The IOP’s Teacher Training Scholarship programme provides an attractive route into physics teaching for recent graduates as well as mid-career scientists and engineers working across a range of industries

Recruitment and retention of specialist physics teachers remains a long-standing problem in England, with supply consistently falling short of national demand. Official figures from the Department for Education (DfE) in England, for example, show that there were 29,580 new entrants to postgraduate initial teacher-training (ITT) courses in the academic year 2019/20 – a slight increase on the 29,215 postgraduate trainees in 2018/19. Yet while subjects like biology, history and geography exceeded government recruitment targets, it’s notable that take-up was well below par in other subjects such as computing (79% to target), mathematics (64%) and physics (43%). What’s more, the shortage of physics teachers is even more acute for schools serving low-income communities with a history of academic underachievement.

As part of its strategy to address the shortage of candidates for physics ITT programmes, the Institute of Physics (IOP), which publishes Physics World, is aiming to encourage talented graduates and postgraduates in physics and engineering disciplines to enter the teaching profession via its Teacher Training Scholarship scheme. Funded by the DfE, the scholarships represent a compelling proposition, headlined by a tax-free financial package that helps would-be teachers transition through their one-year ITT course in England.

Support is substantial, wide-ranging and sustained. The IOP’s 2021/22 scholarship scheme, for example, is now open for applications and has 200 scholarships on offer to the next ITT cohort. Successful candidates will each benefit from tax-free funding of £26,000, with payment being phased throughout the training year and reinforced by a structured programme of continuing professional development (CPD) to complement trainees’ core ITT learning.

From industry to teaching

With the emphasis fixed squarely on recruiting outstanding physics teachers, it’s clear that IOP is casting the net wide, aiming to attract not just recent physics and engineering graduates into teaching but also established professionals with experience across diverse physics-based industries. A case study in this regard is Alastair Miatt, an IOP Teacher Training Scholar who completed his ITT course over the summer ahead of taking up a new physics teaching post in September.

After graduating with a mechanical engineering degree from the University of Cambridge in 1991, Miatt spent just short of three decades working in the automotive industry – a career that spanned a range of engineering management roles at Jaguar Land Rover (JLR) in the Midlands and the north of England. It was when Miatt turned 50, however, that he arrived at what he describes as one of those stereotypical “what am I going to do with the rest of my life?” junctures. Turns out the answer was teaching, a decision informed by his experience of voluntary work in the classroom – part of a JLR collaboration with All Saints Catholic High School in Knowsley that saw him mentoring sixth-form students with their engineering, design and technology projects.

“I’m a naturally conservative character, but my motivation was to do something fresh and take a leap with the next stage of my career,” he explains. “Although I’m an engineer by training, physics teaching was the natural choice. The fascination of physics is in helping young people to understand how the world works at a more fundamental level – that’s a powerful thing.”

For other mid-career scientists and engineers considering a similar transition, Miatt says the key is to recognize how all that accumulated professional experience can underpin success in the classroom – and, longer term, in making science relatable to young people. “There’s all sorts of expertise that you build up throughout your career and it’s easy to take that for granted or underestimate it,” he explains.

In Miatt’s own case, the industry perspectives from JLR offer so many different ways of relating fundamental physics concepts to real-world scenarios – the use of ultrasound sensors in self-driving cars, for example, as an applied case study illustrating the principles of wave theory. “The move into teaching is a big challenge for sure,” he adds, “but all the domain knowledge and skills from my time at JLR – whether that’s technical know-how, project planning or public speaking – has helped me rise to the challenge and embrace the change.”

A framework of support

For Miatt, and other career-changers like him, it’s evident that the journey from manufacturing plant back to the classroom would be that much harder – if not impossible – without access to the IOP Teacher Training Scholarship scheme. On a purely practical level, there’s the financial buffer to support industry professionals through ITT and into their formative years as newly qualified teachers. Equally important, notes Miatt, is the validation and recognition from one of the world’s foremost learned societies: “IOP is very supportive during the application process. Securing the scholarship was the real clincher – a massive vote of confidence in my potential as a physics teacher.”

That IOP support continues throughout the ITT year, with a series of physics-based online CPD events running alongside the day-to-day inputs that scholars get from their university ITT provider (the University of Chester in Miatt’s case) and in-school teaching placements. Prior to the coronavirus lockdown in March, for example, Miatt attended a masterclass on space science and gravity at the National Space Centre in Leicester. As well as providing an opportunity to compare notes and discuss common challenges with fellow IOP teaching scholars from around the country, he says the masterclass showcased the benefits of “venue-driven learning”, yielding all manner of simple, creative teaching ideas to incorporate into his lesson plans. “The IOP combines this deep understanding of physics education with great ideas about how to engage young people and communicate physics more effectively and creatively,” he adds.

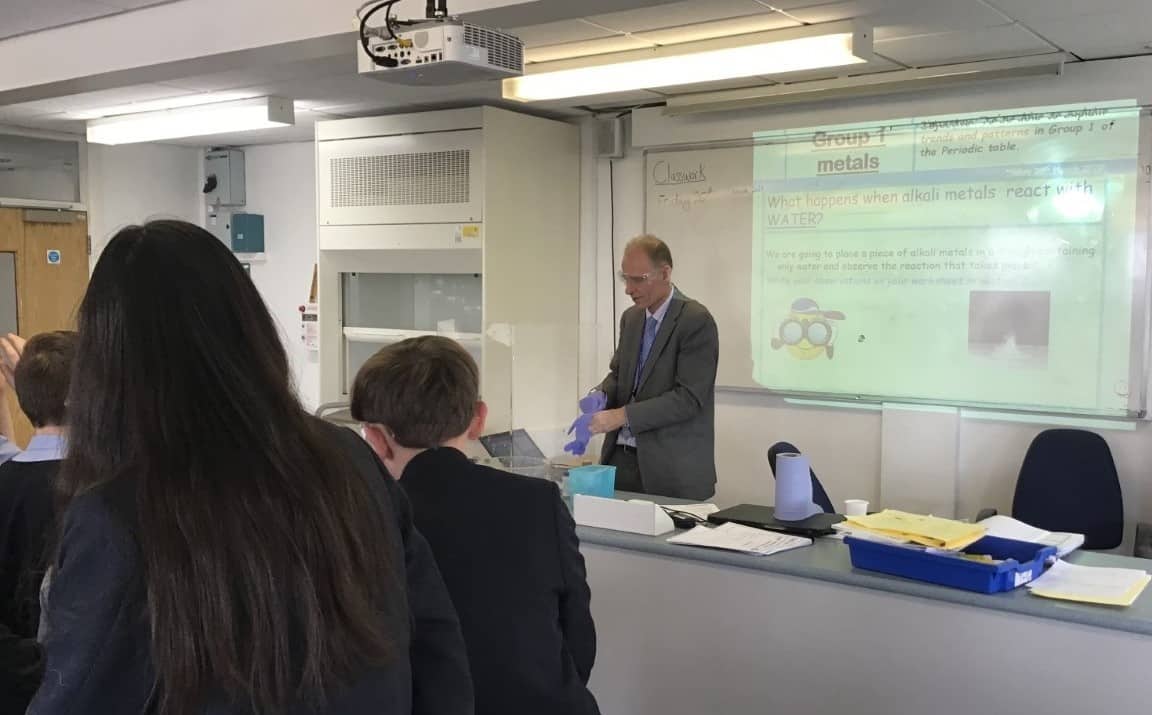

With the pandemic forcing school closures nationwide throughout the Spring, Miatt concedes that the disruption made for “a teacher training year like no other”. Nonetheless, with schools back open again and readjusting to the “new normal” since September, Miatt remains excited – and optimistic – after completing his first term as a newly qualified physics teacher – a post at Neston High School in Cheshire. “The notion that physics teaching can unlock a new world for young people is not too idealistic – it’s possible,” he concludes.