If you enjoy reading Electric Literature, join our mailing list! We’ll send you the best of EL each week, and you’ll be the first to know about upcoming submissions periods and virtual events.

When I first meet a writer on the page, I pose a simple question: What don’t you ask permission for? In Yiyun Li’s case, the answer is her freedom. Individualism might seem inevitable for a woman who was born in China and whose early work responds to authoritarianism, but—reading Li—one senses that these are among myriad forces that have shaped such insistence. Dissent, evasion, what a person does when they are cornered, how a person refuses to be known and thus never contained—these have been Li’s obsessions over the last 20 years.

Li was on the verge of becoming a doctor at 22, having immigrated to study immunology at the University of Iowa, when she decided instead to become a writer. In her nonfiction, she is in conversation with great thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard—though this feels true of her fiction as well. Yet beneath the intellectual grappling, there is great warmth.

Li’s entire body of work—beginning in 2005 with her award-winning collection A Thousand Years of Good Prayers and followed by four novels and one very un-memoir memoir—might be understood as a dialogue with no plans for a last word. Li might be saying to us, “I am as mystified as all of you.” Not that she will be satisfied in this. Li continues to ask the questions most of us in our waking lives shy away from. This is true, especially of her recent work. Dear Friend, From My Life I Write to You in Your Life relays Li’s experience with suicidal depression and attempted suicide over a two-year period. Where Reasons End, her third novel, written over three months, occurs between a mother and her dead son. Li lost her own son, Vincent, to suicide in 2017. Must I Go is at its heart an accounting of grief and what remains unspoken.

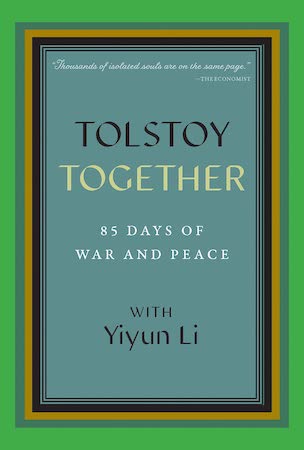

Any chance I get, I seek Li out as a teacher and master. Thousands do. At the start of the pandemic, when we were all befuddled, Li hosted a virtual book club on War And Peace through A Public Space. (Readers can join her this fall for the encore.) The experience, like all of Li’s writing, serves as a reminder that literature is a place where we meet, and if it cannot give solace, it can offer communion.

Annie Liontas: Last year during pandemic, people from around the world joined you and A Public Space to read the epic novel War and Peace at 15 pages a day, and then tweeted about it. In the words of The Economist, “Thousands of isolated souls are on the same page.” What inspired you to make that offering?

Yiyun Li: Part of the reason I chose War and Peace: even at the most difficult times of my life, I could read it 30 minutes a day. I knew from my experience that a solid structure always helps. That’s the most important thing, you just have to move from one day to the next.

Certainly, Tolstoy would not have imagined me as his reader. He is flawed, as a writer, as a human being. I’ve been looking at his diaries—he got addicted to gambling, he lost all the money. But even as a flawed man, he could produce such a body of work. Let me put it this way: if I don’t judge him, I learn so much.

At the beginning of the pandemic, I was thinking people would have a hard time, not knowing what we were going into. I actually imagined maybe ten, twenty readers would read with me. War and Peace was a big, big book that could move the days forward. What I learned for myself—having hundreds of readers commenting, all of a sudden I can see my own blind spots. I can see my own judgmental opinions about characters, with other readers coming from other angles—it’s just lovely! It has taught me how people read the same text differently, but every reading is legitimate.

AL: Many readers discovered your fiction through The New Yorker, where you’ve been publishing since 2014. I assign “A Sheltered Woman” each semester, asking students to map one element (they graph Auntie Mei’s moods, what remains unsaid, “Where is baby?”). Like Auntie Mei, most of your characters resist confinement, perhaps because they cannot bear to be known. How do you get close to a character who is as intent on her own freedom as you are on yours?

We do want to be known, but also we’re risking being misunderstood or misread. There is always that dichotomy, both wanting to be seen and also wanting to be invisible.

YYL: I do believe characters are like us. We do want to be known, but also we’re risking being misunderstood, or misread, or misinterpreted. There is always that dichotomy: both wanting to be known, wanting to be seen, and also wanting not to be known and to be invisible. You’re right, all of my characters share that.

That is the most fascinating thing about being a writer. My whole struggle with myself is no longer there. That tension between me and my characters—I push them, they push back—that’s the fun. It’s all about getting to know them better, being pushed away, coming back day after day. I can never say I know them a hundred percent, I just know them a little better after I finish a story.

AL: So how do you build intimacy with a character who keeps secrets? And once you’ve finished—once you are no longer looking in on your characters day after day—how do you carry your characters?

YYL: I think the intimacy—it’s almost a competition of who can be more transparent. Characters are never transparent enough with us. But if I am transparent—which means I am nowhere, I am immersed completely in their lives—I feel they let their guard down at moments. We get attached to those moments when our characters are less opaque. Those moments, when they’re vulnerable or when they’re cracking a little, you squeeze yourselves into their lives a little better. Characters are like us, they don’t want to be known, but they have this desire, and sometimes the most difficult thing is they don’t want to admit—we don’t want to admit—that we’re grateful for being known. But we are.

I don’t think I can carry all the characters. They go back to their lives. Sometimes I run into them in real life, and I think, Oh, I have written you before. How do I carry my characters? I think sometimes maybe they carry me!

AL: Your family lived through three regimes in China, two world wars, two civil wars, famine, and revolution. When you were six, you were brought to a ceremony for an execution and recall seeing one of the prisoners, a woman, you still think of her hair. How did such images and stories—even the stories that perhaps went untold but could be felt—imprint on you?

YYL: Those memories are about China, but they’re also about being a child and not knowing the world. To me, memory is about going back and making sense of what you’ve absorbed. As children, we don’t know what’s happening to us. For instance, if you’re six and you’re watching these things, there is no continuous narrative. There are only glimpses or fragments of images; someone said something to you that you can’t figure out.

Writing is about making the most sense out of the things that make no sense. All sorts of things—injustice, cruelties. It’s good to come back as an adult, as a writer, to sort those out. It doesn’t make the memory easier, but it brings the picture into sharper focus.

AL: You write in English instead of Chinese. You’ve talked about this conscious decision as both liberation and “a kind of suicide.” How does writing in English help you reinvent or reclaim?

YYL: It’s about making every word a word. I don’t know if you have that experience with English, but I have that experience because I grew up with Chinese. Every time I write, I want to make sure every word carries meaning. Even cliches to other people are not cliches to me. I want to know the origins of the expression. People say water under the bridge. What bridge? What water?

I do think that fascination with language is twofold. One, I want to express things as precisely as possible. And two, it’s the awareness that I will never get it right. I can get close, but I can never get every word to align perfectly. I cannot get the sentence to say exactly what I mean. I like that tension between myself and the language. I think that’s everyday struggle, but it’s also everyday joy.

AL: Have you always felt that way? Or is this something you discovered along the way?

YYL: Yes—I would say it has changed. As a new person to the language, I didn’t even know my limit—I felt limitless. Which is an illusion, right? I was actually most limited when I first started. But I have written for twenty years, and the longer one writes the more one questions oneself. Every single word I put down, I look at it again. Language is no longer just a tool to tell the story, it’s part of the storytelling.

AL: For much of your career, you’ve resisted being seen as an autobiographical writer. In recent years, you’ve called that impulse false. What did that lie grant you when it felt like a truth?

Writing is about making the most sense out of the things that make no sense: injustice, cruelties.

YYL: For the longest time, I refused to be called autobiographical. Part of that instinct was to hide. This was a major motivation for me when I became a writer, which doesn’t make sense because when you write, you put your work out there—you put yourself out there for people to judge.

The first phase of my career was to find a good hiding place in the characters. Oftentimes, the characters were totally different from me—older man, older women. But you can only hide for so long! It’s such a good lesson. You cannot hide forever. Hiding becomes a limitation to the work. At some point, I have to say, This is me, and this character has my experience.

AL: Language seems maybe the worst place to try to hide, like a forest without any trees!

YYL: Isn’t that funny? We’re trying to bare our souls while hiding!

AL: I’m thinking of Lillia in your recent novel Must I Go. She is as much in conversation with those who have died as with those she will leave behind—most poignantly her daughter Lucy, who she lost to suicide. Lillia tells us that words are of no help to memory. “I keep people,” she says. “Not out of greediness…I keep people because I like living among them. They don’t always know that.”

How do you think of keeping? Is writing Lucy a way to keep Lucy alive?

YYL: Lillia has a lot of blind spots. She’s like one of her ancestors running to the Gold Rush, not knowing if there is a bear or a rattlesnake, just rushing forward. What makes life interesting is you can walk straight ahead but all those things that grab onto your shirt, your hair—they’re always going to be there. The other part of her is she does not allow herself to show she is vulnerable. She is grieving for this child all her life. The posthumous letters to her lover are really about grieving the daughter she doesn’t know well.

Keeping people…that is such a good question. Maybe we should just write a story called “Keeping Lucy!” That’s all we can do for characters, keep them alive for a moment. It’s the same as a mother with a dead child. That urge—it’s why we love writing. The book is about record keeping, all these journals and diaries—and in life, we keep stuff, objects, pictures, whatever. But they’re all just approximations of keeping someone. You can never keep that person. We get as close as we can, keep a little bit, so not everything slips away.

AL: I understand that you interrupted writing this book to write Where Reasons End. You talk about the novel after your son’s death as the funniest book you’ve written about the saddest thing in your life. What did it give you, even as it only let you keep so much?

[The online book club] has taught me how people read the same text differently, but every reading is legitimate.

YYL: I was in the middle of writing Must I Go when Vincent died. I did wonder if I should give up the novel. I think my instinct was that I could not write it. It was an odd matching of Lillia’s life and mine. My mind got a little foggy, I couldn’t tell the difference between us. At that time, Where Reasons End felt like a book that needed to be written. I spent maybe three months on it. I remember talking to my agent. I said, This is a book that is never going to end. There are 16 parts, but I could write 60. She said, You’re right, you just have to decide when to finish it. The book ends here, but life does not end here. Ten years from now, I will probably still be writing that book. Afterwards, I realized of course I can write Must I Go. After Where Reasons End, it became obvious that Lillia was Lillia and I am me.

AL: What did it mean to you re-issue of W-3, Bette Howland’s 1974 memoir?

YYL: At the time of her hospitalization, Bette Howland was the mother of two young boys, and I’ve often felt an uncanny connection to her, as I had my own suicidal struggle and hospitalizations when my children were young. The experience she had written in W-3 felt close to mine—being a mother to young children and being a daughter to a complicated mother, finding time/space/energy/sanity to write, being on a mental ward with many people suffering for different reasons. What she wrote in that book, as I mentioned in the introduction, is something I couldn’t imagine myself writing, and yet she did. The reissue of W-3 means a lot to me, and I believe to many women artists who have struggled with similar issues.

AL: You’ve said that it’s impossible to keep a novel clean while writing it, that you have to make a mess before you can clean it up. What advice about making messes can you give?

YYL: War and Peace is a big mess! Hundreds of characters. But one thing that is very clear is the scaffolding—war, peace—a very arbitrary, solid structure. When I say make a mess, I don’t mean to make things complicated, rather to make the work complex, which comes from characters, emotional depth, intellectual depth. The best musicians don’t make complicated music, they make complex music.

YYL: Is there anything about your work you’d like us to know, 20 years out?

AL: I am less impatient. Patience is always the best in writing. All of a sudden, I realize there are more stories to write! There are more books to write!