If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

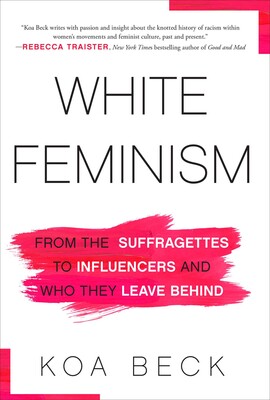

I interviewed Koa Beck not long before the coup attempt in Washington. I am writing this one week after that historic, horrific event. In the intervening period, a flurry of media coverage has focused on whiteness in America—its myths and privileges, its erasures and echo chambers, its facilitation of violence and oppression. In her book White Feminism, Beck, who among other prominent media roles was previously the editor-in-chief of Jezebel, examines the impact whiteness has had on the crusade for gender equality. What she finds is as pervasive as it is toxic.

“When I trace the phrasing ‘pro-woman’ through the length of my editorial career,” Beck writes, describing workplaces, policies, and groups that claimed the mantle, “I always end up in the same place: white feminism… stealthily positioned as being all-encompassing.”

According to Beck, white feminism is a “practice” and “state of mind” in which gender equality is a matter of “personalized autonomy, individual wealth, perpetual self-optimization, and supremacy.” Instead of questioning power structures, it embraces them, “replicating patterns of white supremacy, capitalistic greed, corporate ascension, inhumane labor practices, and exploitation, and deeming it empowering for women to practice these tenets as men always have.” (When I caught up with Beck after the assault on the U.S. Capitol, she emphasized that “white feminism has inherited a deliberate and structural lack of racial literacy from white supremacy.”) With its narrow focus on the self, white feminism is also seductive. “It positions you as the agent of change, making your individual needs the touchpoint for all revolutionary disruption,” Beck writes. “All you need is a better morning routine, this email hack, that woman’s pencil skirt, this conference, that newsletter.”

Beck is talking, of course, about Lean In, The Wing, the commodification of feminist slogans, wellness culture, Girl Boss, and so much more. But white feminism isn’t new—far from it. Her book details, for instance, how white feminism shaped the fight for women’s suffrage, rendering it less radical and less inclusive than it could, and should, have been. As is so often the case in the story of America, the people negatively affected by the forces of white feminism are people who aren’t white. “Women of color are poor people are being left behind, and yet the trappings that uniquely target us”—Beck is a queer woman of mixed race—“like poverty incarceration, police brutality, and immigration, aren’t often quantified as ‘feminist issue.’”

White Feminism mixes criticism with reporting, history with memoir. Ultimately, though, it is a manifesto: Beck is calling for collective action to demolish white feminism and build something better in its place. We talked about how that might happen, and when. With its unprecedented combination of devastating events (a pandemic, right-wing insurrection) and positive ones (Black Lives Matter), there’s no time like the present to start pushing for meaningful change.

Seyward Darby: This book is in part about who has power over language and ideas—for instance, who gets to decide what feminism is. You note that white feminism has become the most dominant form of the concept because white women have had the power to make it so. What distinguishes it from other forms of feminism?

Koa Beck: Feminism as an ideology has been explored, advocated, organized, and lobbied for by a lot of movements of people. I really wanted to make sure to underscore that that Native people have had their own gender rights movement for a long time, same with Chicanas, same with Black feminism, and same with Black lesbian feminism. The only ideology arguably that isn’t aware of that is white feminism.

I don’t think white feminism is feminism, but when I was doing archival research, reading reports from suffrage meetings, you would think that they thought they invented feminism. In fact, there had already been a lot of efforts by women of color and working-class women, especially immigrant women around the turn of the century. They were working in laundries and factories and pushing against being exploited with low pay, no bathroom breaks, no emergency exits. It was very much a feminist uprising to challenge their powerful employers with a union presence and walk-outs.

But a lot of the mechanisms by which we can challenge power on a structural level white feminism does not advocate for. That was true in 1920, and it’s also true in 2020.

SD: That leads me right to my next question. Can you talk about the ways in which white feminism has never been interested in seriously rocking the economic and social boat?

KB: White feminism always wanted to partner with consumerism. One of the P.R. challenges for what we think of as modern suffrage—so women in 1915, ‘16, ‘17, who were white and middle to upper class—was that women who spoke publicly about their opinions were often considered deviant. They overcame that challenge by signaling that suffrage didn’t really challenge what women were supposed to be. A suffragette was white, thin, able-bodied, and middle-class. If she was not a mother already, she wanted to be. A lot of early suffrage representation is of a woman either clutching a baby or holding a child. She also aspired to shop. White suffragettes saw that they could use companies like Macy’s, which sold a branded outfit for women who supported the vote, to relay their messages for them: They weren’t advocating for women to be too autonomous. Women would still shop and support the economy, still have children, still be a mother and a wife.

SD: So what’s changed since then?

White feminism has always aimed to partner with power, as opposed to re-interpreting it, dismantling it, or redistributing it.

KB: The scale of the corporate endorsement of white feminism. White feminism as an ideology and a practice has always aimed to partner with power, as opposed to re-interpreting it, dismantling it, or redistributing it. It’s reached new heights in my lifetime and career. In newsrooms, covering gender and gender rights, I would weirdly find myself in these lanes with the Lean In crowd. And that [white feminism] was supposed to be the extent of my beat or what the story was.

SD: Various entities and individuals come in for criticism in your book, including The Cut, Sheryl Sandberg, The Wing. You also describe Beyoncé’s performance at the 2014 MTV Video Music Awards, where she had a huge sign that said FEMINIST behind her on stage. You write that initially, like a lot of people, you thought it was a progressive moment, but that you later changed your mind. I’m hoping you can explain why. Do you see Beyoncé as practicing white feminism?

KB: We need many books on Beyoncé’s feminism. I encourage other writers to go there. I feel like I can’t comment on her feminist politics, mostly out of respect for her, but also because I know so little about the infrastructure of her enterprise. She operates culturally so differently than other public figures I cite the book. I will say that, as powerful as that moment was, my skepticism grew not so much from watching Beyoncé than it did from seeing how the performance seemed to set in motion a lot of white-feminist mechanics, specifically for marketers and P.R. people. Because Beyoncé had made this declaration, it took on the tenor of a trend, which is always kind of dangerous. Unfortunately, people try to capitalize on a moment regardless of their own ideologies, whether they’re overtly feminist or not.

SD: Is a more revolutionary, inclusive version of feminism incompatible with American capitalism? Put another way, if a young woman aspires to lead a corporation, can she really be a feminist?

KB: From a historical standpoint, a lot of movements led by women and people of color have been clear in their belief that the revolution for gender equality can’t happen under capitalism.

As for me, thinking about a lot of corporate environments that I’ve walked in and out of throughout my career, I think that the hard and fast rules of capitalism need to go. What I mean when I say that is this endless, endless more that has to be accrued. It is the force that maintains a lot of oppression. Whatever you achieve as a performance metric is never enough. In interviewing women, what I’ve encountered is that there needs to be a scaling back of that idea. So if a company is willing to lower performance metrics so that parents can take paid leave, I would consider that to be a good thing. If it were willing to scale back production expectations so union members can actually have time off, I would consider that a good thing. I would put the question to the companies and corporate people who are engaging with this book. If you can square the dynamics of capitalism specifically with people’s needs, I invite you and dare you to do it.

SD: Let’s talk more about solutions then. What can institutions do, and what can individuals do?

KB: One of the key components of a lot of these broken systems that we’ve been talking about is that they individualize us. They award us accolades to distinguish us from one another or, as we saw with the stories that came out of the #MeToo movement, they issue personal threats, all to maintain the system as it is. The best frame of mind, then, is to not think as individuals. Think more collectively with other women, actually approach and work with them to dismantle narratives and power structures or thinking of ways around them. I don’t think the answers are individualized.

SD: You talk about ways in which in various leadership roles in media you worked to change systems or policies supported by white feminism. I’m wondering if you have any regrets—situations where, looking back, you realized you were falling back on white feminism to guide you.

A lot of movements led by women and people of color have been clear in their belief that the revolution for gender equality can’t happen under capitalism.

KB: I definitely regret, towards the earlier part of my career, not thinking in terms of union organizing. I wasn’t a part of a union until I was at Jezebel. Prior to that, my strategy for going up against power was basically saying, I will not ask the staff to do that. Or, I don’t think that’s an appropriate use of resources. I would go to a meeting and assert myself, puff myself up really big to say what I wouldn’t do. I do think that is a very white feminist narrative, thinking, I’m the executive editor, so I will just go in there and say no, and that will be the end of that.

At Jezebel, the dynamic was different. I would say, I’m going to talk to the union and I’ll be back. There was a whole organized body with me that makes decisions and weighs out scenarios for everyone. It was extremely helpful and more successful. And history bears that out.

SD: You started working on this book before COVID-19 happened. How has the pandemic shaped the way you think about white feminism?

KB: I turned in my final draft right before COVID struck. I saw the writing on the wall very clearly—the patterns of who gets exploited, especially in times of crisis, whose lives have no value, whose lives have a lot of value, who has the money to insulate themselves. My editor and I basically had like a very long email where we established that COVID needed to go into the book it takes so much of the material and puts it right in your face.

While I was waiting on definitive data, I was assessing: OK, if this if this is what the government is saying an essential worker is, I know those fields are predominantly made up of women of color. I was basically just sitting around, waiting for The New York Times article that said that. There were also a lot of gender differences at the top of the pandemic, in terms of assessing the threat. Women were surveyed as being a lot more scared and concerned, even though men had much higher fatalities from it. My assessment of that is women are very familiar with circumstances jeopardizing both the health of their families and themselves and their economic security. That’s true from lack of paid parental leave to getting a chronic illness and your disability not covering it. Women are already very attuned to this reality because of the way that we do not see them and their labor and their lives.

I’ve always been struck by how deeply, deeply, deeply sexist economics are. The way that we have envisioned our country in terms of money and value does not factor in a huge portion of how we all live and how we need to live in terms of caretaking for others, whether it’s children or elders or disabled people or the chronically ill. With COVID, we’re seeing that in a hyper-distilled way. I think there’s a good opportunity to rebuild something better that holds businesses and the government accountable.