If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

When I drove to my high school girlfriend’s house to have sex with her for the first time, I still did not know what two girls were supposed to do in bed. I wasn’t so much curious about sex as resigned to it; my girlfriend was the one who had insisted sex was “the closest you could get to someone,” and that every couple in love did it—none of which told me what exactly it was or how it would feel. I kept a journal that summer, and that night, I wrote a frantic, stream-of-consciousness account of what sex that afternoon had been like: the washed-out alienness of my girlfriend’s face against her pale, naked torso; the clunk of a cassette tape flipping and flipping again as I worked up the will to do anything more than lie there with our shared sweat sticking my skin to hers.

Lesbian sex, I learned over the next four months, was cunnilingus and fingering, then switching places for more cunnilingus and fingering, then holding each other and rhapsodizing about how beautiful our cunnilingus and fingering had been. Lesbian sex was sobbing beforehand because I didn’t want to do it, and my girlfriend sobbing because we couldn’t just stop. It was crying myself out, then being too numb to care what we did next, so why not give her what she wanted? Lesbian sex was the existential loneliness of my girlfriend’s face disappearing between my thighs, was staring at the X-Files posters on her wall and begging my body not to betray me with sound or scent or motion, was mentally tallying the time I’d been touching her and watching her face for any sign I’d be allowed to stop. But in my journal, after that first night, lesbian sex was simply platitudes: we had sex, we had tender sex, we had loving sex—as if the story of what we were doing erased its reality.

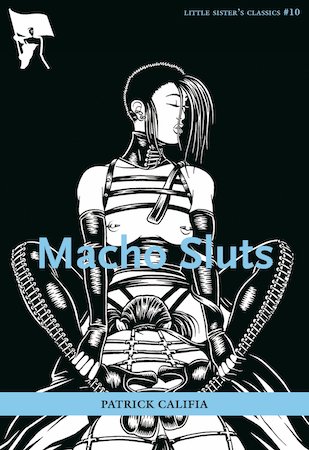

After years of trying to find words for what I’d experienced, a friend lent me a copy of Patrick Califia’s Macho Sluts. Published in 1988, Macho Sluts was a collection of character-driven pornographic short stories and an infamous salvo in the war between feminists who proudly practiced BDSM and those who believed that egalitarian, reciprocal sex was the only acceptable erotic act for lesbians or feminists. (Califia, who has since transitioned to male, wrote at the time from within the lesbian community.) My friend had found the book formative in their journey as a BDSM top and thought perhaps I too might see some of my nascent desires reflected in “Jessie,” where a bottom in leather restraints picks up an aloof rock star at a women’s music venue, or “The Calyx of Isis,” where the owner of a fantastical women’s sex club in San Francisco orchestrates a veritable feeding frenzy of an SM scene. Where I saw myself, though, was in the book’s coda, a modest, nasty skewering called “A Dash of Vanilla.”

“Vanilla” is the BDSM community’s term for normative sex acts—the kinds Califia’s detractors would have considered virtuous—and indeed this final story in the collection describes a sex act with no negotiated power exchange or pain play. What we see instead is a protracted sex scene that reads like a hostage situation, a grueling, claustrophobic, moment-by-moment account of the narrator performing cunnilingus on her long-time lover, an act that must end either in the lover’s orgasm or the narrator’s failure.

Lesbian sex was sobbing beforehand because I didn’t want to do it, and my girlfriend sobbing because we couldn’t just stop.

The narrator’s distress, physical pain, and aloneness are palpable throughout. “You’ve told me to stay in one place and do the same thing until you come,” the narrator says early on in the encounter. Adding to the loneliness of the piece, the narration addresses the partner in second person in a constant internal monologue, though outside the narrator’s head, the lovers barely speak. “You’ve also told me that you sometimes need to move around to put my tongue in the right place…You never seem to be able to tell me what’s going on while it’s happening, so I have to guess, and half of the time I’m right and half of the time I’m wrong.”

By the middle of the encounter, the narrator’s neck aches, her hands are numb, her mouth is dry, and there is sweat in her eyes. “I get progressively more depressed and full of despair,” the narrator tells her lover silently, “because nothing seems to be happening or changing or getting better with your body and its physical response.” Later, her despair turns outward: “I am angry with you because you are taking so long, angry because you leave me alone down here, with no idea what is going on with you, if you are enjoying it or not…”

This feeling of disempowerment, of profound isolation in a moment that is meant to be intimate, is gut-wrenchingly familiar. So too is the double-bind: move but don’t move; please me, but I can’t tell you how. When my high school girlfriend insisted that two people in love couldn’t just stop having sex, I would second-guess my own refusal, and then I too would find myself between a lover’s legs with no roadmap. With the one thing I wanted—to stop having sex altogether—off the table, every imaginable next step seemed as meaningless and yet as unavoidable as the next.

I say this now, but at the time, I did not understand that I was miserable. The stories of what sex was supposed to be obscured how it actually felt. When I sobbed about not wanting to have sex, I was lamenting my own failure: sex was a beautiful, magical thing that two people in love did together. What puritanical, anti-feminist dogma must I have internalized that my impulse was to avoid it?

I say this now, but at the time, I did not understand that I was miserable. The stories of what sex was supposed to be obscured how it actually felt.

Nobody around me saw how miserable I was either. My girlfriend and I were two cis white femme teenage girls who walked around our liberal college town holding hands. Teachers, friends’ parents, the local queer youth organization’s board of which my girlfriend and I were token members, all seemed either to think we were adorable or to think they should think we were adorable. It was the late 1990s, love was love; if I couldn’t make it through calculus class or college counseling without bursting into tears, then surely the problem was college, or calculus, and not what happened privately, after school, with someone who just happened to be another girl.

The narrator in “Vanilla” also tells herself stories about how sex feels. “I’m….glad you insist that I get you off,” she says, early on, “insist that I keep trying and work to get better at it.” But in the context of the pain and distress that come later, this assertion reads to me like those hollow lines from my high school journal: less a true reflection of the narrator’s attitude than an attempt to persuade herself that what follows is wanted.

It does not, it seems, read that way to critics. Contemporary reviewers of Macho Sluts tend to focus on the explicit BDSM stories that make up the bulk of the book, mentioning “Vanilla” only as an afterthought. The mention in the Bay Area Reporter, Califia’s local queer newspaper, takes the story at face value: “‘A Dash of Vanilla’ is just that.” The one in lesbian erotica magazine On Our Backs comes closer: “This story didn’t so much pass a wet test as made my jaws ache,” the reviewers write, but then add “but that’s just as much a part of lesbian sex as getting off”— as if they see the story’s failure to arouse not as deliberate commentary, but as the forgivable misstep of a self-avowed pervert attempting to cater to the lesbian mainstream.

What made it so hard for those first queer reviewers to see the misery in “A Dash of Vanilla”? I imagine they were seduced—particularly after the rest of the book’s hoods and gags, canings and restraints, bottoms ceding power to tops—by preconceptions of what vanilla sex is supposed to be.

It’s the kind of harm I felt alone in for years, the kind that comes from focusing on the story of what sex is supposed to be without examining how it actually feels.

The sex in “A Dash of Vanilla” does have the trappings of gentleness and egalitarianism. Neither partner seeks out pain, though the narrator, with her stinging eyes and aching neck, experiences it unacknowledged. Both partners have orgasms, though the narrator’s, which happen uninvited as she tries to give her lover pleasure, add to her sense of failure. Both partners are women, both cisgender, both racially unmarked in a way that reads as white in context, and the violence of cis white women is notoriously slippery—easy to overlook, or to pin on someone else.

More disorientingly, the violence in “Vanilla” isn’t straightforwardly about a victim and a perpetrator. The sex is unpleasant without being exactly assault; there is coercion, but it is unclear how much comes from the lover directly and how much from the widespread belief that bringing one’s partner to orgasm is the only way to make a sexual encounter a success. If there is a guilty party here, it is not so much the lover as the institution of vanilla sex.

It is tricky too to assign blame for what happened to me in high school. There were moments where my girlfriend clearly pushed and crossed boundaries, but the stories she used to manipulate me—sex is beautiful and intimate; you can’t just stop—were not her invention, and I think she genuinely believed them.

But the point of focusing on the violence is not so much to identify and remove a perpetrator, it’s to identify and acknowledge a particular kind of harm. It’s the kind of harm I felt alone in for years, the kind that comes from focusing on the story of what sex is supposed to be without examining how it actually feels. The kind that comes from telling very narrow stories about what eroticism is rather than acknowledge its breadth and potential.

I am, it turns out, both gray asexual and kinky. I don’t have much desire for sex itself, which helps explain why I felt so lost in it as a teenager. The kinds of physical intimacy to which I am drawn involve power and pain—activities that almost never appear in stories of what people do when they love each other. I do not know if the cultural stories about sex serve anyone (though the reviewers willing to concede being unaroused and in mouth pain as a regular feature of lesbian sex makes me suspect not), but they were certainly never going to serve me.

What pain could I have avoided if I’d heard any message from anywhere that you could love someone and still categorically not want to have sex with them?

Those stories didn’t serve Califia either, who writes in the introduction to Macho Sluts: “Our culture insists on sexual uniformity and does not acknowledge any neutral differences—only crimes, sins, diseases, and mistakes.” What pain could I have avoided if I’d heard any message from anywhere that you could love someone and still categorically not want to have sex with them? What joy, confidence, and connection with my own body could I have felt if—free from pressure to have sex I didn’t want—I had had the space to imagine what acts might actually bring intimacy and pleasure?

“A Dash of Vanilla”’s sexual encounter ends with a troubling moment. The lover’s elusive orgasm finally complete, the narrator begins to digitally penetrate her lover, despite her lover clearly telling her not to. “I say, ‘Why? Why not? I want it. You can’t stop me. Give it to me.’ Then I fuck you.” This moment, more unambiguously than anything the lover inflicts on the narrator, reads as a sexual assault.

Maybe the unwanted fucking is reciprocation: after being used by her lover in ways that feel at once pleasurable and awful, the narrator turns the tables. Maybe it is revenge—a trapped animal lunging at her captor. Or maybe it is a wounded answer to those who refuse to see violence when it is couched in gentleness at the hands of women. If the lover’s womanhood enables her to hurt the narrator and get away with it, then maybe crude misogynist violence against her is a satisfying cheap shot. Whatever it is, it undermines some of what makes the story special to me. I read “A Dash of Vanilla” as an exploration of the psychological harm wrought by normative sexual expectations. A moment where the narrator violates her lover, with no real indication of the moment’s impact on the lover, feels out of place. It gives me pause when recommending this story, though I do still recommend it to anyone who can stomach this final, unsettling act.

We tell ourselves so many stories about what sex is and what it is supposed to be. The anti-pornography feminists in resistance to whom Califia wrote Macho Sluts insisted that BDSM was violent, dangerous, misogyny incarnate, while rarely applying the same scrutiny to vanilla lesbian sex. The good ’90s liberals around whom I came of age claimed that sex was a beautiful expression of love but never once suggested I notice how my body felt imagining or doing it. I have so often felt alone, even within queer communities, in a reality that does not match these stories.

Compassionate depictions of experiencing sexual assault are, thankfully, somewhat common these days, but I do not see myself in them. To find a piece of writing that gets at the kind of ambiguous sexual misery I felt alone in—particularly one involving queer partners, particularly one that implicates the institution of vanilla sex as a root cause—is an astonishing gift. It has been more than thirty years since Macho Sluts’ publication and more than ten since I first read “A Dash of Vanilla.” Nothing I’ve read before or since has come as close to reflecting lesbian sex as I knew it.