If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

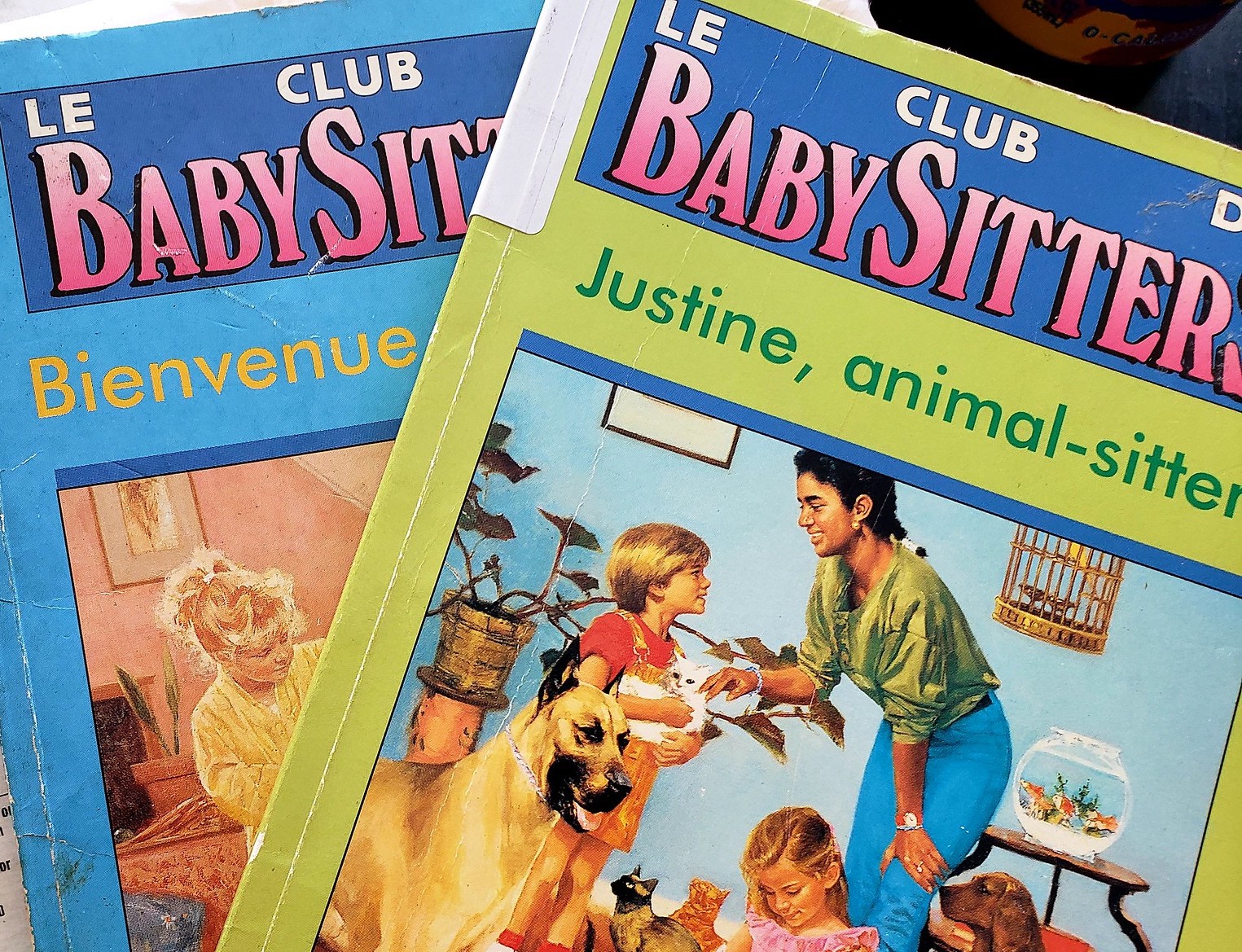

My parents’ basement is a home to many things, including (but not limited to) a slightly deflated exercise ball, a copy of Sound of Music on vinyl but no record player, and a stack of worn-out Baby-Sitters Club books. Today I’m here for the books. Neatly on top is the very first: The Baby-Sitters Club #1: Kristy’s Great Idea by Ann M. Martin. The worn-out cover features four girls lounging together and giggling against a faded yellow background. I wanted to be them then, and honestly, I want to be them now. The cover reads: “Four friends and babysitting—what could be more fun?”

The middle-grade series, first published in 1986, follows a group of friends and their local babysitting business, exploring themes of early adolescence, crushes, family, and more. And while the original series is understandably dated in many ways, the BSC continues to find its audience with newer generations via a live-action Netflix adaptation and re-released books with new cover art.

Even if it wasn’t your first choice to read as a kid, the BSC was undeniably everywhere. Their colorful spines lined the shelves of the bookstore’s children’s section, and they were a trusty staple at the local library. For many of us who read it and loved it, the series allowed us to pluck ourselves out of the mundanity of childhood and exist in the technicolor BSC universe where teen girls were always surrounded by friends, were financially independent, and navigated school and boys effortlessly. These girls were our role models, our entertainment, and our opportunities to reimagine our lives as the people we wanted to be.

Standing in my parents’ basement with a stack of BSC books in my hands, I’m suddenly aware that time has passed and I have aged since the last time I was here. I am reminded of how overwhelming childhood is, and how Martin’s series made aspects of it easier (and other aspects much more confusing.)

Editors, writers, and lifelong Baby-Sitters Club fans Marisa Crawford and Megan Milks seamlessly capture this chaos and beauty of childhood in the anthology We Are The Baby-Sitters Club: Essays and Artwork from Grown-Up Readers, a collection I didn’t know I needed until it was in front of me.

At its core, it is a love letter to the BSC reader. Featuring a foreword by Mara Wilson and essays by Myriam Gurba, Kristen Arnett, Yumi Sakugawa, and other writers, we are invited to celebrate the series’ everlasting impact for all of its strengths and weaknesses.

I chatted with Crawford and Milks over email about what we carry with us from childhood, what we learned from Ann M. Martin, and The Baby-Sitters Club as our first window into who we would ultimately become.

Anupa Otiv: Immediately upon finishing the collection, I dug for my old copies of the BSC and devoured them, as if I were 12 years old again. This anthology feels like returning to a former version of myself. When writing and editing, was it a challenge to speak for your younger selves? What was it like to be in that headspace again?

Marisa Crawford: I think that idea of speaking for or with your younger selves is so important. As an editor, working on this project was illuminating because it allowed me to see all these other experiences of young BSC readers, along with the adult writers they grew into. I think there’s something really powerful in revisiting the things you loved as a child—keeping that intense love that initially drew you to it, but now with a new, more adult understanding of the world that makes that initial relationship more complicated.

Each of the pieces in We Are the Baby-Sitters Club explores that relationship in different ways, and puts our adult selves in conversation with our younger selves. Jami Sailor, for example, didn’t read the BSC books as a kid but writes about discovering them as an adult when looking for media about characters who were, like Jami, diagnosed with diabetes as a pre-teen, and relating to Stacey’s experiences. And Chanté Griffin writes about feeling uncomfortable as a young reader with how the books address race in the stories about Jessi, and being able to now articulate those feelings as an adult. In my own piece, I did find it challenging to speak for my younger self—finding the right balance of honoring the young reader I was while also having a critical distance from that reading experience was harder than I would have imagined—but then again, of course, we shouldn’t be surprised that revisiting The Baby-Sitters Club forces us to look at our childhoods in new, sometimes difficult ways.

Megan Milks: Getting into the ‘younger self’ headspace you’re describing isn’t new for me—I’ve done a lot of writing that returns me to adolescence, but my confrontations with my younger selves are typically harsh and critical. One of the things I appreciated going back to the Baby-Sitters Club series as an adult is how evident are the affection and compassion Ann M. Martin has for the characters. Even as she gives them dignity, wisdom, and maturity, she also just lets them be kids—goofy and sensitive and figuring it all out. And of course, they’re kids looking after other kids—so they are in the business of practicing compassion and care.

AO: The idea of role-play comes up in several pieces, including Kristen Arnett’s opening essay, appropriately titled “Fun With Role-Play.” This essay perfectly captured the unbridled chaos of play in our youth and how the BSC storylines were merely a jumping-off point for our imaginations to run wild and mimic what we believed girlhood, adulthood, and everything in-between to be. What role does experimentation play in defining ourselves in our youth?

MM: I love this way of thinking about Kristen’s essay. And I love her use of second-person point of view in it—the remove adds a layer of voyeurism that is so perfect for the kind of doll play she’s describing, at the same time that it creates distance between her authorial and childhood self. That kind of play and experimentation—with dolls, and with writing/art—is crucial to trying out new possibilities for the self. And I think it is crucial for us as adults as well to maintain that sensibility in whatever forms we can.

AO: Something you touched on in your essay, Megan, was how the initial confusion or frustration we felt reading the series as children was actually a reflection on some undiscovered truth about our own identity. How do you feel the books we consume during our childhood shape our “adult” understanding of identity, gender, and sexuality, both positively and negatively?

Literary characters provide important models for who and how to be. The more possibilities that are modeled for us in childhood, the more possibilities we have for ourselves.

MM: It’s hard to isolate how we are shaped by the books we consume from the reasons we seek them out and connect with them. And we’re shaped by everything we consume, all the time. That said, it does seem clear that literary characters provide important models for who and how to be. The more possibilities that are modeled for us in childhood, the more possibilities we have for ourselves. I sometimes look back and lament that I never read the Weetzie Bat books as a kid—what new ways of being might this very queer world have unlocked? At the same time, I don’t know that I would have been able to respond to them that way then—I would have probably just thought they were weird.

AO: A common thread we see woven throughout the anthology is the effect that the diversity of the characters, or lack thereof, had on our experience with the books. How did Ann M. Martin’s diverse characters help people grappling with their identity in their youth? How did it potentially hurt them?

MC: I can’t speak for other readers of the books, but for me, I think that seeing diversity in the BSC family structures, and childhood illness represented in the books, helped normalize some of my own experiences as a kid. Building off what Megan said, seeing our own experiences reflected in books can be hugely affirming, whether we’re kids or adults, and the opposite experience can be isolating and painful.

Our anthology’s contributors’ experiences of course varied widely—we each experience books and all media in so many different ways. Frankie Thomas writes about Kristy as a proto-queer character and expresses frustration with Martin for suggesting that, in time, Kristy would be “ready” for a boyfriend. In Sue Ding’s essay about making her documentary The Claudia Kishi Club, she talks about Claudia serving as a model and inspiration for her and other Asian American artists. Jamie Broadnax critiques how the skin tone of Jessi Ramsey, the one African American BSC character, was often depicted as lighter than the book’s descriptions on book covers and other imagery, which Broadnax says sends a colorist message to young readers.

AO: Kelly Blewett put it beautifully in her essay, “Scripts of Girlhood: Handwriting and the Baby-Sitters Club”: “Reading as a child wasn’t just to pass the time or enjoy the plot. It was to figure out who we wanted to be.” This is so poignant and really describes the heavy lifting that books have done in defining our youth. What did you rediscover about yourselves in the process of rereading the series?

MC: I realized how much these books, while reading them as a kid, became a mirror for me. I was able to see myself in the characters, but I also projected what I needed to see onto them. Of course, that’s not an experience all readers get to enjoy as fluidly—as a white, cis girl, I had the privilege of seeing myself in the pages of these books with more ease and less complication than other readers may have experienced.

Revisiting the BSC books, but also especially through reading all the smart things our anthology’s contributors had to say, made me see even more clearly how the BSC influenced more parts of my life than I ever even realized—from remembering all the many outfits I modeled after Claudia (where would any of us be without her visionary fashion?!) to recognizing that duh, of course, religiously reading BSC books as a kid likely influenced my lifelong obsession with wanting a close-knit group of friends, or my learned understanding that I, as a young woman, should be nurturing, caring, and giving, even sometimes to a fault. Watching these characters create and work and grow together taught us so much.

MM: I rediscovered my dislike of the baby-sitting subplots. They took up space that could have gone to intra-BSC conflicts and intimate moments, as well as additional descriptions of Claudia’s outfits.

There’s something powerful in revisiting the things you loved as a child, with a new, adult understanding of the world that makes that initial relationship more complicated.

AO: Especially with children’s literature, there can be a disconnect between the intention of the author and what young readers actually take away from it. In my case, I can’t say I retained lifelong lessons about being a good friend from the BSC, but I do remember that Claudia Kishi once wore tights with clocks on them. What from the series continues to stick with you today and how is that different from what Ann M. Martin probably intended?

MM: I remember learning what molasses was from descriptions of Logan Bruno’s voice. And being always incredulous that the club had enough business—and time!—that they needed to meet Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. That is too much club time! But in terms of lifelong lessons (or existential concerns, as the case may be), I am still haunted by the idea, which is common in any group-based series, that in any given group dynamic, individual identities must sort themselves out and define themselves against each other with clear and consistent overlaps and divergences.

MC: Certain random phrases and language from the books—”needless to say,” “fork it over,” “oh my Lord,” etc., have stuck in my brain, forever associated with the BSC. And of course the ever-alluring concept of a “hollow book” for hiding junk food and other forbidden items. For a series that is so much about the power of friendship, the moments that stick with me most poignantly are pretty sad, lonely ones—Stacey secretly eating candy bars while dealing with her parents’ divorce, Claudia drinking tea with her grandmother Mimi on the cover of Claudia and the Sad Goodbye. I guess it speaks to the wide range of feelings these books were able to evoke, and the incredible detail in these stories.

How did the community aspect of this collection shape its direction and final form? What was your intent with the project and how did this group of unique perspectives make it what it is now?

MC: There’s something really special about realizing you’re in the company of a fellow Baby-Sitters Club fan. I’ll never forget how I felt stumbling upon Kim Hutt Mayhew’s blog What Claudia Wore online in the mid-2000s—I was in grad school and probably was supposed to be reading literary criticism about modernist poetry or something, but I felt this incredible rush of recognition to discover someone else who grew up reading the BSC books, still loved them, and was unapologetically indulging in that love in this really fun, smart, grown-up way. I felt that same recognition when I listened to Yodassa Williams’ storytelling performance about the BSC, and saw Siobhán Gallager’s Jaded Quitter’s Club comics, and Sue Ding’s Kickstarter for her film ClaudiaKishi Club.

For people who grew up reading The Baby-Sitters Club and still see value in these books, and still can’t let them go, I think it can make us feel like bad grown-ups or something sometimes. So there’s something comforting in knowing we’re not alone in this obsession, that yes, actually, of course, it makes perfect sense to give these texts that shaped so many young people’s lives the deep attention and celebration and critique that they deserve.

MM: I love what Marisa is saying about this guilt over being “bad grown-ups”—ha, exactly! But yeah, most of us who were part of that original generation of BSC readers grew up pre-internet, when fandoms were harder to access—I guess it’s no surprise that we are accessing them now, and that so many folks like Kim, Yodassa, Siobhán, and Sue have been creating fan content as adults, and inviting that community (or club!) dimension that we didn’t get then. Another contributor, Logan Hughes, writes about participating in the BSC fan fiction community as a queer and trans adult. Marisa and I were definitely interested in creating a sense of community with the book—and we hope the title We Are the Baby-Sitters Club reflects that.

Like any fan-based community, our love and investment come with critique—disappointment in what the series got wrong, ideas for what it could have done better. As we were developing the anthology, we knew from the start that we wanted to combine enthusiasm for the series and its legacy with more critical perspectives—and we made that clear in our call for pitches. We also prioritized bringing together a diversity of voices and perspectives, and so combined solicitations with an open call that named a number of topics, like the series’ handling of disability, for example, and its lack of body diversity, that we knew we wanted the book to cover.