Browsing a Copenhagen airport bookstore, a translator picks up a book. The journey between that impulse and his eventual translation of the memoir into English was both emotional and serendipitous.

In the summer of 2016 I was passing through Kastrup Airport in Copenhagen with my wife, on our way home after a visit with family. We stopped to browse the bookstore, and I noticed a reprint of a book by Danish author Tove Ditlevsen called Gift, which had first been published in 1971. I hadn’t read much of her work, but I knew she was a big name, so I bought it, even though the cover was strange, a psychedelic skull on a gray background.

It did not take more than a couple of sittings to devour this memoir of Tove Ditlevsen’s life from the ages of about twenty-three to thirty-five. It chronicles her rise as a best-selling author, while she also had four failed marriages, two back-alley abortions, and a five-year near-fatal addiction to the opioid Demerol. I distinctly remember laying the book down after the final page and thinking to myself, I think this is a masterpiece. This was an intuitive judgment, not a conclusion I had come to after analyzing the text. But looking back now, I think what caused me to deem this work a masterpiece is the combination of Ditlevsen’s writing style, which is concise, honest, and ironic, combined with the content of her story, which through her many troubling experiences pulls back the veil on dependent behavior and addiction in a deeply personal yet universal way.

After determining that Gift had never been translated into English, I immediately began the process to get a letter of permission. This took about a month, involving a couple of inquiries and follow-ups with the Danish lawyer in charge of Ditlevsen’s estate. When I received written permission to translate and seek publication, I then applied for a grant from the Danish Arts Foundation, which has a program to underwrite sample literary translations of about twenty pages, which translators can then use to pitch the books to publishers. Within a couple of months I received the grant and had finished up work on my book of poetry translations by Benny Andersen, Something to Live up To, so I began at page 1 of Gift.

My process, similar to most literary translators, I imagine, is to be led by the text. I weigh every phrase in the original and attempt to re-create it in English as if the author had written it in English, with the same tone and emotional charge. I try to keep the style intact, including attention to sentence length and punctuation.

Ditlevsen writes in a controlled, colloquial, confidential tone, so I needed the English text to reflect that.

There is a balancing act occurring, treading a fine line between using the Danish phrasing and changing whatever needs to be changed so it will read effortlessly in English. Part of this includes sensitivity to the emotional content, which is often signaled by the register or tone of the vocabulary. Ditlevsen writes in a controlled, colloquial, confidential tone, so I needed the English text to reflect that. When I am translating, I often feel like an actor may feel, learning lines and then reciting them with the emotional intent of the character. Similarly, I take the text into my body and feel the emotional impact, so I can re-create the impact through the English text.

As I proceeded to complete the sample translation I was feeling satisfied with the result. I felt like I was meeting Tove through her text and re-creating the impact of the original. I felt validated in my choice and judgment of the book as a masterpiece, and I didn’t want to stop. So I didn’t. Though I didn’t have a publisher, I felt sure I would find one, so I kept going, translating the rest of the book on spec.

To do it justice, I had to empathize with the text on a deep level. I was on Tove’s side. I wanted her to succeed.

Anyone who reads this book can’t help but be struck by the many turbulent events of Tove Ditlevsen’s life. The translation process is not the same as reading. Translation is slower and more intimate, as I weigh, embody, and reframe each phrase. To do it justice, I had to empathize with the text on a deep level. I was on Tove’s side. I wanted her to succeed. I was captivated by her talent, her honesty, and her determination to be true to her art. Yet she kept making these self-destructive decisions, like cheating on her husband at a college party, and having an unnecessary ear operation, which left her deaf in one ear. It was as if she had certain blind spots, and she was unable to see the many options available to her as a successful writer.

I distinctly remember when I arrived at the end of part 2, chapter 5. Tove had just been carried out of her house after her long addiction. She was down to sixty-five pounds, fortunate to be alive, and placed in an ambulance to be driven to rehab. I remember calling my wife into the living room from the kitchen, to tell her what had just happened to Tove. Then it dawned on me that when I turned the page, to keep translating, Tove would be going through withdrawal. I recalled from my first reading that this was some of the most excruciating writing I had ever experienced. I realized that there was no way around it. She would be going through it, and I would be going through it with her, in my own way. I broke down sobbing in my wife’s arms.

I realized that in having translated the book thus far, I had been going through some secondhand trauma.

I realized that in having translated the book thus far, I had been going through some secondhand trauma. I had been deeply moved and triggered by Tove’s struggles with love, anguish, and addiction, and I needed to sort that out before being able to continue. So I decided to put the book on hold for two weeks, something I had never done before with a translation project. During that time I set up lunches and phone calls with friends and family. I talked about this book and process with them, and I wrote and meditated.

I paid particular attention to the idea of dependent behavior. I thought about my uncle, who bankrupted his family by incessant gambling. I would bet that everyone knows someone who has had a brush with dependent behavior or addiction. Then I realized that I am that way too—that I also have blind spots, that I have used work, and other compulsive behaviors, to cover up or escape from difficult emotions. I came to believe that there is a spectrum of dependent behavior to which all people are vulnerable. Whether it is drugs, food issues, smoking, drinking, work, sex, shopping, gambling, or something else, there are plenty of dependencies to choose from. And I think our society encourages overconsumption and emotional avoidance. But if a person goes off the rails, like Tove, and becomes self-destructive, then they are usually blamed for not having things under control.

Tove Ditlevsen never preaches in Gift or philosophizes like I’m doing. But by exposing her story, I think she uncovers a shadow in our society, where we tend to alienate and judge people who have dependency issues, instead of providing the support and compassion they need.

Eventually I felt emotionally strong again, and I returned to work and finished translating the book. I still needed a title and a publisher. Luckily I went to the ALTA (American Literary Translators Association) conference in the fall and was discussing the book with my roommate, Sebastian Schulman. I offered my feeble attempts at a title, and he very casually blurted out the suggestion, “How about ‘Dependency’?” So all I can take credit for is realizing genius when I encountered it. I love how the word dependency hints at marriage and relationship, in addition to the more obvious definitions. As you may know already, Gift in Danish translates into both “poison” and “married”; a brilliant title in Danish that has no English equivalent. But, I think, with Sebastian’s help, we did okay in that regard.

Finding a publisher was more difficult than I thought it would be. I sent out samples from the book, or the entire book, to about a dozen publishers, ones who accepted unsolicited manuscripts. I did not have access to major publishers, having no agent or contacts in that realm. After about a year I received all rejections or no responses. Disappointed, I turned to the small publisher I had been working with on my other books, Spuyten Duyvil Press, and asked him to take on the book, which he was happy to do. But when he wrote to the Danish publisher, Gyldendal, for the rights, they turned him down.

I was surprised and wrote to the rights manager at Gyldendal to find out why they had rejected his offer. She responded that she knew other larger presses who were interested in this book. That was news to me, and I wrote back to her asking who those presses were, and if she could put me in contact with them, considering I had the entire book translated into English. I didn’t know if she would or could do that, but I figured it didn’t hurt to ask.

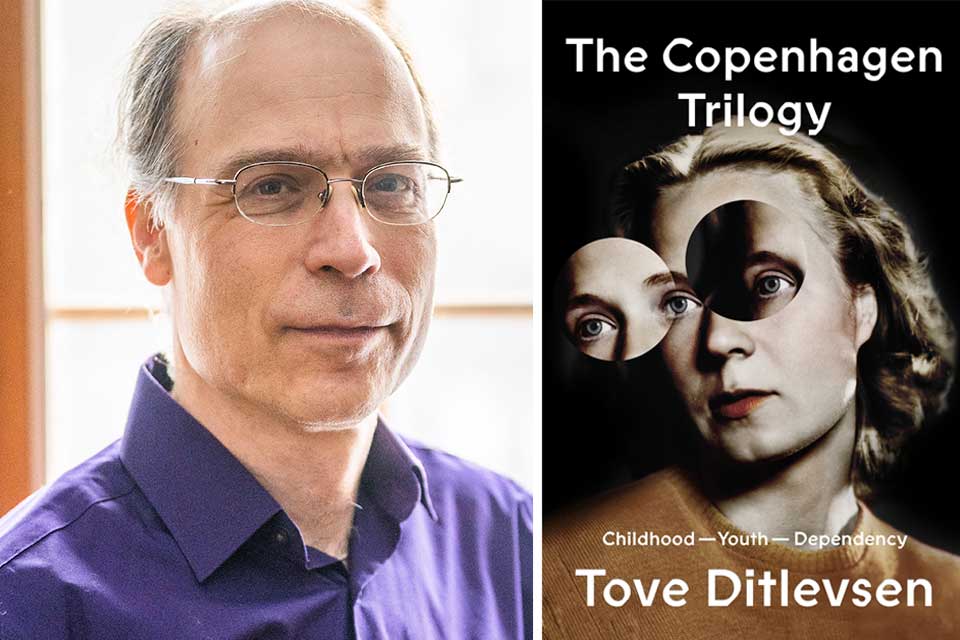

The Gyldendal rights manager wrote back with two email addresses, wishing me luck. I sent my manuscript to both and then left for a weeklong writing conference in Vermont. Within days I received an email from the Penguin Classics editor that she wanted the book and would be presenting it to her colleagues that week. They wanted it. When I got home I was contacted by the second publisher, with whom I talked for an hour on the phone. He wanted it too. Evidently there was a bidding war, and Penguin came out on top. It was now late 2018. The book would begin production and launch in September 2019, as part of a trilogy.

What I did not know is that while I had been submitting my manuscript to various publishers, Penguin had sent an editor to the Frankfurt Book Fair, looking for a major female Scandinavian writer to promote. The editor inquired at the Danish Arts Foundation table there, and Tove Ditlevsen was recommended to them. The Penguin editor had then contacted Gyldendal to get more information about what books by Ditlevsen would be good candidates. Of course I had no idea about any of this when I was sitting in my office translating the book and then pitching it.

More so than with any other book I have translated—though I believe in all of them—I felt from the start that this particular book has the potential to be a catalyst for widespread social change; that if enough readers spend time with Dependency and the trilogy, it could produce a widespread shift toward more compassion for ourselves and for others, and more support and less judgment for people who struggle with dependent behavior. I know this is asking a lot of fate. But considering all the fateful events that brought the books out of Denmark, I am not ruling anything out.

Northampton, Massachusetts