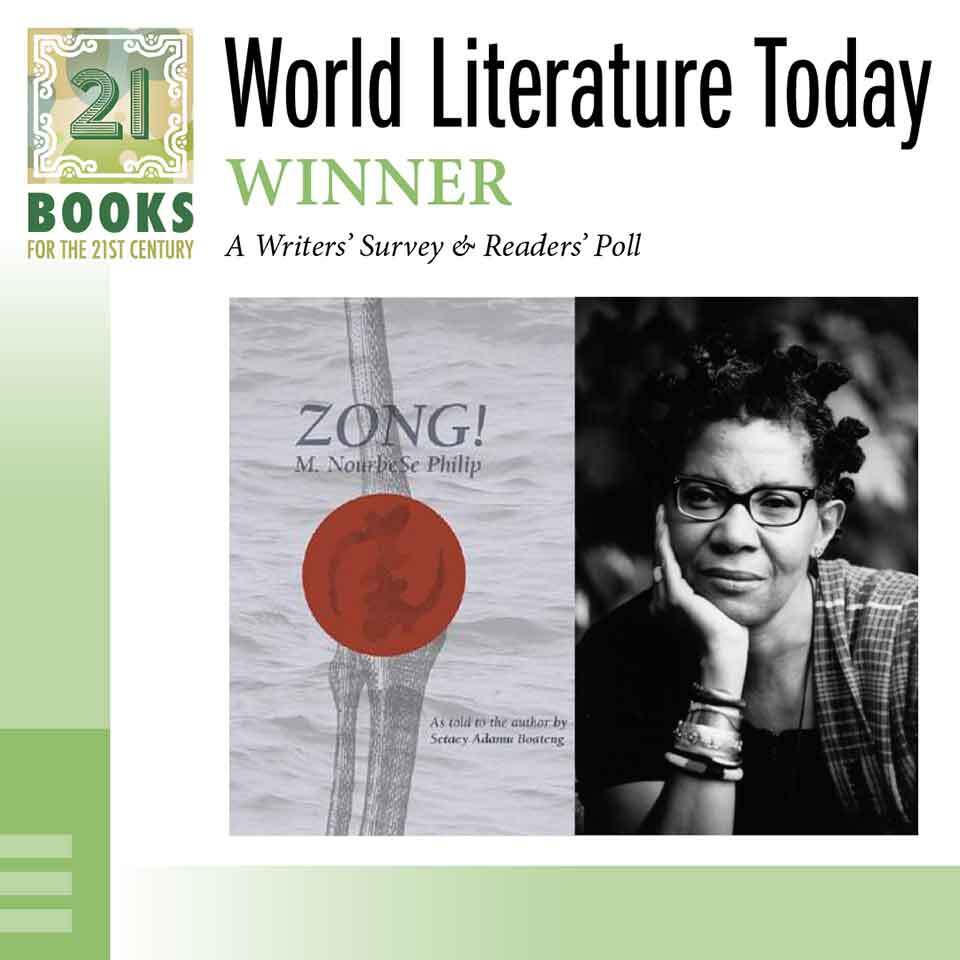

Earlier this spring, the editors of WLT invited twenty-one writers to nominate a single book, published since the year 2000, that has had a major influence on their own work, along with a brief statement explaining their choice. We published the longlist and then invited readers to vote on their favorites. M. NourbeSe Philip’s Zong! (Wesleyan University Press, 2008) not only received the most votes but was the runaway favorite. To commemorate the occasion, Philip and Metres struck up the following email exchange about the book.

Philip Metres: What does it mean for you to have Zong! recognized as such a pivotal work—one that has resonated with both readers and writers, and given birth to many other books interested in the parallel ongoing work of documentary poetics, archival unearthing, and attending to the trauma of those subject to the slave trade and other imperial and colonial depredations?

M. NourbeSe Philip: I do get a sense every so often of the work that Zong! has been doing. For instance, a professor shared with me that they were doing a job search and every job applicant had mentioned Zong! in their application. As writers and poets we all want our work to be read, noticed, and cherished, so when I become aware that others have found something of value in what I’ve written, it’s not so much that I’m happy, but I feel myself more settled—I can exhale. And this allows me to take another deep breath. That the work I’ve done has made some small contribution to expanding our understanding of what poetry can do in our ongoing attempts to correct the awful legacy of, and ongoing practices linked to, empire, race, class, gender, and sexuality is heartening; it shores me up when I grow tired and question whether we can actually extricate ourselves from our present position on the brink of environmental and human disaster.

Metres: You write extensively about the process of creating the work in “Notanda,” toward the end of Zong!, including a journey to Ghana to get a blessing to do this work. But I’d also love to know more about your relationship to Setaey Adamu Boateng—listed on the title page as “as told to the author by . . .”—and the process of collaborating with the ancestors while creating this work. Do you have advice for other writers about this practice?

Philip: I abdicated my role as author of Zong! in the sense we think of authorship, and I explore this in “Notanda.” Indeed, I describe myself as the unauthor of the work. I was following gut feelings when I felt the need to ask permission to bring these voices forward, and I would say that the most important aspect of the process of working with those energies, which are larger than us, is humility—a putting aside of the ego to be able to allow what needs to come through to manifest.

The names of the Ancestors on the cover of Zong! represent at least three different legacies, which it wouldn’t be appropriate to go into. Having said that, however, I should say that I didn’t see myself as collaborating with the Ancestors so much as listening to what seemed needed or necessary. These are all comments that run athwart how we talk about poetry today, although as poets we more often than not occupy that place in our thoughts, psyches, and emotions that as often remain unnamed, or when identified, as Keats attempted, bear names like “negative capability.” Living with uncertainty, accepting opacity, welcoming mystery, and, most importantly, humility or learning to put the ego out of commission (a difficult task for us as westerners so used to wielding the ego), these are all necessary for poets interested in this type of work.

In caring for this thing—language—that makes us beings who are human, in caring for the lowly comma or period, for the syllable or phoneme, for where they’re placed, we begin, I think—I hope—to care for others.

As poets, language is our medium—language used with great care—and in caring for language and the wonderfully difficult work it does, we learn to care for others, for the least among us; we care for their lives, filled with wonder, heartache, tragedy, and trauma. In caring for this thing—language—that makes us beings who are human, in caring for the lowly comma or period, for the syllable or phoneme, for where they’re placed, we begin, I think—I hope—to care for others. Care and attention—take care and pay attention is what I believe the craft of poetry to be about—paying attention and taking care. This would be my contribution to trying to find a way to work with that which might appear past, or to working with the Ancestors or howsoever we choose to describe this particular kind of work. For instance, as part of our annual performances of Zong!, I developed the Protocols of Care, which are essentially directions to help readers and participants feel cared for, at ease, and at home for the evening. The process also creates a space that allows for the presence of the Ancestors throughout the performance.

Metres: In our conversation for Synthesis magazine, you talk about the fact that in the Americas, we are living in forensic landscapes: “arenas where great crimes have been perpetrated, but which have never been acknowledged as crimes. Theft of the land from the Indigenous would constitute the original crime; theft and enslavement of African peoples would constitute the second and twinned crime. Could we argue—I want to argue—that since the commission of the crime, the perpetrators have been attempting through a variety of means, to erase and destroy the evidence of the crime—the continued survival of the very people who were trafficked—Africans.” Zong! is an example of how a poem might work to be part of truth processes that might unerase those crimes. How does your other work participate in this project of truth-recovery or marking the impossibility of truth-recovery? For you right now, what is the task of the poet and of poetry?

Philip: I enjoy writing essays—it’s an area in which I draw on my training in law to make argument. It’s an important activity for me because I don’t wish to make argument in poetry; I want to inhabit the contradictions: “english is my mother tongue / is my father tongue” (She Tries Her Tongue; Her Silence Softly Breaks). Essay writing also allows me space to explore ideas and issues in a more logical, left-brain way and, in a sense, to discharge that impulse and energy. Having said that, however, for the last several years I have been experimenting with bringing into essays some of the resources of poetry, such as repetition and fragmentation.

What you describe as the “impossibility of truth-recovery” aptly describes my view of the “project of truth-recovery,” particularly as it applies to poetry. It explains the refrain throughout “Notanda,” that this is a story that can’t be told yet must be told, and it can only be told by untelling or not-telling and all the inherent contradictions that accompany that statement.

This is a story that can’t be told yet must be told, and it can only be told by untelling or not-telling and all the inherent contradictions that accompany that statement.

Regarding the task of the poet and poetry—I think that each poet has to decide how s/he views their own work and the work they want it to do. For myself, the inestimable value of poetry lies in what I call its necessary uselessness. It is because poetry will not save us that we need it; it is because poetry cannot save us that it is more necessary than ever before. This may sound like a contradiction of what I’ve said in answer to your first question, in which I talk about enlarging the space of possibility for poetry, but I don’t think it is—at least no more than the realization and understanding that we are all end-stopped rather than run-on lines. We all come to an end, but that in no way prevents us from creating the marvelous—we continue to make art, music, poetry, startlingly beautiful buildings, bridges, electric cars, rockets, and novels in the face of what could be said to be the futility of life, which ends in death. Always.

Metres: Are there any questions that you would like to be asked and to answer?

Philip: Living with Zong! has been a learning practice, and I confess that sometimes I do feel the weight of it, which I try to carry lightly—not always successfully. A weight in the sense that I am presently facing two instances of people wanting to use the work but treating it as fungible. In one case the curator wanted to use pages of Zong! in a public outdoor art display but attempted to sanitize the text by not wanting to use any pages with the word “negro” in it because of current “increased sensitivity of the word negro.” In another case the work was translated unbeknownst to me, although they had acquired the rights from the publishers who failed to let me know. The result is a “translation” that completely destroys the conceptual and formal underpinnings of the work, resulting in a facsimile or a transcription rather than a translation that respects the work and the event it marks. Most importantly, in not allowing the words to breathe as they must, in ignoring or destroying the form, which is so integrally linked to breath and reparation, as limited as it might be, the “translation” fails to honor the dead and the Ancestors. This grieves me deeply.

People appear ineluctably drawn to the work yet often aren’t able to accept it on its own terms. Or, as happened a couple of years ago, they appropriate the ideas and the underlying theoretical and conceptual constructs without acknowledging the source—or, more importantly, the restorative work it is doing. As I say, it becomes weighty and demands a lot of energy to deal with these kinds of issues. I am trying to find a way to put in place a system to shore me up. Underlying it all is a kind of sedimented racism and sexism that is so much a part of the colonial—what I call the “we-own-the-world”—project, because these people are all well meaning and see themselves as wanting to help—to make a change. Too often, however, the same currents of white supremacy continue to swirl around these issues. As they say: Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.