Heidi Hammel, vice president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), most of the exoplanets discovered so far are in “the Neptune to sub-Neptune range” in terms of their size, yet these so-called “ice giants” have never been thoroughly investigated. “We’d like to change that,” Hammel told audience members at the annual Appleton Space Conference, which was held virtually this year on 3 December.

Heidi Hammel, vice president for science at the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy (AURA), most of the exoplanets discovered so far are in “the Neptune to sub-Neptune range” in terms of their size, yet these so-called “ice giants” have never been thoroughly investigated. “We’d like to change that,” Hammel told audience members at the annual Appleton Space Conference, which was held virtually this year on 3 December.

During her talk, Hammel laid out numerous reasons for sending spacecraft back to these icy outer worlds. The ice giants, she explained, have interiors that differ fundamentally from those of rocky planets like Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars. But they aren’t composed of hydrogen like Jupiter and Saturn. Instead, they are made of ices, which in astronomical terms are mixtures of various frozen stuff. Theoretical models suggest that both planets have cores composed of iron, nickel and silicates, but “the bottom line is, we don’t know what the interior is,” Hammel said.

Limited knowledge

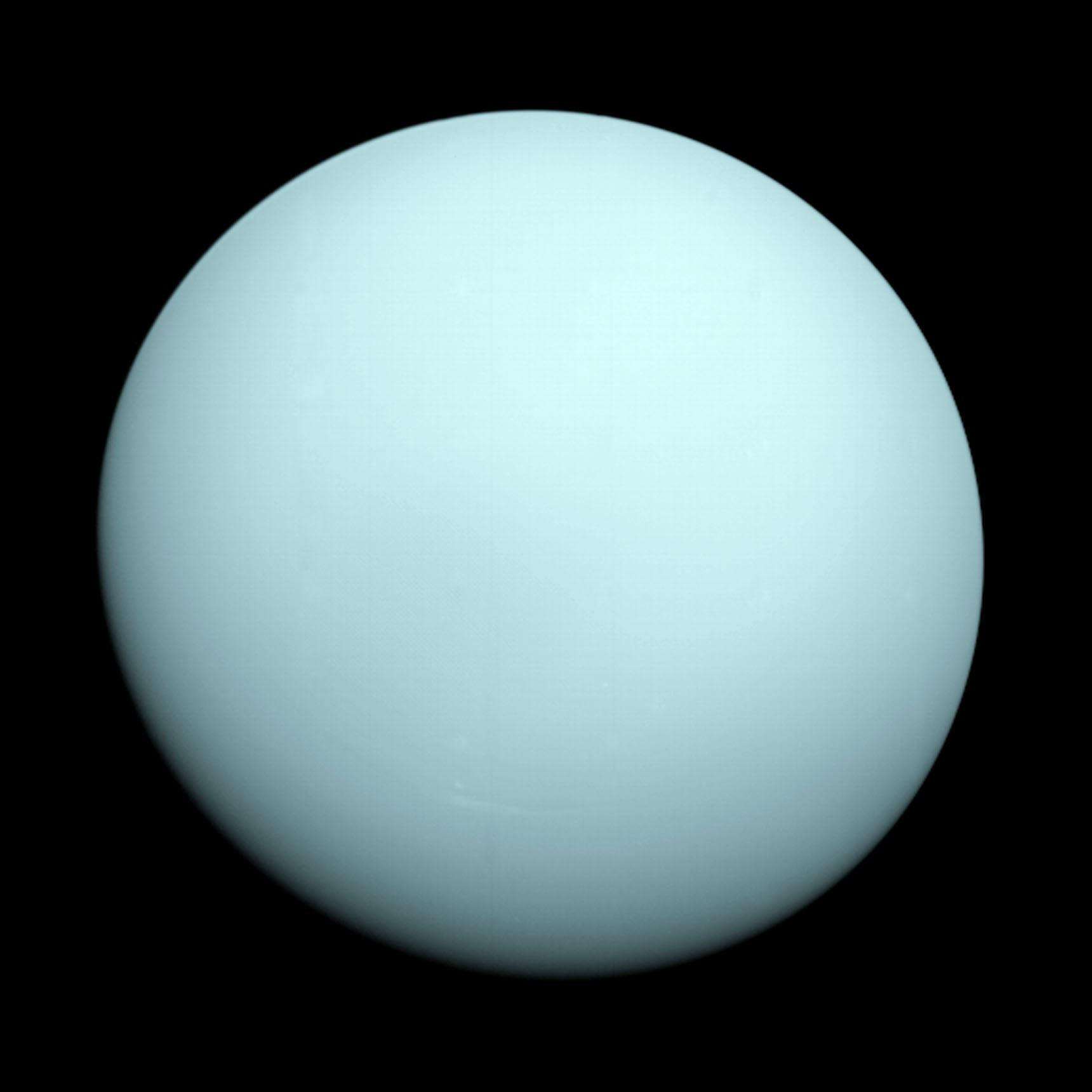

Hammel went on to explain that our knowledge of Uranus is especially limited because of the timing of the Voyager 2 flyby. For reasons that are not fully understood, but likely stem from an impact early in its formation, Uranus’ rotation is tilted at 90 degrees with respect to its orbit. This is very unusual for a planet, and unfortunately it meant that Uranus was in its southern solstice when Voyager 2 made its nearest approach. In this configuration, the planet’s northern hemisphere is completely dark – meaning that Voyager 2 couldn’t image half its surface (or half of its moons), and that half of it was not receiving any energy from the Sun.

This lack of sunlight helps to explain why images obtained during the 1986 flyby were, in Hammel’s words, “fairly dull”, with only 10 features visible. By 2004, when the 10 m diameter ground-based Keck telescope was trained on Uranus, it was a different story. With the planet now side-on to the Sun, Hammel noted, “funny things happened: the planet turned on”. Instead of a smooth, pale-blue dot, the Keck images showed popcorn-like clouds similar to the ones the Cassini spacecraft saw on Saturn. Similarly, an image obtained by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2006 showed dark bands that were absent when Voyager 2 made its historic visit.

Neptune, in contrast, was plenty active during its Voyager 2 flyby in 1989. At the time, it exhibited a huge dark patch on its flank that observers likened to the “Great Red Spot” on Jupiter. Within five years, though, images obtained by Hubble showed that Neptune’s dark spot had vanished. (Jupiter’s spot, in contrast, has been around for at least 400 years.) The dark spot was still absent in 2011, when Neptune was imaged again, but by 2016 it – or, rather, something like it – had reappeared.

The star of the Uranus-Neptune system, though, is Neptune’s moon Triton. This icy chunk of rock is a twin of the dwarf planet Pluto, and it was probably captured from the Kuiper belt by the pull of Neptune’s gravity. Unlike Pluto, though, Triton has active cryovolcanoes, and Voyager 2 flew past during an eruption that sent a plume of material 8 km into the moon’s tenuous atmosphere before the winds captured it. That makes Triton one of only five moons in the solar system known to be geologically active, and thus an attractive target for a space mission like the ones sent to explore the others: Saturn’s moons Enceladus and Titon (Cassini) and, soon, Jupiter’s moons Io and Europa (JUICE).

At present, no mission is scheduled for either of the ice giants. Though a Uranus orbiter was discussed during the last decadal survey for planetary science – a prioritization exercise conducted every 10 years by the US National Academy of Science, Engineering and Medicine on behalf of NASA – it wound up third on the list, behind missions to Mars and Europa. Several missions have, however, been proposed for the next decadal survey, including a Triton-only mission called Trident and a wider system explorer called Neptune Odyssey. And with the results of that survey due out in 2023, it’s certainly not too early for lobbying. Speaking with stuffed toy versions of Uranus and Neptune displayed prominently in the background, Hammel reminded her audience that Uranus’ rings are a particular mystery. It has grown new ones since the Voyager 2 flyby, and we know they are coloured red, blue and grey. But what are they made of? Where do they come from? So far, the answer isn’t clear. “We must send a spacecraft there to really study the rings in detail,” Hammel concluded. “We are all hoping that this is finally the era for going back to the ice giants.”