If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

I believed the stories of the Bible more than I believed anything else for the majority of my life. I quoted scripture to make decisions, considered parables when confused, consumed evangelical Christianity in a kind of keg stand of my own righteousness. But what I learned when I lost my faith, slowly and then all at once, is that evangelical Christianity isn’t a religion—it’s a culture. Losing your faith is both an existential drought and a culture shock.

I lost the most influential book in my life the minute I lost my faith. There isn’t much scripture to tell you how to stop believing. And it was hard for me to find stories in general that I needed to help understand and survive my experience. There were books about breakups and friend fights and college decisions; novels about worrying about your future and your family and your dreams. But there weren’t very many novels about wondering whether everything you’d ever believed was a lie. There were even fewer novels that were able to untangle the harm the white evangelical church has done and also the love it can provide.

When I started working on my debut novel God Spare the Girls, I was processing my own loss of faith, and trying to understand how something that had been so fundamental to my development as a person could have also been so harmful. The story is tightly focused on Caroline Nolan, the daughter of a megachurch evangelical pastor, who is forced to question everything she’s ever known when she discovers her father’s secret. The drama that unfolds centers on her church, her community, and her family, but it’s also about the internal drama of questioning and how painful that can be.

No work, though, is ever really the first. As I wrote, I found other books about Christianity, books about losing faith, books about seeing the place that you’ve known your whole life after the scales have fallen from your eyes. These 7 books made me feel the way I hope my book can make someone feel: less alone.

Revival Season by Monica West

Monica West’s story is about a young revival circuit preacher’s daughter who is forced to question the nature of miracles and the power of God. Though we did not know each other when we were writing our books, all of the same questions are in each of our novels: how do you question truth? How do you recognize power? What do you do when something you thought was good turns out to be bad? The plots aren’t similar, and the places our protagonists end up are drastically different, but reading Revival Season made me realize just how universal these questions are, and just how meaningful.

The Mothers by Brit Bennett

Brit Bennett is a beautiful writer and her prose is mesmerizing, but what I loved most about her debut novel The Mothers is its contradictions. The story is about Nadia returning to the place where she grew up and being forced to confront her past: including her relationship with the pastor’s son. Bennett lays bare the biases of this California church and the effects of a tight-knit community that gossips. She doesn’t shy away from describing the shame many young women in the church feel.

The Abstinence Teacher by Tom Perrotta

The Tabernacle of the Gospel Truth—the fundamentalist church in Tom Perotta’s The Abstinence Teacher—is a bit more extreme than modern-day evangelicalism, but their beliefs on sex are the same. This story of a high-school teacher forced to teach a Christian sex-ed curriculum is way funnier than it has any business being. Its central pastor is warm and loving, but holds strict doctrinal beliefs, and Perrotta isn’t afraid to make good-natured jokes about the culture of Christianity.

Kristin Lavransdatter by Sigrid Undset

This early 20th-century Norweigian trilogy is a family saga about a young girl named Kristin Lavransdatter living in the 14th-century. Kristin is sent to a nunnery, and though her faith isn’t evangelical, much of the books focus on her questions about God’s nature and his wrath. “I didn’t realize then that the consequence of sin is that you have to trample on other people,” she says. The book is full of as many proverbs as the Bible (“man proposes, God disposes”), and treats the faith of this young girl as just as valid as the knowledgeable priests she interacts with.

Transcendent Kingdom by Yaa Gyasi

Gifty, a talented 28-year-old scientist, must deal with her faithful mother’s second major depressive episode. Gyasi does a marvelous job of explaining the tension between heathen child and religious parent, and of laying out how unaware of our own trauma we can be.

Wise Blood by Flannery O’Connor

Flannery O’Connor’s first novel Wise Blood is one of the only books I’ve ever seen that displays the pipeline from extremely religious evangelical to extremely pronounced atheist. Her protagonist Hazel Motes, grew up with doubts about his faith and after the war begins to preach the gospel of his lost faith. What I love about this book is that O’Connor portrays Motes with such sympathy, allows him to be terrible to people around him without ever demonizing him, and shows that zealousness isn’t reserved for Christianity alone.

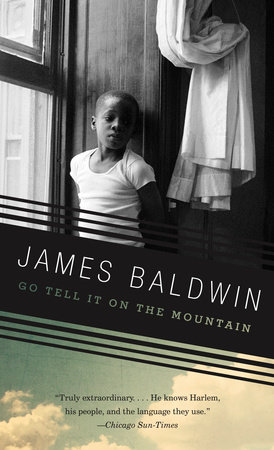

Go Tell it On the Mountain by James Baldwin

James Baldwin’s novel Go Tell it On the Mountain is one of my favorite stories about preacher’s kids. Baldwin’s protagonist John Grimes is desperate not to be like his father, the best pentecostal preacher in Harlem. The novel is littered with Biblical allusions and stories, and Baldwin is forthright with the cause of Grimes’s loss of faith—his disillusionment with his father:

“John’s heart was hardened against the Lord. His father was God’s minister, the ambassador of the King of Heaven, and John could not bow before the throne of grace without first kneeling to his father.”