If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

When I started keeping a diary at twelve, it was in English. The daily newspapers we read at home were in Hindi, but to foster a better understanding and faster learning of the language, my father had subscribed to an English business daily as well as an English national daily. In school we were penalized a hefty 5 rupees for every word spoken in Hindi. At age five, I was awarded Best in English by my class teacher. In the subsequent parent-teacher meeting she asked my parents the recipe behind my success in the language, to which my father had replied jokingly, “We talk in English at home.” We didn’t, but it sounded good.

For my family, friends, relatives, and teachers, English was seen as a language of access. It could land you better jobs, remove limitations, and open up avenues. English speakers were high achievers, often conflated with the colonizers who ruled over us for about 200 years. It was ironic that the language of our colonizers was seen as aspirational, something that could lift us out of the discomfort that our parents’ mid-level jobs put us through. In reading all the subjects at school in English, we were made to understand that English was the language of possibilities. My cousins who studied in Hindi schools wouldn’t have all the opportunities that would have been available for me.

Torn between these two worlds, I found accidental love in the language that was imposed upon me.

Torn between these two worlds, I found accidental love in the language that was imposed upon me. From a young age of six or seven I started voluntarily, subconsciously veering towards reading and writing in English. Every April we would get new books for the next class. I would cover them with brown paper, stapling all four corners secure, and then dive into the stories within.

After the end term exams in March, we would get a short ten-day break before starting the new session. During this break we would get to buy new books, notebooks, prepare school uniforms and bags for the new session. By the end of the week before school re-opened, I would have finished reading all the short stories in the English and Hindi coursebooks. An introverted child prone to reading in heaps almost always alone, I would then go on to keep a notebook called the “rough copy” and jot down all the thoughts I had after reading those stories. I chose to write them in English to keep my parents thinking that I was doing something of value, importance and related to school. In fact, subliminally I was drifting further into a self-structured culture of reading in the language of my colonizers.

The year 2020, full of challenges as it was, was also the year I started publishing non-fiction. When I graduated from writing for myself to writing professionally, my chosen language of publication was English. I had worked as a reporter for several national English dailies before, but this writing was for myself alone. It did not come as a surprise to me. Through the last five years I had tried to rebuild my relationship with Hindi. I bought books, read them, albeit very slowly. I sometimes wrote in Hindi, too. When the mood struck, I would type messages in the Devangiri script to friends, family, and especially my mother on WhatsApp. I tried hard to read and re-read Hindi literature writers I had grown up reading, to reignite a spark where there was a long-existing deadness. Despite it all, I kept falling behind. One way or the other, I would lose patience, procrastinate, or simply lose interest and put off reading or writing in Hindi to another day.

Learning English was equivalent to being aspirational, ambitious, and striving.

In April 2020, when my first personal essay was published, I found myself at an impasse. A dilemma confronted me: Why was I writing in English? The more I tried to think about it, the more the answer eluded me. Once again I sat through long afternoons watching interviews of writers in Hindi on YouTube. Understanding the language was not a problem, but I had been brought up to think of Hindi as an obsolete tool. A knowledge of Hindi language alone did not ensure a great career. Drab government jobs, teaching opportunities in the heartland, and a clutch of other such limited avenues would be available to people who did not know the English language. Learning it was equivalent to being aspirational, ambitious, and striving. As kids, my brother and I were often produced before relatives and family friends to recite a poem in English, or just reel off a passage from Shakespeare. Back then, it was a marker of respect, class and being upwardly mobile. But personally, English meant a remove from my daily life, a place wherein I could hide and be by myself reading, writing, existing.

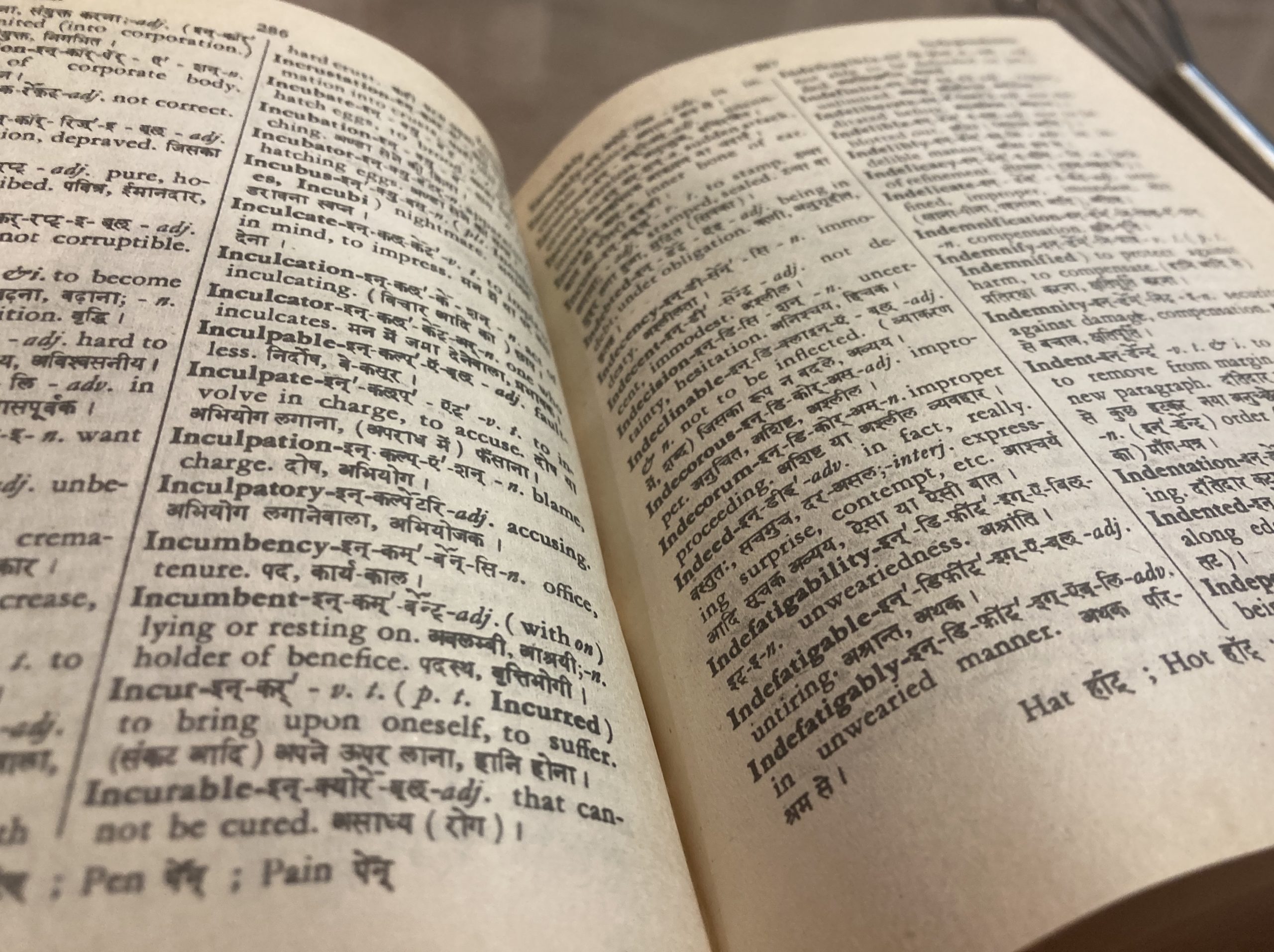

And English had its own talismans. In standard five my English teacher Priyanka Gulati told us, a class full of about 47 children, that any student’s best friend is a dictionary. She made this remark specifically to English, making me think about the language in another new way. While we did have a Hindi to English dictionary at home, getting an English to English one piqued my interest. It opened up my vocabulary, loaning me more time and showing me ways in which the language could be used. This was more than fifteen years ago, and I remember those words crystalize in the inner recesses of my mind. Since then, till about five years ago, I would buy a small English dictionary every now and then, keeping it in the pocket of my clothes, or in the small sling bag I always carried. A pencil, a dictionary, a notebook—these have forever since kept me company through my three big career moves across seven cities in two countries.

Whenever I sat with an English storybook, or an English language newspaper in hand, reading it, that paraphernalia—pencil, notebook, dictionary—was my little fort of protection. The language opened vistas for me that were inviting. They were happier, lighter places of joy, winters, snowfalls and Daffodils. Short stories by Kathrine Mansfield, Anton Chekov, Leo Tolstoy and Guy De Maupassant in English, became a portal to a new, richer place I was not content being a mere visitor to. Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore’s short story The Postmaster was inviting to me because the details in English language kept me hinged. It was a thrill to discover that a place in India could be written about in a foreign language (English) in a way that would become accessible to me. Similarly, I felt a pull each time I read something in English, realizing that my experiences in Hindi could be translated and written in English for someone, anyone to read.

I was raised speaking French, and did not begin learning English until I was nearly 7 years old. Even after that, French continued to be the language I spoke at home with my parents. (I still speak only French with them to this day.) This fact inevitably affects my recall and evocation of my childhood, since I am writing and primarily thinking in English. There are states of mind, even people and events, that seem inaccessible in English, since they are defined by the character of the language through which I perceived them. My second language has turned out to be my principal tool, my means for making a living, and it lies close to the core of my self-definition. My first language, however, is coiled underneath, governing a more primal realm.

This passage from Luc Sante’s essay Living in Tongues correctly captures the crux of my relationship with English and Hindi. With liberalization, modernity, and technology making their way into our lives after 1991 (the year of national economic reforms, and also the year when I was born), the Hindi that I was so closely attached to also underwent a change. English so densely permeated the air outside our houses that we didn’t even realize when it started drifting inwards. With liberalization, privatization and globalization, as a nation we were moving forward, using English as our crutch to get ahead. In the years that followed, English started assuming a bigger role in the lives of all of us middle- and upper-middle class Indians. From being a luxury, it was moving towards a necessity. My mother’s office graduated from the use of typewriters to computers. This meant she shifted to using English has her modus operandi in office, coming home with books on the Gandhi family written in English. In this way, Hindi began fading farther back into my life as the lingua franca of my daily life with parents, relatives and close friends. A link to my own history, Hindi became the cotton pyjamas I wore at home, while English would be my uniform for school time.

Born to an erstwhile British colony, I have come to understand that heritage comes with burden of maintenance.

In 2021, while my speaking and thinking still continues to be dominated by English, I dream in a no-language grammar or in the Hindi of my childhood. When interacting with our house help or the vegetable vendor, I flit to the Hindi of my hometown. In this I get a peek at the myriad ways in which language dominates and controls how I navigate through life. Among the several parallels between life in my hometown, Kanpur, and Delhi (250 miles away) where I work, the omnipresence of Hindi is one of the most significant. In the years before, I noticed the small ways in which English took over my life; now I notice Hindi overlapping and projecting itself, almost as if asserting its tiny presence over the larger-than-life façade that English casts over us. While talking to my boyfriend, at times, I slip unknowingly into Hindi. This is new—it didn’t used to happen in mid-2018 when we started going out—and it makes him uncomfortable, because his first language is Bengali. I make him understand then that as I am growing older in Delhi, so close to home, my English is beginning to gather a thin patina of Hindi.

Born to an erstwhile British colony, I have come to understand that heritage comes with burden of maintenance. And it has certainly not been easy for India to chart its own path after independence. Some of the more enduring legacies of the British Raj continue to form a big part of our identity and symbolize much of what is right and wrong with it. The English language tops the list. India’s 2011 Census showed English as the primary language of 256,000 people, the second language of 83 million people, and the third language of another 46 million. This makes it the second-most widely spoken language after Hindi.

In my 30 years of life in India, I have traversed the long route of understanding and learning English as the ticket to a better life to now dealing with the language English in a routine, almost mundane way. When I went to school, my parents wanted me to learn the language so as to secure a better career. Now, English has become the language across all kinds of workplaces. Across these diverse workplaces, it is a unifying language, but the way in which it is employed and spoken differs vastly.

Each morning, when I buy vegetables from the vendor outside my house, we talk in Hindi, but we always sign off the transaction in English. I say a thank you and almost always, if he’s not in a crushing hurry, Raju replies with a simple, “You’re welcome, didi.” The recent Census confirmed that English in India is no longer a foreign language, and I see this in my life as well. The colonial language has also become a unifying medium of conversation.

But it still carries colonial legacies. Since I arrived at the language from school and in the spoken way, I tend to use long, complicated words for seemingly mundane things, words that no native English language speaker would use. When I get a word wrong in its meaning or usage there is an instant pang of shame, that is unlikely to be found in any native speaker. A lot of Indian writing in English still continues to be in a “flowery” version of the language that makes for difficult reading. Friends have found it tough to read some of my earlier writing without referring to a dictionary. I now realize that these are colonial burdens, shames that we have carried forward without realizing their nature and gravity.

The fact that English is my colonizers’ language makes me queasy. It was an unintended gift, acquired at the cost of a lot of lives.

The fact that English is my colonizers’ language makes me queasy. It was an unintended gift, acquired at the cost of a lot of lives, money, and years of suppression. Shashi Tharoor, Member of Parliament, Lok Sabha, in his book Inglorious Empire writes, “That Indians seized the English language and turned it into an instrument for our own liberation was to their credit, not by British design.” The English language in India has now moved on from being just a language to a way of life, a common ground. But it’s important to remember that it was initially employed as a tool to rule, divide and suppress us. These were the words of Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay when he wanted to introduce the language in India: “We must do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern; a class of persons Indians in blood and colour, but English in taste, in opinion, in morals, and in intellect.”

Writers like Sante and Vladimir Nabokov, who also learned English as a second language as a child, have a control that is superior to that of most native speakers. They write fluidly, with grace, pulling the reader intuitively into their worlds. While I am yet to let go the pedantic ways in which I use the English language, I also continue to read and mend my relationship with Hindi. While I am acutely attuned to the ways in while English defines the colorisms of my daily experience of life as it is lived, I also look at being once again a fluent reader and writer of Hindi.

Luc Sante in his essay Lingua Franca writes, “In order to write of my childhood I have to translate. It is as if I were writing about someone else. As a boy, I lived in French; now, I live in English. The words don’t fit, because languages are not equivalent to one another.” This mirrors much of my life as a kid, so much of which was lived in Hindi. Now, at 30, as I continue to find my place in the writing world, I believe I could live in either of the languages—Hindi or English—but I choose English. It’s a burden, carrying the heavy weight of a colonial legacy forward, but in doing so, I have also found a struggle and language unique to me. Sometimes it does occur to me that I might not have an authority over either of the languages, but like Sante, it also lends me an advantage of mobility. In drifting between them, I could be anywhere or nowhere at all.