birdsong about living with a chronic illness, renegotiating beliefs, and expressing anger as a Black woman.

Arriel Vinson: The collection starts with slavery and pink hats, and your pussy. Tell me more about the title poem and how you’re negotiating with your body—and other bodies—throughout this collection.

Destiny O. Birdsong: The title poem, “Negotiations,” is one of the earliest pieces I wrote for this book, and I did so during the summer of 2017, shortly after the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, which explains my references to the city. “Negotiations” also contains elements of the Women’s March on Washington, which happened earlier that year, and some of the bizarre suggestions I heard from white people in the wake of both the 2016 election and the Charlottesville rally (like political poisonings and sex as conversion therapy for Neo-Nazis).

In the poem, I was attempting to address the schisms between me and those people—not only in our reactions to the persistence of racism, but in our strategies for reclaiming democracy (or whatever passes for it in America). Those schisms always require a certain kind of “negotiating” for me as a Black woman: I appreciate white allyship, but I am always aware that even the activist imagination is a privileged terrain. So too is bargaining with one’s body; I was reminded of this with “Naked Athena,” who stripped in front of a line of policemen in Portland earlier this summer. The stakes of such acts are higher for Black women, and no one better embodies that than Sally Hemings, who came into the poem because of her connection to Charlottesville and because she had to negotiate what was, by definition of her bondage, a sexually violent relationship with Thomas Jefferson in order to free her children. She serves as a historical precedent for my negotiations in racist and misogynistic spaces as both a Black woman and a sexual assault survivor.

AV: Many of the poems in Negotiations consider worth: what a Black woman is worth, what or who is worth stealing or hungering for, who is stealing, etc. How is worth in Negotiations directly linked to power, the body, and money, or the lack thereof?

DOB: I entered adulthood believing that my body was supposed to retain a certain kind of social capital in order to be valuable and desirable, and that capital lay in things like beauty, health, and sexual purity. A lot of the poems in the book chronicle my renegotiation of those beliefs in the wake of illness and assault. Letting go of all that allowed me to see myself clearer, see my God clearer, and reclaim my power.

But of course, in spite of all this work, everywhere I turn I’m reminded of how little this world values Black women, which affects me personally in some specific and contradictory ways. I’m often misread as being not enough of something: not smart enough, not beautiful enough, and in some instances, because I have albinism, not Black enough to even speak about these issues. Many of the poems in the book address that, but I also made space for the worlds in which I feel safest and most loved: the private spaces that me and Black women I love create with and for each other. That’s what’s saved me. That’s where I draw my strength, but also my sense of self-worth. I wanted the book to tell the totality of this reality: the blister and the balm.

AV: There are poems in the collection where you wish harm on racists and others. We typically don’t see such public wishes for revenge, especially in a poetry collection. Why are anger and vengefulness useful in Negotiations?

DOB: Unprocessed rage can kill you. I’ve watched it happen to people in my family, and to people I love. But I also know that not all rage should be unleashed into the world. Since childhood, the page has been a safe space for me to process things I didn’t understand, or to interrogate some of the silences in my family. Now, it’s a place for me to take my rage; I know I can put it there and keep me and everyone else safe. But rage is also a revolutionary act, which is something we’re thinking a lot about in a year filled with protests of all kinds. Black people are so often expected to forgive, and I do, but I also need to make it clear that I am not superhuman, and I get angry at injustice. I get angry when I’m harmed for no reason. My rage reminds me—and hopefully everyone else—that I’m human. And if, as so many people have told us, poetry is a testament of the human experience, then rage belongs here too.

AV: Negotiations also navigates the speaker’s chronic illness. We see a call to Robert Hayden in relation to the speaker’s body on one hand, and a poem based on a hotep saying illnesses are man-made on the other. Why was it so important to give chronic illnesses space in this collection, and how are you negotiating with it in these poems?

Rage is a revolutionary act.

DOB: Living with a chronic illness is one of the many ways I negotiate space for myself—for my care—and misogynoir and class have just as much of an effect on how I do that as how I do anything else. And if I was going to talk about all the things I negotiate in order to survive, but leave that out, I only would have been telling half the story, which is something that already gets done so often to Black people in every space imaginable. I couldn’t do that to my body in these pages. And I couldn’t do that to the Black woman who might be reading this and needing to see someone like her, whose situation is complicated by illness, and whose life has been enriched by the ways she’s learned to live with it.

AV: Many of the poems interrogate—and reject—ideals of womanhood in relation to men. The speaker considers her own mother’s loneliness, the concept of keeping a man/losing a man, and being enough for one. Tell me more about this.

DOB: I was raised by a single mother whose dream was to get married, and in some ways, our family lived holding our breaths for that moment. We dreamt about it, we prayed for it, and when it finally happened it was nothing like what we imagined. Even so, I wanted that life for myself, and I believed I was supposed to do whatever it took to make that happen: be submissive, accept ill-treatment, contort myself to fit whatever mold my husband would expect me to. But none of it worked. Then I watched women I love enter these really dangerous unions, and the texture of their lives changed. And so did they. They got angry, bitter, or complacent. And when I was in similar relationships, the same things happened to me. The whole notion was harmful, and I knew it would stay that way until I let it go. But this was also happening as my relationship to my body was changing, so a lot of it had to be mapped out on the page for me to even make sense of how my ideologies were changing, and how I was changing. In some cases, I’m still discovering truths about myself that I wrote in these poems. For example, I’ll have a really good therapy session, or a great journal entry where I make some declaration, and suddenly a line from one of the poems will pop into my head, and I’ll think, “Damn, now I finally understand what I meant when I wrote that.” It’s wild how poems will do that to you.

AV: Trauma and memory are used often in Negotiations. The speaker remembers dialogue from men—such as her rapist—and it seems to permeate the speaker’s daily life. How do memory and trauma hold space in this collection?

DOB: I used to think I had an amazing memory—and perhaps I did as a teenager—but lately I am surprised by what I don’t remember, or how some of my memories get skewed: the order of events gets scrambled, or someone said something foreboding about their intentions, and that information will come back to me in a flash of hindsight. Some of that forgetting, I know, is a survival strategy, a way to let go of the recent traumas I’ve experienced with illness and hate crimes and assault, but some of it is ancestral.

I grew up in a family where several people died suddenly and/or violently, and we rarely talked about their lives because it meant remembering their deaths. One summer, my mother’s two closest siblings unexpectedly passed away within a couple of weeks of each other, and the following summer, her grandmother died. I don’t remember those years so much as I step back into that space in my mind, into the Louisiana heat and the itchy stockings and the acrid smell of funeral homes and my mother’s laconic, but suffocating grief. Only my senses return; I’ve blocked out almost everything else because it was so painful to witness. But in self-protecting, and in protecting my mother, I’ve lost something valuable. I can’t remember if she ever cried (though she might not have done that in front of us kids), or the first time she laughed again, or the first time I heard her singing to herself after that. Today, I value the memories of my experiences because they provide context for what was and is happening to me as I heal, but also because they remind me that I survived, and they give me little glimpses into how I did it. I need that for the future; if something else catastrophic happens to me or to someone close to me, I want to remember how I got over, how I came out. Poems can bear witness to this after the fact. They can preserve the narrative of survival that gets lost in the act of surviving.

AV: Throughout the collection, the speaker takes off her skin and either moves around without it, or watches someone else in it. In other poems, she admits to learning to love her body, but also hungers for it. Tell me more about this.

Poems can preserve the narrative of survival that gets lost in the act of surviving.

DOB: I lived my whole life hating my skin, wanting something different. I wanted to be darker, to more obviously resemble my mother or other people in my family (even though my mother and I literally have each other’s faces). Then, in my mid-30s, I developed a horrible skin condition as a side effect of a medication, and I lived with it for almost a year while my doctors tried to figure out what was wrong (or rather, tried to convince me that I had another auto-immune disease). For all those months, all I wanted was the return of my healthy, pale skin, and I had to admit that all the other times in my life when I thought I looked monstrous was the result of my own self-hatred, and the internalized ridicule I’d received from others. All of that was fabricated and subjective, but this condition was real. That experience changed me, and it changed me while I was writing these poems. Strangely, just as my skin got really infected, I started masturbating. I’m not sure if I connected it in my mind then, but in hindsight, I see it as an act of reclamation of my body, which wasn’t obeying any kind of logic at the time, and maybe also some nostalgic act for my skin: I was aroused by what was under threat of destruction and maybe I was finally understanding that what I stood to lose was in fact beautiful. That kind of irony is perfect for poetry, right?

AV: In all of these poems, you address capitalism, white privilege, sexism, and other means of oppression—sometimes outright and sometimes through more personal experiences. Why was this important in Negotiations?

DOB: These topics are…evergreen. It’s possible that Sally Hemings was writing about them 200 years ago in a diary we’ll never see, and here I am writing about them now because, just like her, they’re a part of my life. But I also write about them because I can’t think about them constantly. I have to make room in my head for joy, for hope and for conversations with my friends about recipes and gardens and paying off student loan debt. I have to live, but I also want to leave a record of how these things affected me and Black women like me. And once I put something on the page, it becomes more than just my experience, it becomes part of the Diasporic collective memory and the responsibility of non-Diasporic folks who read it, especially those who have the power to change things. I get tired of bearing that responsibility—and watching myself and other Black women do that work—alone.