If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I have spent most of my reading life reaching out for stories and poems which bloomed no easy answers of belonging. I wonder if it’s due to my own complicated identity as a queer brown person without a linear narrative around immigration and community—both heavy words that connote movement and endurance—or if it was my own seeking to make my own postcolonial state harmonize with others around me. As a reader, what most racialized Americans know intuitively is that there is a dearth of representation and voices that reflect diverse readers or the diversity of the North American continent. While white America still secretly holds the belief that to diversify literature means to compromise craft or quality—I’ve heard this whispered behind hands at readings and by people representing literary organizations—I believe that moving beyond white aesthetics to be uncanny in its ability to stretch American literature.

As I wrote Antiman, I was haunted by whether I could belong in this genre. I was inspired by books like Rolling the R’s by R. Zamora Linmark, Autobiography of My Hungers by Rigoberto González, and She of the Mountain by Vivek Shraya. These were all books of prose written by poets that explored the boundaries of form and genre: where does the poem end and the story begin—or was it the other way around? What moved me most was that these two genres offered different sensibilities for distillation of thought and emotion. Certainly, they allowed for complications of racial belonging, identity, and queernesses to perform their devasting craft moves through genre interactions. Other books that allowed me space to move through genre and narrative were Dear Current Occupant by Chelene Knight and The Atlas of Reds and Blues by Devi S. Laskar.

The books below are examples of nonfiction work and poetry collections that I see as important to the kind of searching that I constantly do. A question common to all of these books is their answers to the ubiquitous, micro-aggressive “where are you from?”. Here are complicated identities and belongings laid bare in recent books that provoke this central question: What is identity when it’s not white? How many belongings can we hold simultaneously?

Shame on Me: An Anatomy of Race and Belonging by Tessa McWatt

My cousin first recommended to me this memoir written by the Guyanese Canadian writer Tessa McWatt. In this nonfiction winner of the 2020 Trinidadian OMC Bocas Prize, the writer mires through the dehumanizing question of “what are you?” posed by white Canadians unfamiliar with the multiplicity of Caribbean-ness.

As a highlight of multiple belongings and complicated identities in diaspora, removed from the Guyanese context, McWatt structures her book around the physical characteristics to which most people ascribe to racial particularities. Chapters on the mouth, hair, lips, nose, serve as provocation for deeper diving into both the writer’s ethnic and racial history as well as the contemporary reading of her body in Canada. The beginning of the memoir opens with a prose poem in sections that imagines the lives of the writer’s foremothers: the African enslaved woman, the Indian indentured woman, the Indigenous ancestor, and more.

What I am drawn to in this book is the balance of personal narrative, research, and poetry by a writer from my parents’ own country. She writes in a language that I understand: she writes the Creole body that has always been in a state of motion. It’s not a common narrative, in fact, it’s exceptional. Anyone interested in complicated identities and deft prose should pick up this book.

Foreign Bodies by Kimiko Hahn

In her tenth full collection of poetry, Kimiko Hahn uses the notion of the foreign body (titled so aptly) to plumb the depths of belonging. Inspired by Dr. Chevalier Jackson’s exhibit of swallowed objects at the Mütter Museum, the speaker in these poems also considers the objects around her that launches the interrogation into the personal, interiority of a biracial daughter of a newly deceased father. The way the objects in the poems serve as provocation find the reader grappling through the associations that occur throughout this deft, precise work.

The formal elements of this text see creation and specificity that result in surprise and my own personal delight. One of the most moving aspects in this book (there are many to be clear) for me is the essay behind the poems called “Nitro: More on Japanese Poetics” where the poet distills the concept of kakekotoba, translated as “pivot-word” where there are multiple significations that the word points to in a kind of semantic ambiguity that provokes the reader into multiplicity. Consider even the title of the collection Foreign Bodies that signify both the swallowed object and the human body that is treated as though it does not belong. It’s easy to see why Hahn endures as a poet.

Curb by Divya Victor

I have been eagerly awaiting this collection from Victor since, after I read her previous book Kith, I recognized a poet who uses form and content to show the inconstancies of the “official” narrative that we read through media or colonial record. In Curb, Victor works her spell-craft as she implicates form in her speakers’ questioning violence against South Asian Americans in our heated and racist time. Some of the poems take the form of immigration documents, while some are free verse explorations of the particular South Asian people hunted by our nation in crisis.

She uses particular moments of violence against South Asians in the United States to wrest back control of the stories of victims of white supremacy such as Sureshbhai Patel, Balbir Singh Sodhi, Navrose Mody, Srinivas Kuchibhotla, and Sunando Sen. The violences are official: paperwork and through the police system, as well as the personal attacks of the white citizenry of the United States. All of these violences elucidate the implausibility of the South Asian American citizen and show how as a demographic we are both invisible and hyper-visible.

The curbs in this collection serve many purposes: to show suburban life, the peripheral nature of South Asian belonging and inclusion, and the structures (an infrastructures) of (white)power that threaten us every day. This is poetry as documentation, a testimony to the endurances of white supremacy.

All the Rage by Rosamond S. King

In her second collection of poems, poet Rosamond King explores the systemic racism that undergirds American society. The queer, US-based poet herself is of Caribbean and Continental African heritage, and to her craft, she brings a multiplicity of belongings from which the speaker implicates the reader in the virulent bigotry they encounter. The speaker warns the reader “I am not safe—and neither are you” as she deftly lays out lines that upset grammatical expectations of punctuation, reimagining punctuation as a stop and start of breath for the reader. By doing so, the particularities of “abattoir” glisten from the page and strike the reader with poems that sparkle with blood and rigorous interrogation.

Also emerging in this incisive, daring collection is awareness of survival in the time of the pandemic—specifically in Corona, Queens. Rosamond S. King proves again and again that she is a poet rooted in place with connections across seas and communities. The collection, inclusive of Trinidadian Creole English, hashtags, and outside textual references, ends with a section that takes the reader into moments of bodily and psychic joy. This book, as the title suggests is all the rage.

Southbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance and Social Change by Anjali Enjeti

This debut collection of twenty essays by Enjeti comes a couple of months before her novel The Parted Earth, proving her to be a virtuoso in two different genres: fiction and nonfiction. Southbound serves as a political travelogue of sorts, complete with various political awakenings, for a mixed-race South Asian woman who came of age in the American South.

The essays are well-researched and spin together threads of personal experience and culture into moving pieces that illustrate how identity can serve towards the end of coalition building for social change in our conservative-leaning, white supremacist country. The first essay that serves as an introduction is titled, “What Are You? Where Are You From?” asking the reader the questions she finds herself being asked. Enjeti implicates her own self in South Asian anti-Blackness and how white supremacy of the South has shaped her own understandings of electoral politics, feminism, and identity.

What moves me in this book is the honesty that the writer presents of her own experiences moving into accompliceship in smashing the systems of power that seek to disempower. The narrator survives and learn from an anti-immigrant Chattanooga, a father that denies racism as a survival strategy, the closely allied politics of both the United States and India, that resonate closely with my own experiences. Here the belongings Enjeti states are deeply Southern: South India and the American South—a complication of a daughter of immigrants hailing from Asia, Europe, and the Caribbean. This book can also serve as a guidebook to those who are looking to interrogate their own internalized biases and those who wonder what it means, emotionally and intellectually, to practice the fierce politics of radical justice.

Children of the Land by Marcelo Hernandez Castillo

In this tender memoir, poet Marcelo Hernandez Castillo traces his family’s complicated relationship with movement: consanguine connections, parentage, nation, and the intimacies as the young poet learns about himself through writing and exile. Hernandez Castillo’s hard relationship with his father’s deportation to Mexico haunts the young poet as he mediates his life as an undocumented DACA recipient in a country that makes his life difficult through its xenophobic laws and legislation. He learns how to hide himself, his status and his queerness, to survive.

What finally emerges from this memoir for me was a spirit that triumphs over ICE, over the people who would deny the poet humanity and dignity. This memoir by a poet uses language to cast and recast its multiple hauntings and belongings in a way that moves me as a reader to consider even more closely, how patterns of American racialization and land demarcation drains psychic energy. There are no easy answers here, but there is lyrical beauty and transcendence.

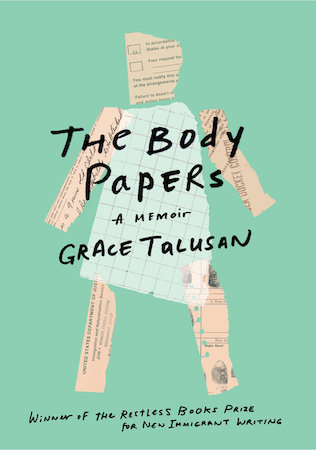

The Body Papers by Grace Talusan

Talusan’s award-winning debut memoir tells a complicated narrative of undocumented immigration to the United States from the Philippines. The writer as a young woman learns how to navigate the American school system despite the racism that seeks to cut her down. This is not the only complication of her narrative—a victim of sexual abuse by a family member causes her to ask questions of her own body.

After a cancer diagnosis, Talusan emerges into the new avatar of a storyteller—a gift of her familial inheritance that seeks to rescue the teller instead of the destructive violence she endured. The voice is arresting and devastating in its candor. In fact, Talusan’s memoir narrates the interior life of the writer as well in a seldom-told story of undocumented immigration to the United States from Asia.

Northern Light: Power, Land, and the Memory of Water by Kazim Ali

One of the queer South Asian writers whose books have been instrumental to me is Kazim Ali—and in particular, the mixed-genre book Silver Road that included poetry, fragment, and narrative. In his new book of nonfiction Northern Light, Ali takes a journey into discovering the physical and spiritual fallout of the hydroelectric dam project on the Nelson River in Manitoba, Canada that his father (one of 40 people at work on its engineering in the late 1970s) helped design.

Born in the United Kingdom to immigrants from Pakistan—originally from South India pre-1947, the date of India and Pakistan’s partition—Ali asks himself hard truths about the settler colonial project that sees him as complicit, his early forays into English literacy occurring in the temporary town of Jenpeg, 500 kilometers north of Winnipeg. He returns to this land after reading about the high suicide rates of the Pimicikamak people who reside in Cross Lake Treaty Lands.

Haunted by the question of his role in telling this story, this memoir asks how we as South Asian immigrants with tenuous and complicated belongings to the new national spaces of North America must reckon with the legacy of indigenous erasure from the land, sky, and most importantly waters. What does it mean to move beyond allyship with the earth and the People indigenous to it? In deeply poignant, researched, unsettling prose, Ali ends the book with a direct address to the reader, “Where does your electricity come from? Upon whose land does your home sit?”