If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

April 30, 1975—the day Americans helicoptered out of Saigon and Communist forces rolled in their tanks—goes by many names: the Liberation, the Reunification, the Fall. In the U.S., the day marked the end of two controversial decades of guerrilla warfare and the start of a reckoning for veterans who returned home with what would soon be named PTSD. In Vietnam, it launched the flight of hundreds of thousands of refugees on flimsy fishing boats, the beginning of skirmishes with Cambodia that would climax in the invasion and occupation of Vietnam’s neighbor, and the first attempts to rebuild a nation that even today bears the legacy of Agent Orange.

For people who exist thanks to the small successes of those fishing boats (between 10 and 70 percent of refugees died at sea), the day is suffused with nostalgia for an expired yellow-striped flag and the eerily steady voice of Khánh Ly, who sings, much like Fairuz, of a beloved city left behind. Khánh Ly recorded “Em Còn Nhớ Hay Em Đã Quên” (“Do You Remember, or Have You Forgotten?”) two decades after Communist victors renamed Saigon as Ho Chi Minh City. Since then her lament has been covered by women and men alike; there are multiple karaoke videos for those who wish to warble their own yearning. Such music can be heard at gatherings of Việt Kiều, or Overseas Vietnamese, in Sydney and San Jose, Montreal and Berlin, even though the city they dream of has since been swallowed by a hypercapitalism that sprouts skyscrapers from dust.

This year is rich in new books from those who bear the legacies of that day: who can hear, even in pain, what Khánh Ly calls “the language of poetry.” These are my picks from the diverse writers shaped by the conflict in Vietnam.

A Thousand Times You Lose Your Treasure by Hoa Nguyen

Nguyen dedicates her latest poetry collection to her mother, who raised Nguyen after her American father’s desertion. Nguyen calls her “Diệp / Linda,” a nod to the bifurcated identities of people who depart Vietnam for America. In a black-and-white photo, Diệp slings a leg jauntily over a motorbike’s handles. The poems circle around Diệp’s life as a stunt motorcyclist in a Vietnamese women-only circus and the other dangers she skirts, such as the napalm developed at Harvard and manufactured by Dow Chemical that rains in:

8 million tons of bombs

in Vietnam Burns at

1,500–2,200°F (1/5th as hot

as the surface of the sun)

Very sticky stable

also relatively cheap

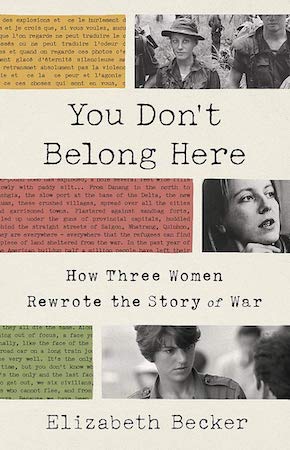

You Don’t Belong Here: How Three Women Rewrote the Story of War by Elizabeth Becker

Becker, who began her journalistic career covering Pol Pot’s rise to power in Cambodia, turns her focus to her female colleagues in Vietnam, plucking out the stories of an American, an Australian, and a French journalist. Becker draws on letters and interviews to tell the stories of women plunged into a mostly male world, where they encountered Western sexism in equal or greater measure than that which they’d already known in their home countries. Becker points to her own flight from sexist academia and into a war zone:

Soft spoken and to the point, she asked, Why had I crossed the ocean to cover a war?

The short answer was a nightmare I was all too keen to leave behind. My master’s adviser had rejected my thesis on the Bangladesh War of Independence after I refused to sleep with him. He said the one was not related to the other.

Everyday Mojo Songs of Earth: New and Selected Poems, 2001-2021 by Yusef Komunyakaa

One of the greatest living makers of the persona poem, Komunyakaa began writing as a journalist embedded with American forces in Vietnam. His forthcoming compendium of the past two decades flips between war and sex, showing them to be two opposite expressions of domination. They are also linked to each other, as the arrival of GIs in Vietnam, like that of many colonial or neocolonial forces in other nations, spurs the rise of local sex work. An excerpt from the sonnet sequence “Love in the Time of War” reveals the thin line between violence and love:

Bull’s-eye. Maggie’s drawers. Little Boy. Fat Man. Circle

in the eye. Bayonet. Skull & Bone. Them. Body count. Thou

& I. Us. Honey. Darling. Sweetheart, was I talking war in my sleep

again? Come closer. Yes, place your head against my chest.

Things We Lost to the Water by Eric Nguyen

Komunyakaa’s home state of Louisiana is today the site of a thriving Vietnamese diasporic community, mainly settled in the humid heat of New Orleans that recalls the climate they left behind. Debut novelist Nguyen follows one of these families as they cope with the memory of people and places they may never see again. That sense of loss is compounded with the arrival of Hurricane Katrina. In the nonfictional world, one of the symbols of Katrina’s destruction was the shotgun house, a narrow ranch in which each room doubles as a hallway to the next; they clustered in areas most vulnerable to flooding, and, before the storm, were primarily occupied by the city’s poorest residents. Nguyen’s family moves into one such place:

The wife told Hương it was called a “shotgun house.” Ngôi nhà súng, she clarified. “See?” she said. She placed the suitcase down and mimed the shape of a gun with one hand. With her other, she held her wrist. Closing one eye, she looked through an invisible scope and the appearance of intense concentration fell onto her face. For a few seconds, she stood silently, so focused on something in the distance that Hương looked toward where the wife stared, too. Then “Psssh!”—the imitated sound of gunfire.

The Truffle Eye by Vaan Nguyen, translated by Adriana X. Jacobs

The cover of this bilingual poetry collection is a shifting blue-green, appropriate for a language in which xanh can mean either color. But The Truffle Eye is in fact translated from Hebrew, the language of a poet born to two of the 360 Vietnamese refugees to enter Israel between 1977 and 1979. On facing pages, the poems grow right-left in Hebrew and left-right in English, pressing out from an unwritten and unreachable Vietnamese spine. In her introduction, Jacobs (whom I know and who gifted me the book), writes of Nguyen:

Her connection to this history is understandably complicated. In her words, “Whenever a humanitarian crisis pops up, I’m approached by various media outlets that want to interview me about the refugee experience, but the only thing I can do is read poetry at one of Maayan’s flash readings, because I am a poet who does not feel like a refugee.” Although her parents spoke Vietnamese at home, Nguyen feels most at home in her native Hebrew.

Afterparties by Anthony Veasna So

So died in December, a half-year before the release of his debut fiction, a collection of short stories that illuminates the lives of Cambodians who escaped the Khmer Rouge, as well as their descendants in the United States. The sadness with which So’s death was mourned is contrasted by the humor of his writing. Afterparties’ opening story, “Three Women of Chuck’s Donuts,” circles around fried dough and Khmer identity:

Being Khmer, as far as Tevy can tell, can’t be reduced to the brown skin, black hair, and prominent cheekbones that she shares with her mother and sister. Khmer-ness can manifest as anything, from the color of your cuticles to the particular way your butt goes numb when you sit in a chair too long, and, even so, Tevy has recognized nothing she has ever done as being notably Khmer.

The Committed by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Nguyen’s sequel to The Sympathizer races through a thriller plot while administering doses of postcolonial theory (discussed in my interview with the author for this publication). But its jewel is its prologue, a lyric account of fleeing Vietnam that is subtitled We and narrated from this plural point of view, demonstrating how the terrifying act of migration renders differences in class, religion, and other vectors temporarily insignificant: all are bound to the same odds of survival.

We were the unwanted, the unneeded, and the unseen, invisible to all but ourselves. Less than nothing, we also saw nothing as we crouched blindly in the unlit belly of our ark, 150 of us sweating in a space not meant for us mammals but for the fish of the sea. With the waves driving us from side to side, we spoke in our native tongues. For some, this meant prayer; for others, curses. When a change in the motion of the waves shuttled our vessel more forcefully, one of the few sailors among us whispered, We’re on the ocean now. After hours winding through river, estuary, and canal, we had departed our motherland.